It works like the birth control pill. It’s a once-a-day tablet. It can have side effects, but for most, it’s relatively safe. Like birth control, it works only if you actually take it every day. And it doesn’t prevent sexually transmitted infections like chlamydia and gonorrhea.

The difference is this pill doesn’t prevent pregnancy. It prevents HIV.

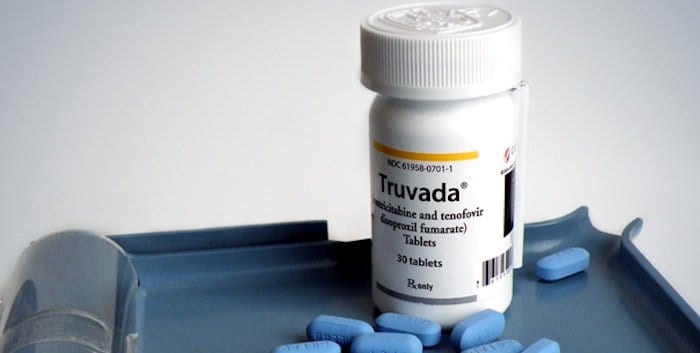

The drug is Truvada, which is a common first-line treatment for people who are HIV-positive. But doctors are beginning to prescribe it to people who are HIV-negative as a way of keeping them negative, part of a strategy called pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP for short.

In the United States and the United Kingdom, PrEP has sparked a protracted, public shouting match between its supporters and opponents, who ask whether PrEP is good — not just whether it works, but whether it is something scientists should be researching.

The debate about PrEP has not reached a fevered pitch in Canada, at least not yet.

However, the intensity of the international debate about PrEP has left its mark. Most of the Canadians I spoke to for this story — on and off the record, inside and outside the AIDS establishment — are to some degree hesitant.

In on-the-record interviews, a common rhythm developed. I would ask a question. The question would hang in the air for several seconds before I received a careful, measured sound bite.

The drug is not approved for use as PrEP in Canada, yet some doctors are prescribing it anyway, an arrangement that is unusual, although not illegal. Health officials in Quebec have even released guidance for doctors who are prescribing PrEP — even though it’s not approved.

Stranger still, Gilead, the company that makes Truvada, has not even applied for approval in Canada. Has the controversy over PrEP made Gilead shy about seeking approval? Or is there another reason?

Canadians are already taking PrEP

Marc-André LeBlanc began taking PrEP in 2013.

LeBlanc, who lives in Gatineau, Quebec, read about PrEP’s deployment in the US. He found himself thinking a lot about US guidelines — guidance that recommends PrEP for people who are unable or unwilling to consistently use condoms and who are at high risk for HIV.

He’d noticed his own condom use slipping over the previous three years. Eventually, he concluded that PrEP was right for him. He gathered material, including pamphlets, scientific studies and the American guidelines. He took the information to his doctor.

It turned out that his doctor — a gay man with lots of HIV-positive patients — already knew about PrEP. They discussed LeBlanc’s risk profile. His doctor ordered a full round of tests for sexually transmitted infections, including HIV, as well as a test to determine kidney health. At a follow-up appointment, his doctor prescribed Truvada. LeBlanc returns for STI and kidney testing every three months. “I just take it with my vitamins, which I’ve been taking for years,” he says. “It’s already part of my routine, so that made it super easy to add Truvada. It’s been seven months, and as far as I know, I haven’t missed a pill.”

LeBlanc’s story highlights some of the hoops Canadians must jump through to access PrEP. First, you have to have a family doctor. And not any doctor will do: you have to feel comfortable talking to him or her about sex. And your doctor has to be knowledgeable (or at least prepared to learn) about HIV — and willing to prescribe a drug off-label.

But the bigger barrier may be price. It costs more than $850 a month. LeBlanc, who is covered by Quebec’s provincial prescription drug plan, pays just $80 a month, with the rest of the tab picked up by the province. “Cost is a big [problem]. If I had to pay the almost $900 a month, that was going to be a nonstarter. If I had to pay that out of pocket, I absolutely wouldn’t be on PrEP,” he says.

It’s a different story in the rest of the country, which doesn’t have a universal prescription drug coverage. For those with private drug plans, coverage will depend on how Truvada is listed in the plan. In any insurance scheme, a drug may be covered generally or it may be covered only for particular uses.

For Toronto’s Len Tooley, who uses PrEP, the drug is covered by his employer’s insurance plan. He agrees with LeBlanc that cost — along with access to a non-judgmental doctor — can be a major roadblock for those who might otherwise be interested in PrEP.

A third factor, Tooley says, is knowledge. Both LeBlanc and Tooley have worked in the AIDS movement; for them, reading the latest research on HIV is all part of a day’s work. But for the rest of the country, awareness about PrEP remains low.

Does PrEP work?

The first study to conclude that PrEP reduces HIV risk was released three years ago. It immediately became controversial, and it’s cited by both PrEP supporters and skeptics. To explain why requires a little background on the study itself.

Researchers tracked 2,499 gay men and trans women; half were given Truvada and half a placebo. Researchers asked them all to take the pill every day.

On first blush, the results were less than stellar. The study concluded that the Truvada group experienced a 44-percent reduction of their risk of HIV transmission. Such a reduction is large enough to show that the drug has an effect but perhaps not strong enough to recommend it as an effective prevention strategy.

But here is where things get complicated. In the study, blood testing revealed only about half of participants given Truvada were actually taking the pills. And, in particular, these tests revealed that every one of the men who tested positive for HIV in that group either took the drug irregularly or not at all. The study concluded, tentatively, that Truvada is 92-percent effective, if taken every day. And a subsequent study using the same data and different modelling produced an even rosier number: if Truvada is taken seven days a week, it’s 99-percent effective, researchers found.

Now, these conclusions are less reliable, because the sample size is smaller — 34 newly HIV-positive people, compared to almost 2,500 in the larger study — and not protected by randomization. Therefore, other behavioural factors, such as condom use, could have influenced the results.

So why weren’t participants taking the pill every day? Darrell Tan, a doctor and researcher at St Michael’s Hospital in Toronto, says that people’s attitudes during trials can distort research. “The motivations for taking a drug consistently in a clinical trial could be different than the motivations for taking it in real life,” Tan says.

Tan is launching a new pilot study of PrEP in Toronto in the coming months. He’ll be putting PrEP into the hands of participants outside the clinical trial setting. In other words, the people he will be studying know that they are taking Truvada, not a placebo, and they will be told that the drug has been shown to work.

“PrEP is not a purely biomedical thing. It’s also a behavioural thing. Therefore, the only way to know for sure how effective PrEP will be in real life is to try it in real life.”

Adherence has become one of the central questions of PrEP. Tan’s study will come on the heels of other studies that have had less optimistic results. Researchers halted one study of women in Kenya, Tanzania and South Africa early because it found no correlation between those given Truvada and those given a placebo. Again, poor adherence was blamed for the results.

There’s a big difference between 44 percent and 99 percent, obviously. The most partisan players in the US will often use one or the other of these stats, usually without explaining the bigger picture.

James Wilton, coordinator of the biomedical science of HIV prevention project at CATIE, has been following PrEP. He’s excited by what he’s seen so far. The bottom line, he says, is that PrEP works — and it works better when taken consistently. He says there is some promising research showing that consistent use of PrEP may be more than 90-percent effective, but we don’t know for sure because of the limitations of the studies. However — because of study limitations and difficulties in identifying study participants who are taking PrEP consistently — right now we can’t be more precise than that.

Robert Grant, the lead researcher on the first major study, recently told Xtra that he believes PrEP is “more than 99-percent” effective. (Watch that interview.)

Wilton adds that most common side effects of PrEP are relatively minor, like nausea, and they tend to disappear after the first few weeks. In a small number of participants, Truvada has led to more serious side effects, including kidney damage and reduced bone mineral density. But even kidney risks have tended to return to normal once patients stop taking the drug.

“So far, the randomized clinical trials do show that Truvada is generally pretty safe for HIV-negative people to take,” Wilton says. “But you have to understand, for HIV-positive people, treatment is taken for the rest of your life. Whereas PrEP is not necessarily an intervention that would be used for a long period of time. It may be months or a few years, but probably not your whole life, and therefore, the long-term impacts, the side effects, the toxicities may be smaller. But it is certainly something someone needs to consider before taking PrEP.”

Will condoms become antiques?

You must wear a condom every time you have sex, even if you’re on PrEP. That is the message Tooley received when he was prescribed it by his doctor.

Tooley’s doctor was following American guidelines, which is itself something of a paradox: they recommend PrEP for folks who are at high risk for HIV transmission and who are unable or unwilling to use condoms. But they also recommend using a condom every time you have sex, even after you start taking the pills.

Let’s admit that it’s difficult to talk about the realities of condom use among gay men. We tend to think of ourselves as either condom users or barebackers. But the reality is that most gay men have had sex both with and without condoms at some point in their lives.

At the same time, safer-sex messaging for 30 years has had a singular message: use a condom every time you have sex.

“Wearing condoms became associated among gay men with being a good citizen,” LeBlanc says. “So now that there are prevention options — plural — we’ve sort of painted ourselves into a corner.”

If you’re already barebacking, PrEP will reduce your risk. But if you start taking PrEP and drop condoms — well, no one is recommending that. Why?

For one thing, condom use is highly effective, at least in theory. In practice, it depends on proper usage, lube and the condom not breaking. It also depends on people actually using them, and we know that people tend to over-report condom adherence in research studies.

Given those variables, it’s hard to say that condom use as it’s actually practised is more effective than PrEP, or the other way around. But if PrEP can even roughly approximate the risk reduction of condom use, we have to admit that it will change the math on condoms for some gay men, especially those who find the downsides of condom use — reduced sensation, reduced pleasure or reduced intimacy — to be significant.

Both LeBlanc and Tooley say they used condoms before starting PrEP but not always. And now?

“I am curious to know how people would react differently depending on how I answered that question. PrEP or not, my behaviours have changed over time, my relationship status has changed over time, but I think that’s not out of the ordinary,” Tooley says.

LeBlanc, who has been keeping a journal of his sexual practices over the last several years, says that his trend away from condom use pre-dated PrEP.

“I’ve committed to looking at my risk behaviour over the last several months to see if it’s changed my behaviour,” LeBlanc says. “My gut instinct is that condom use has not increased. But it’s that old question: is it cause or is it effect? The fact is, I introduced Truvada when I was already taking more risks.”

But LeBlanc also points to a curious research finding. From the randomized control studies, people who have been on PrEP have reduced their risk behaviours, not increased them, he says.

“And you can understand that, because when you’re on Truvada, you have to constantly report to your doctor, and that is an opportunity to stop and reflect on your sexual practices and risk behaviours and be more conscientious about what you do.”

Another way of thinking about risk

Most studies are presented in the media in a way that makes them sound more dramatic than they are. Think of the risk of infection as a pie chart. If you reduce your risk by 90 percent, your remaining risk is a 10th of the pie. Easy.

Easy, that is, but wrong, according to Cindy Patton, a professor at Simon Fraser University. Without introducing PrEP, the risk isn’t 100 percent. For unprotected anal sex with an HIV-positive partner, your average risk is actually pretty small, in the neighbourhood of 1.2 to 2 percent, although, again, it depends on which study you believe.

But all studies of per-act risk of transmission agree: most of the pie chart is already empty. That means that a 90-percent reduction would change the preexisting risk much less, probably reducing it by roughly one percentage point (for instance, from 1.2 percent to .12 percent). It’s a lot more modest than what the headline-grabbing stats suggest.

“So, the touting of a ‘dramatic reduction’ for any individual is simply unknowable. One percent is very small,” writes Patton, who is on sabbatical and corresponded with Xtra by email. “Basically, you’re a little un-careful, and very unlucky if you get infected with HIV. You are among a good minority if you have a side effect from Truvada.”

It’s also worth remembering that risk fluctuates depending on what people are actually doing in bed.

“Getting infected on any given occasion depends on whether the other person has HIV, how infectious they are at that moment, and whether you ‘receive’ their semen anally, vaginally or orally. That is a lot of contingencies.”

And that gives rise to another, less flattering comparison between PrEP and the birth control pill. The risk of pregnancy, for most of a woman’s ovulation cycle, is relatively low, in the same ballpark as HIV transmission during anal sex, Patton says. Like Truvada, the birth control pill has side effects, and those were more pronounced in the pill’s early days. As well, there are many ways to reduce the risk of pregnancy without taking a pill, in the same way there is with HIV transmission.

And so, before the pill could be adopted, large numbers of women needed to be convinced that transmission was otherwise impossible to control and very likely to occur, Patton points out.

If you take those lessons and apply them to PrEP, the warning is potentially very chilling. There’s a danger that, in order to sell PrEP to a broad demographic, HIV-positive people will be painted as extremely infectious or reckless or even duplicitous. Or that condoms will be publicly slagged as inconvenient, imperfect and a buzz kill.

Is it worth it?

At heart, the two biggest and most controversial questions are bound up together: who should be taking PrEP and is it worth it? It’s a point where Tan, who is doing research on PrEP, and Patton, one of its critics, may actually agree.

Consider this. In one scenario, we draw the boundary narrowly. Only the highest-risk people should be on PrEP, folks who, for instance, never use condoms and have sex with multiple unknown partners a week. In that scenario, we don’t have to write very many prescriptions to prevent a new HIV infection.

In another scenario, you draw the boundary more broadly. In this scenario, we include people who have sex less often and who usually wear condoms but sometimes slip up. This larger group’s risk profile is already much lower, and so you’d have to put more people — 10 times more, say — on PrEP to prevent each new infection.

If you’re weighing the costs of giving the drug to many people to prevent one new infection, then the costs are high. There’s no doubt that PrEP as it’s currently used is resource intensive: doctors’ appointments every three months, lab tests and more than $10,000 of pills per patient per year. And there are also the health costs, including nausea and other symptoms when a patient starts, the risk of serious kidney problems in the medium term, and longer-term effects that may not be totally clear yet.

In that sense, the first generation of PrEP makes sense only for people who are at high risk. But what behaviours, exactly, would put someone into that category? At this point, Tan admits, we just don’t know where to draw the line.

Will HIV-positive people lose out?

Perhaps most troubling, there is a risk that if HIV-prevention becomes more PrEP focused, it will divert attention and resources from people who are living with HIV.

In a recent article in the Journal of Bioethical Inquiry, Patton sharply criticizes the South African study of PrEP for women. It was halted because of poor adherence, meaning that the women in the study weren’t taking the pills. One theory of their poor adherence was that, because there was a 50-percent chance that they were getting a sugar pill, there wasn’t a sense of urgency about taking it.

The other theory is that, in areas where HIV medication isn’t widely available, the women in the study were giving the pills to their HIV-positive loved ones, hoping it was the real deal. The study highlights an ethical dilemma about giving HIV-negative people pills that are urgently needed for people who are positive.

A milder form of this conundrum has been raised in Quebec. If there is a surge in prescriptions for Truvada used off-label as PrEP, health officials may be inclined to tighten the rules, for instance by requiring proof that you are HIV-positive before your drug plan will cover the costs. And that would be an extra barrier — essentially more paperwork, perhaps an extra doctor’s visit — to HIV-positive people getting treatment.

Given that PrEP is resource intensive, we can’t yet say for sure what the implications are for others who are HIV-positive and whose access to treatment is already precarious.

But Tooley says there’s another way of looking at PrEP. It’s not a zero-sum game, in which providing Truvada to an HIV-negative person takes the pill away from folks who are positive. “If there are more people who are impacted by access, including now some HIV-negative people, it has the potential to improve access for all.”

PrEP isn’t a bogeyman that will keep pills from HIV-positive people. Instead of restricting access to PrEP, we need to double down on our commitments to eliminating barriers for positive people who need treatment, Tooley says. “Real factors affecting access to HIV meds by poz people are things like lack of comprehensive drug coverage, institutional barriers to healthcare access, being homeless or street-involved and deemed unable to be treated, or being non-status and having difficulty accessing medical services — to name a few.”

Will PrEP ever be approved in Canada?

PrEP is available in Canada, if you can find a doctor willing to prescribe it off-label. But PrEP hasn’t been approved by Health Canada. In fact, Gilead, the maker of Truvada, hasn’t even applied for approval. Why not?

Gilead won’t say. In correspondence with Xtra, Cara Miller, one of its California media reps, would say only that, while they haven’t applied, “discussions are ongoing with the Canadian regulatory agency.” What does that mean? It’s hard to say. It could mean that Gilead wants special treatment for PrEP in the approval process (which it got in the US). Or it could mean an application by Gilead was submitted but deemed incomplete. Or it could be a simple blow-off to a journalist thousands of kilometres away from Gilead’s headquarters.

Nonetheless, the fact that Gilead doesn’t have an application in the hopper at Health Canada is significant. One possibility is that Gilead isn’t strongly committed to using Truvada as PrEP.

In the high-stakes world of drug patents, the goal is to keep generic drug companies out of the market. One of the main ways to extend the life of a patent, and to therefore keep generics out, is to find what’s called “a new indication” for the drug. By doing so, you make it harder for a generic drug company to enter the market.

Truvada’s main use is as a first-line treatment for people who are HIV-positive. Doctors like to prescribe it because it’s relatively safe, in terms of side effects, and because it’s a simple once-a-day pill. Using Truvada as PrEP is a new indication, but it’s essentially a side show for Gilead.

After PrEP was approved in the US in 2012, fewer than 1,300 prescriptions were filled for it in the whole country. Those numbers are expected to rise this year, but not by much. Predictions for 2013 peg PrEP scripts at around 2,000. And that’s in the US, known for having some of the most inclusive formularies in the world. Insurance companies tend to cover a much broader range of drugs in the US.

It’s entirely possible that Gilead has done the math, and given the dismal uptake in the US, decided it’s not worth the cost of the application here in Canada.

Or, at least, not yet. It’s possible that interest in PrEP among gay men or other higher-risk groups may climb gradually, as more and more people become aware of it as an option. And research on other drugs and other methods of delivery that could be used as PrEP — for instance as an injectible — are coming down the pipeline, which will likely create more buzz.

But in the meantime, don’t expect a PrEP revolution anytime soon.

Watch our four-part video series on PrEP:

Part 1: Can a pill a day keep HIV away?

Part 2: A condom-free future?

Part 3: The controversy behind PrEP

Part 4: Why aren’t gay men taking PrEP?

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra