I was born with spina bifida (SB), a congenital disability that impacts neurological development of the spine. In the medical community, SB is referred to as “the snowflake condition” since no two cases will present the same. For me, it means that I have a lipomyelomeningocele (a fatty mass attached to my spine), a tethered spinal cord and I experience partial paralysis from my lower back down. I’m still learning what is and isn’t caused by my spina bifida, but I can say that I’m ambulatory, or able to walk, but not all the nerves from my waist down developed typically.

As a disabled person, my relationship with the queer community at large has been fraught with cultural and access barriers. These spaces may be safer for my queer identity, but only if I’m able to divorce it from my race and ethnicity or my disabilities. COVID-19 exemplified this perfectly, as many queer spaces casually “returned back to normal,” excluding disabled queers who might be at a greater risk of dying from the virus should they be infected.

Over the last few years as I’ve connected with disabled community, I’ve seen networks of queers with shared disabilities find and support one another. But as well connected to the queer disability community as I’ve become, I still struggle to find other LGBTQ2S+ people with spina bifida. SB is the most common “birth defect” in Canada, yet it was only after writing a widely shared article in which I mentioned my diagnosis that I started to meet other SB folks virtually.

October is Spina Bifida Awareness Month. This year, I knew I wanted to bring attention to the fact that SB exists in the queer community—and to give people with SB the visibility to find one another and build our own community. So, I spoke with queer SBers from across North America about their journey finding their queer identity, representation and the importance of community.

The struggle with identity

For much of my life, I struggled with internalized ableism and distanced myself from my spina bifida as much as I could. I felt that my queerness was easier for others around me to accept than my disability was, and I didn’t want to be seen as a burden.

But others I’ve met said they experienced the opposite.

“My disability was something that was always first in my life,” says Andrea Lausell, a Los Angeles-based Latinx digital creator I met online in 2019. “I think I learned how to say lipomyelomeningocele before I said I’m a boricua (a person from Puerto Rico).”

For Lausell, identifying as disabled was about safety—to get accommodations or to have her limitations taken seriously. But her focus on disability and having to advocate for her own needs also meant she didn’t have a chance to explore her queerness.

As Baltimore-based visual artist and disability advocate Celeste Tooth noted, stereotypes around disability and medical trauma play a huge role in that.

“I think everyone who is queer—especially growing up in a conservative area—struggles with identifying [their sexuality] without [also] being told that you’re a desexualized being because you’re disabled.” Tooth described how their earliest experiences of having their body touched were in medical contexts, dissociating it from sexuality in their mind.

Syd Chasteen, a demisexual and agender disability blogger from Southern Indiana, agrees, saying they found it complicated to untangle their personal identities from that desexualization and to move past “all those ‘truths’ that we grew up with: that your dating pool is nonexistent; you aren’t a sexual being; you don’t have a gender. You’re just disabled.”

Finding queer community

Understanding your identity becomes more complicated when you straddle multiple communities. It’s all the more isolating when the communities that are supposed to embrace you further marginalize you instead.

“In the queer community, we’re supposed to be all about accepting differences … and celebrating things that are not really celebrated in the mainstream,” said Tooth. “But then when it [comes to] disabled queer people trying to be part of the larger queer community, I feel like the community sometimes just mimics society at large.”

Just disclosing your disability can shrink the number of connections you can make. “That part weeds out 50 percent, let’s say, of the people that I run into in queer spaces,” says Keith Sadler, a Kansas City-based writer.

When it comes to dating, Sadler says that in his experience, non-disabled people may be reluctant to start dating a disabled partner—or may quickly become overwhelmed once they get a closer look at the barriers we have to navigate in our daily lives.

At the same time, mainstream disability communities can feel just as oppressive. Since spina bifida is a congenital condition, SBers start receiving pressure to conform from birth. “So much emphasis is placed on prevention and babies and helping little kids be more ‘normal,’” says Chasteen. That becomes a community-wide pressure to be the most palatable and acceptable kind of disabled person possible.

Lausell, whose spina bifida developed because her father was exposed to Agent Orange when conscripted into the Vietnam War, points out that being “palatable” to the mainstream isn’t possible—or even desirable—for her. “I still have this anger when it comes to U.S. imperialism. I wouldn’t have had my spina bifida if the U.S. didn’t see brown bodies and my dad’s brown body as disposable.”

Obstacles to connecting

Between physical inaccessibility, dropping COVID-19 precautions and a lack of financial and community resources, many SBers I spoke with said that it’s hard to find spaces to meet and gather in both in-person and online.

This isolation is complicated by the fact that for SBers, adulthood is practically unprecedented. It was only within the last 40 years that the medical community decided that the majority of SB babies were worth trying to “save.”

We can’t look to elders for advice on how to build community or what our lives may look like in the future because, as Tooth explained, our surgeries are still experimental and there aren’t many older SBers to learn from. “It’s this experience of not knowing where you’re gonna be even in a couple of months or a year.”

That disconnection from others’ experiences, especially when they can be so specific and varied, leads to an apprehension to finding one another. Even how we experience paralysis can range from walking independently to being a full-time powerchair user. It can feel even more disappointing to be unable to relate to another when they’re the only person you know who shares your identity.

The scarcity of community can even complicate our relationships when we do manage to find each other. Aidyn Alexander, a Toronto-based 33-year-old had the rare experience of dating another SB teen in high school, during which time they both came out as queer and trans. When the relationship became toxic, it was harder for Alexander to let go.

“I didn’t know if I was ever gonna meet someone who has these identities again,” he says.

Forging our futures together

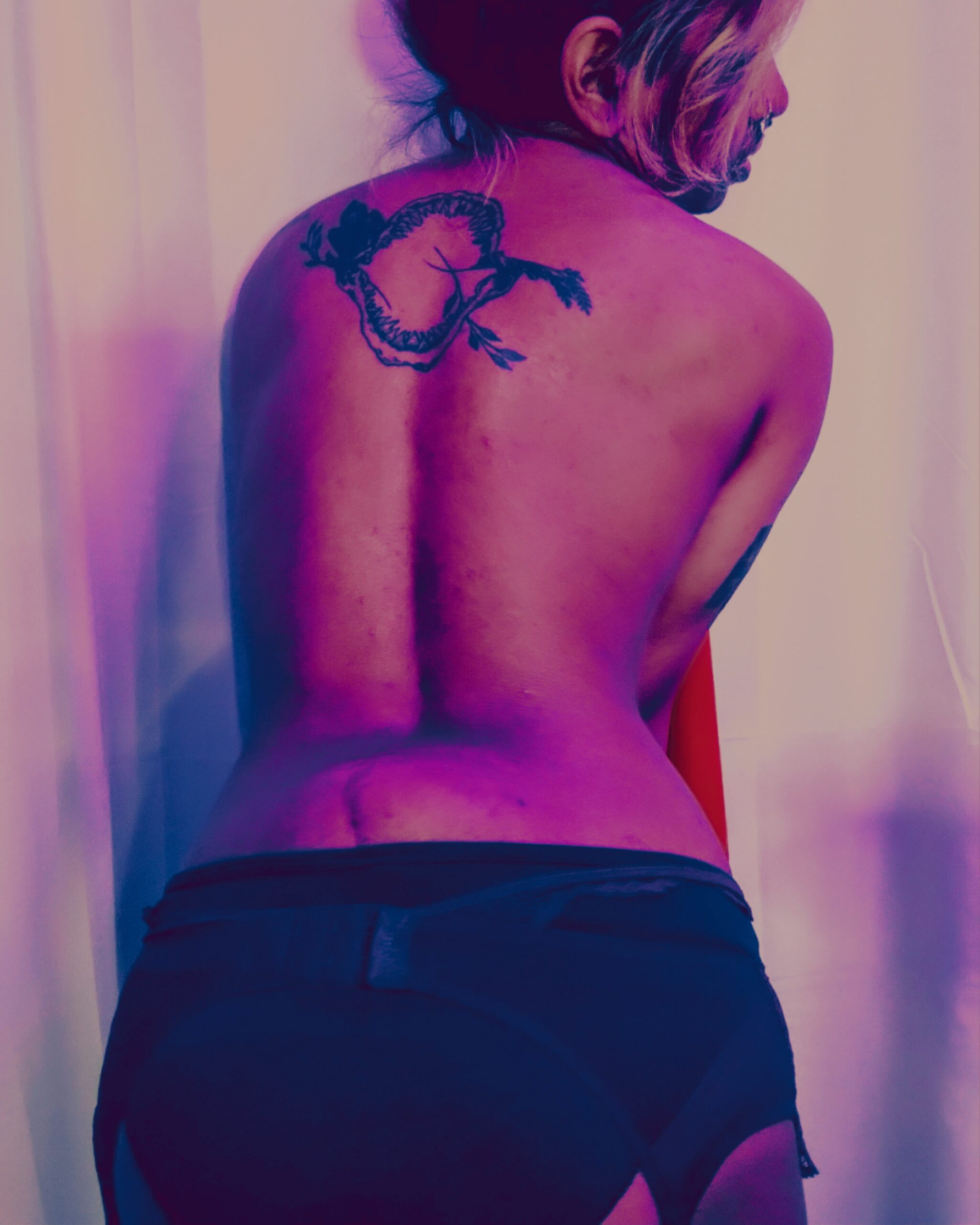

Despite the challenges, finding each other is life-changing. Lausell was the first person I met who had the same type of SB as me. I used to be so ashamed of my bump, thinking it made me undesirable. Connecting to Lausell’s work, I realized that hiding my bump prevented others from truly knowing me. So I began to share photos of it online, unknowingly giving something back to her.

“I remember crying to [my roommate] because your back was the first back I’ve seen with a bump that looks like mine,” Laussell says.

Finding people who reflect our experiences doesn’t just help us feel less alone, but also gives us new possibilities to envision for our futures. This is what Jay Anaya, a California-based chicana, realized when she finally found her queerness.

Before coming out, Anaya had been in a relationship with a straight cis man, but the heteronormative expectations for relationships felt inaccessible. “He was expecting me to have children. And then I go, ‘Wait, I don’t even know what’s gonna happen to me [if I do],’” she says. Coming out as queer allowed her to imagine relationships outside those expectations. “I just see more options of living.”

Finding content creators like Lausell who shared so many of her identities also allowed Anaya to start openly identifying as disabled and sharing her experiences online.

“Having people like you, who understand your experience, who are going to validate your experience, and who are going to uplift you as you are as a person is really beneficial,” Tooth shared. “Even just having a few people in your corner who are not on this push for being as normal as [you possibly] can be.”

It also means being able to share resources and strategies to help one another. Even as we near ages we were supposed to be lucky to reach, like myself and Lausell, there’s no such thing as too little, too late. It’s still worth trying to change the narrative, if not for ourselves, then for the youth growing up with SB now.

“I’m probably not gonna have my dreams happen, but I’d rather die at least knowing that the kids with spina bifida don’t have to have the same shit we have to do,” says Lausell. “They’re gonna have their own shit, but they shouldn’t have our shit.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra