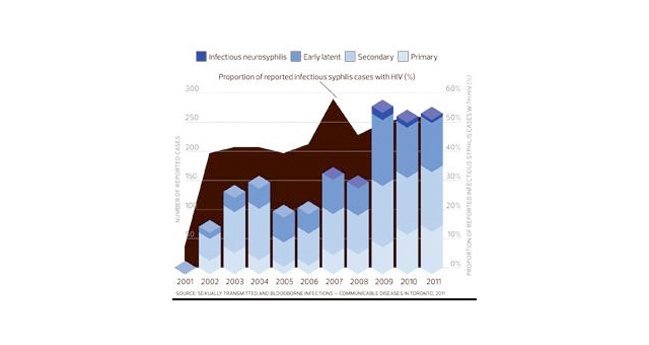

Incidence of HIV and infectious syphilis co-infections by year, Toronto, 2001-2011. Credit: Xtra file photo

Marco Posadas runs TowelTalk, a bathhouse counselling program in Toronto. Credit: Andrea Houston

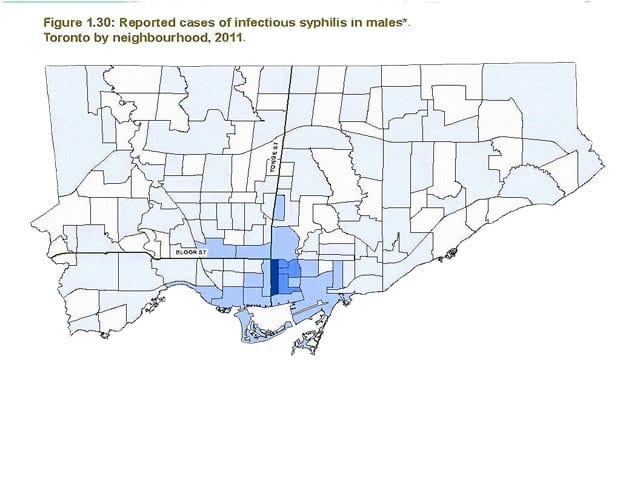

Reported cases of infectious syphilis in males, Toronto by neighbourhood, 2011. Credit: Xtra staff

John Maxwell says HIV criminalization is one reason STIs are on the rise. Credit: Adam Coish

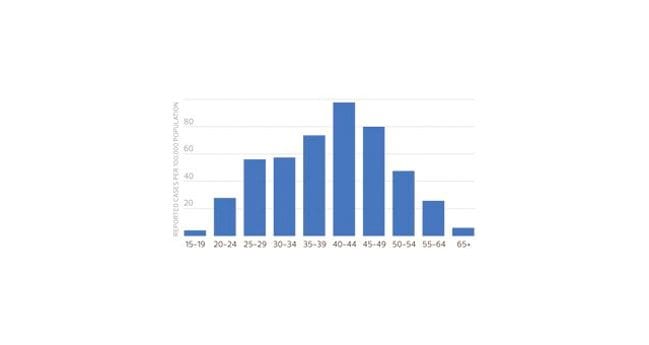

Incidence of infectious syphilis by age group and sex, Toronto, 2011. Credit: Xtra file photo

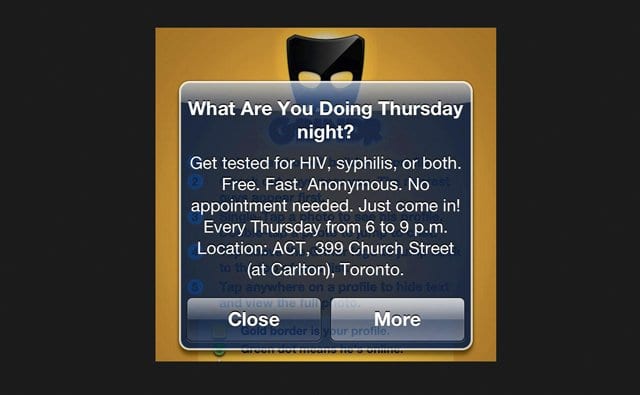

Advert Credit: ACT

What do you do when someone you’ve hooked up with calls to tell you he’s got syphilis? Do you a) get high and forget about it? b) Get angry at your playmate for potentially giving it to you? c) Contact everyone you should to warn them? d) Recognize how hard it must be to make such a call, respond with compassion, help the caller to feel better and then immediately get tested?

In Ontario, syphilis is a gay man’s disease that is currently spreading like the common cold, with a 25-percent reinfection rate. Untreated syphilis becomes secondary syphilis in six to 12 weeks, and for those who are HIV-positive, tertiary complications — which can include paralysis and organ failure — can occur in one to two years.

And, notes Robert Remis, an epidemiologist at the University of Toronto’s Dalla Lana School of Public Health, the majority of men who have syphilis in Ontario are living with HIV — “roughly five-fold higher than among negative men.”

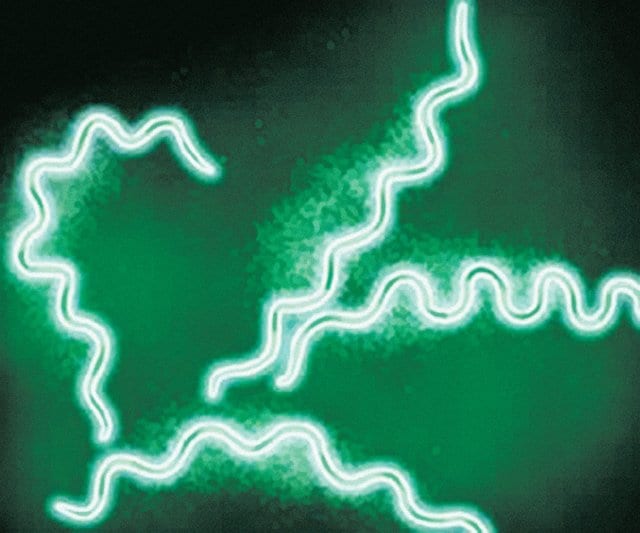

In technical terms, a bacterium called Treponema pallidum causes syphilis. It gets into the bloodstream and spreads throughout the body. And it’s easy to get by sucking raw cock. Thankfully, it’s also easily cured with penicillin. But you have to know you have it to get treated. While antibiotics are hard on the body, secondary syphilis for a poz man is a serious health concern. A body that has been compromised from decades of living on HIV medication doesn’t need another burden. Left untreated, the infection advances, slowly wreaking havoc.

The spread of syphilis began to rocket in 2003. By 2009 Toronto had its first cases of tertiary syphilis (also called neurosyphilis) among MSM (men who have sex with men). The city had not seen a case of tertiary syphilis in decades — it normally takes decades to manifest. But for those already living with HIV, it can develop in a year.

Syphilis is everywhere gay men are — and syphilis rates have soared since the early 2000s. More than 3,500 cases were reported in Berlin in 2011. In Sydney, Australia, infections peaked in 2009 at 1,458 — 96 percent of them among MSM. Meanwhile, 96 percent of Toronto’s syphilis infections are MSM: 779 cases in 2011. There were 26 reported cases of infectious neurosyphilis in Toronto in 2009/10.

Tertiary syphilis affects all organs of the body, spinal fluid and brain. In some cases bulbous growths appear on the skin, bones or liver. In others, it causes life-threatening meningitis: an inflammation of the brain and spinal cord causing headache, stiff neck, fever, mental confusion, sensitivity to light, fatigue, blindness and dementia. It can restrict blood flow to the heart, which can result in severe pain, a massive internal hemorrhage and death.

The reemergence of syphilis has also changed the nature of co-infection, which used to mean a combination of HIV and hepatitis C, says Sean Hosein, one of the founders of the Canadian AIDS Treatment Information Exchange (CATIE). Now, co-infection can include any combination of HIV, hep C and syphilis. “We changed our mandate a few years ago when hep C co-infection became more of an issue. Our chief mandate was around HIV, then expanded to include hep C. Syphilis helps HIV spread, which is why we talk about it.”

According to the Public Health Agency of Canada, 26 percent of HIV-positive Canadians do not know they are infected. Hosein says reports from England and the United States show that some HIV-positive men are contracting syphilitic hepatitis, which occurs when germs attack the liver.

Sex and drugs

Barebacking and the widespread use of crystal meth exacerbate the spread of sexually transmitted infections like syphilis, Hosein says. “Crystal meth dries up the mucous membranes and it’s deeply addictive. Viagra can enable bouts of prolonged and frequent sex. If such sex is unprotected, your risk for STIs goes up.”

At the height of the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s, gay men started using condoms for anal sex; sucking cock was determined to be low risk. Then in 1996 the cocktail of drugs appeared and began prolonging lives, and HIV-positive men became healthy and sexually active again. But discrimination and stigma persist. Poz men often don’t want the responsibility of playing with negative men, and negative men sometimes see positive men as damaged goods. The increased criminalization of HIV has added to this divide. And the fear is that if HIV can be criminalized, why not syphilis?

According to John Maxwell, director of programs and services at the AIDS Committee of Toronto, “Canada has the unfortunate distinction of being one of the worst countries in the world about disclosure.” Maxwell says Section 22 of Ontario’s Health Protection and Promotion Act allows doctors to issue an order that is tantamount to a quarantine from sex. Failure to comply can lead to detention in a medical facility.

A 2012 study published in the Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care shows that these laws have affected people’s willingness to get tested for HIV and made them afraid to speak with medical staff about their sexual practices. There is currently no specific law criminalizing the spread of syphilis, but there is fear of testing positive for it, which many worry could be used as proof that they have had unprotected sex — thus possibly leading to charges for HIV nondisclosure.

But there are ways to get around a flawed system. “You can go to a doctor and get treated without being tested if you’re worried about your public health record,” says Kyle Vose, an HIV educator with PWA and Fife House. “After getting treated, then get tested. Tell your doctor you had sex with someone who turned out to have it. It saves the system money and you get treated right away, and it saves your public health record and costs only one test. Also, it can take two weeks to a month to get syphilis results, which is a long time.”

Vose required nearly a month of treatment on IV to cure tertiary syphilis. He currently lives in a threesome and says each man gets tested every three months, and they alternate monthly, so that one of the three is being tested every month. “If syphilis isn’t properly treated it can come back. It looks like it went away, but if people don’t get retested because they think it was treated and don’t need to worry — surprise, it’s neurosyphilis.”

What about drugs? For an increasing number of gay men, a weekend is not complete unless they get high, and sex is not sex without drugs. What about the porn that fetishizes infection? Or porn with people shooting up, turning from awkward and shy to cocksure performance artists?

Marco Posadas runs a bathhouse counselling program called TowelTalk for gay and bisexual men and MSM. He says substance abuse has always been a problem in the community. “Pain in any population is very difficult to talk about. This includes our feelings, our experiences with mental health and sexual health . . . we’re not trained at home to talk about these things. Substances have always been helpful for both men and women to help people to connect and access emotional expression.”

Reinfection: A vicious cycle

David Fisman, an infectious diseases epidemiologist at the Dalla Lana School of Public Health at the University of Toronto, conducted a non-traditional medical study based on a mathematical model — what he calls a “SimCity” study. It included a population of guys in a city like Toronto and looked at how people partner up and what happens when they get treated for syphilis.

“What’s interesting about the model is that the syphilis outbreak wants to rebound,” Fisman says. “When you treat those guys they become susceptible to being infected again. It’s like putting out a wildfire by covering it with dry grass.” But Fisman says there’s a threshold. “If we can get high-risk guys tested every three months, this self-correcting part falls apart. As soon as you’re reinfected, you’re tested and treated. Toronto, Ottawa, Montreal: we’re not the only people in North America who have a syphilis resurgence. Everybody’s struggling with this. It may be the fact that treatment works, but in the absence of changes in sex behaviour it just puts people back into where they can be reinfected again.”

There’s a curveball, however, for those who are HIV-positive and infected with syphilis, Fisman says. “In someone with advanced HIV disease, the usual patterns of syphilis change. People can have neurological complaints with early syphilis and bad meningitis, which means an infection in the lining of the brain. They can end up with syphilis in the brain much more rapidly.”

There’s been a lot of research into this particular epidemic, which can be viewed as a never-ending cycle; once in the pool, reinfection continues over and over again.

Darrell Tan is an assistant professor at the University of Toronto Faculty of Medicine and an infectious-diseases physician at St Michael’s and Toronto General hospitals. He is currently researching the treatment failure among HIV-positive men. “We certainly are seeing some serological treatment failure,” he says. “The challenge with this study is that we don’t have a control group, so I can’t tell you how different this is from the HIV-uninfected population. Other studies done around the world have similar results, generally showing that the serological response to syphilis is a little worse in a setting of HIV.

“The concern is that there have been lots of reports in the literature of clinical treatment failure or relapse in the setting of HIV.”

Syphilis combined with HIV is still relatively new when it comes to research studies. “We don’t have a good way of testing microbiologic treatment failure, a scenario where we give someone treatment but the bacterium remains in their system at a low level that could lead to problems down the line,” Tan says.

Tan is most concerned about neurosyphilis: “It can be sequestered in a part of the body that is hard to have antibiotics penetrate, such as the central nervous system.

“Penicillin is an extremely good treatment. We’re forced to use the antibodies as a proxy for adequate microbiologic cure of the infection. It’s recognized that serologic treatment failure occurs a modest amount of the time. Microbiological treatment failure definitely does occur. But we can only measure serologic treatment failures or reinfection, which are impossible to tell apart.”

Testing and awareness

Ann Burchell has been studying HIV and other STIs since the mid-1990s. She has focused her research on HIV-positive MSM and reports that testing rates have been increasing alongside syphilis outbreaks. In 2000, less than five percent of HIV-positive gay men had at least one syphilis test a year. In 2009, 53 percent had been tested for syphilis in the last year. “That means half were not being tested,” she says. “In 2011 we started to look at sexual behaviour, and we found that even among the men who reported five or more sexual partners in the past three months, 70 percent had had a syphilis test in the past year, which means 30 percent had not.”

Based on her test results, Burchell says about 23 percent of gay men with HIV — one in four — have had syphilis. “It’s estimated that the prevalence of HIV among gay men in Toronto is currently about 18 percent,” she says. “The rate of first diagnosis of syphilis among HIV-positive men is three percent per year. The rate of rediagnosis is five percent per year, and we think that at least half of the rediagnoses are reinfections.”

This means that unless something changes, people who have been getting syphilis are going to keep getting it. “It’s not a random roll of the dice of what man gets syphilis,” Burchell says. “The tricky thing in public health is that it can be very difficult to identify the people who need to have repeated testing.”

Burchell says one option is to test for syphilis every time HIV-positive men have routine lab tests, which is common practice in the UK and Australia. Other interventions can focus on sexual behaviours. People need to get diagnosed quickly and treated quickly. Fisman agrees that frequent testing is important: “It doesn’t eradicate syphilis, but it has an impact.”

Burchell sees a strong need for more public funding for outreach and testing. “We would like to pilot routine syphilis testing with HIV blood testing and are requesting funds to do so in Toronto and Ottawa. You’d detect more of them, and earlier, which would reduce transmissions. The earlier you get diagnosed, the simpler the treatment.”

Another issue involves medical care. The Hassle Free Clinic’s Shawn Fowler says nurses at the downtown Toronto clinic commonly see patients who have been to several healthcare providers and have been repeatedly misdiagnosed. “It’s the perfect storm, with the proliferation of barebacking sites that have emerged over the last 10 to 15 years and the transition from picking up in bars to online,” he says, noting Hassle Free recently did an HIV and syphilis testing “blitz” because infections have been on the rise. “We see a correlation between testing positive for syphilis and HIV… We need to raise awareness about how to be screened. Criminalization of HIV, personal rights, mistrust of public health are concerns people have… we hear horror stories about how some people have been treated.”

Over the last several years Toronto Public Health and community organizations have made an effort to reduce the spread of syphilis. Special one-time funding from the city and province allowed ACT to do a large-scale syphilis awareness campaign in 2009. For Pride 2012, the city’s AIDS service organizations got together to create postcards that said “So You Like to Fuck?” that directed people to a site with information on sexual health, including issues of syphilis.

Still, Fowler says, not enough people are listening.

For more information on this topic, go to thesexyouwant.ca.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra