Four years ago, Jyssika Russell and two colleagues decided LGBTQ2 youth in Hamilton, Ontario, needed space. About an hour’s drive from Toronto, Hamilton has a population of nearly 750,000, a thriving arts scene, a large university. But there were no queer community centres. No gay bars. Some local non-profits ran LGBTQ2 programming, but nothing permanent that stood on its own. “For a city of this size, we had nothing,” Russell says.

Speqtrum is meant to be part of the solution. Russell and her co-founders designed the pilot project to provide active and social workshops for young LGBTQ2 people. Since then, Speqtrum’s offerings remain much the same. “Our whole premise is to create and build community, primarily through activities,” she says. “The idea is that then that can help you connect and support each other.”

But it is among the few offerings in Hamilton.

And that matters—especially in a city where xenophobic protesters have made a routine out of demonstrating; where a former neo-Nazi leader worked at city hall, openly, for years; and where, in 2018, the most hate crimes were reported in the country.

That hatefulness was demonstrated in full force at Pride 2019 in Hamilton’s Gage Park, when a group of protesters with homophobic signs showed up. According to the CBC, they physically clashed with counter-demonstrators who blocked them from the festivities. “A number of people in pink masks identifying themselves as anarchists manoeuvered a portable barrier to block them,” wrote CBC Hamilton reporter Samantha Craggs. “Punching, shoving and hitting broke out between the two groups. Several people were injured.”

Hamilton police were in attendance, but many felt they were slow to react. (An independent review of the incident, released in June 2020, found that the response to the violence was “inadequate.”) Meanwhile, Fred Eisenberger, Hamilton’s mayor, and some of the city council came under heavy criticism for not more forcefully denouncing the protesters—it took Eisenberger a week to release a formal statement. In the end, five people were charged: one of the homophobic demonstrators, and four of the counter-protesters.

A City of Hamilton spokesperson told Xtra that the city remains in solidarity with the LGBTQ2 community and is committed to being a “Hamilton for All,” where everyone in the city feels safe and welcome, and that they regret the violence that occurred at last year’s Pride event. “Mayor Eisenberger and Hamilton Police Service Chief Eric Girt apologized for the pain and fear experienced that day by our Two-Spirit and LGBTQ+ communities, their friends and allies.”

Hamilton is a city where marginalized communities have for years been trying to make space for themselves—through programs like Speqtrum and annual Pride events. But it’s also a city where hate has festered, particularly in the past few years. And it’s not alone: Research has found that right-wing extremism is growing worldwide. That’s why Hamilton’s queer community’s fight against homophobia and racism isn’t just their fight—it’s everyone’s.

“Hate does not emerge or operate in a vacuum,” wrote Barbara Perry and Ryan Scrivens in their 2018 research paper on how organized hate groups emerge in Canada. The pair, both researchers of right-wing extremism, found three patterns: a community history and normativity of racism, a political climate of intolerance and a weak law enforcement response.

You can find these patterns in Hamilton. “We have a history of hate groups in Hamilton that goes back over 80 years, as well as anti-Black racism within how we tell histories about Hamilton, and that is visible in leadership in Hamilton, across sectors,” Ameil Joseph, an associate professor of social work at McMaster University, told CBC Hamilton in 2019.

In 2001, for example, just four days after 9/11, a mosque and a Hindu temple were targeted in acts of arson. Three men were arrested 12 years later, and all pleaded guilty to a lesser charge of mischief.

In 2009, hate crimes were reported relatively more frequently in Hamilton the previous year than in any other city in the country. Credit: The Canadian Press/Frank Gunn

There’s a history of homophobia and intolerance toward LGBTQ2 people in the city, too. In the early 1990s, then-mayor Bob Morrow refused to declare Gay Pride Day; it would take a human rights tribunal ruling four years later to force him to recognize the day in Hamilton. Morrow, who was first elected in 1982, remains the longest serving mayor in Hamilton’s history—he didn’t leave until he lost the 2000 election. (He also came back to serve as an appointed councillor after a city councillor died in 2014.) Even in his final year as mayor, he still did not attend Pride events, according to a local Hamilton Spectator report.

Since then, Hamilton’s demographics have shifted significantly. It’s become a bit of a joke in Toronto for people, fed up by sky-high housing and living costs, to claim they are going to pick up and move to Hamilton—and some of them are actually doing it. In 2016, a Hamilton Spectator report found that newcomers to the area were “just as likely” to be migrating from other parts of the province than from another country, and that the largest generational group of people living in the city were millennials. And nearly one in four people in Hamilton under the age of 15 are people of colour. Perry and Scrivens note that when newcomers arrive, they are often seen as scapegoats for all sorts of social ills by a small subset of people who are more likely to become radical.

“We’ve had a number of people and youth connect with us coming from other places in the [Greater Toronto Area] before they move here, mainly coming here because of cheaper rent, more services and transit options than the suburbs,” says Russell. But, anecdotally, she noticed that some older LGBTQ2 people were doing the opposite—moving from Hamilton to Toronto for better access to safety and community.

Though the poverty level has lowered since the mid-’90s, it remains high compared to the Ontario average. There are also massive income disparities at the neighbourhood level, according to the Spectator: 11 neighbourhoods in the lower inner city still have poverty rates of more than 30 percent.

Hamilton has a strong tradition of union activism and, at the federal and provincial level, the downtown ridings have been NDP strongholds since at least 2006, while more affluent areas of Ancaster and Dundas have typically voted for the Conservatives or Liberals. Yet, in 2018, Hamilton recorded the highest reports of hate crimes in the country—almost triple that reported in Toronto, the biggest city in Canada.

“It wasn’t a surprise,” says Michael Abraham, the lead at the SPACE Youth Centre, a drop-in centre for youth that provides programming for LGBTQ2 people. “But it was so sad to see.”

In 2018, there were 18 incidents of hate bias against the LGBTQ2 community; 58 were because of racial bias and 49 were because of the victims’ religion. That was a slight decrease in the number of incidents due to bias against sexual orientation from the previous year, when there were 22 incidents.

Hamilton’s statistics in 2018 outstrip many other communities. Compared to the city—which had 17.1 hate crimes per 100,000 people—Ottawa, the third ranked at the time Statistics Canada released the information, had only 9.8.

And Kojo Damptey, the interim executive director of the Hamilton Centre for Civic Inclusion, notes those numbers are also likely underreported. “Those communities don’t have a good relationship with the police,” he says. Then there’s the issue of hate crime reporting: For an incident to be officially counted as a hate-motivated crime, it must be proven beyond a reasonable doubt that an actual crime occurred, and that it was motivated by hate. “If I’m walking downtown and somebody uses a racial slur at me, there is no chance that that person is going to be arrested,” says Damptey.

Meanwhile, the tenor of racist, homophobic and transphobic incidents in Hamilton seemed to be getting worse. “We’ve often had the usual sort of religious person standing up on the hill with a sandwich board [at Pride],” says Cole Gately, who was among organizers of Hamilton’s 2017 Pride events. But about three years ago, people Gately describes as street preachers came to protest, as well as people he believes may have been affiliated with white supremacist groups.

It was in late 2018 that the Yellow Vest movement—a group originating in France, protesting high gas and living costs, but that soon, in parts of Canada, intermingled with alt-right groups—made its way to city hall. The first recorded protest, in December that year, was against Canada signing the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration, an international agreement on a common approach to international migration.

After that, the protests at city hall became a weekly event, escalating into the confrontation at Pride—which left many people in vulnerable communities wondering why a public space had become a venue for xenophobia and intolerance. “Most of the leaders in our city and politicians said nothing,” says Cameron Kroetsch, who is on Hamilton’s LGBTQ advisory committee and the Pride board of directors. “That has been the status quo, from what I can tell, for a long time in Hamilton.” The city did eventually look into whether it could legally bar the group from a public space. A City of Hamilton spokesperson says that the city’s corporate security team continues to observe rallies and demonstrations that take place in municipal spaces such as the city hall forecourt, and—if there is reasonable evidence to substantiate a complaint—a trespass notice can be issued. So far, the city has issued two trespass notices related to violence by hate groups.

But more incidents have only increased friction in Hamilton. In 2019, a Vice investigation found Marc Lemire, a former neo-nazi leader, had been working at Hamilton City Hall for years, his name left off most of the city’s public facing records. (After this was disclosed, Hamilton’s LGBTQ advisory committee asked the city council not to fly the Pride flag at City Hall during Pride; instead, they didn’t have a flag raising ceremony.) And Paul Fromm, a known white supremacist, was spotted at the Yellow Vest protests, according to the CBC. Then came the Pride counter-protesters.

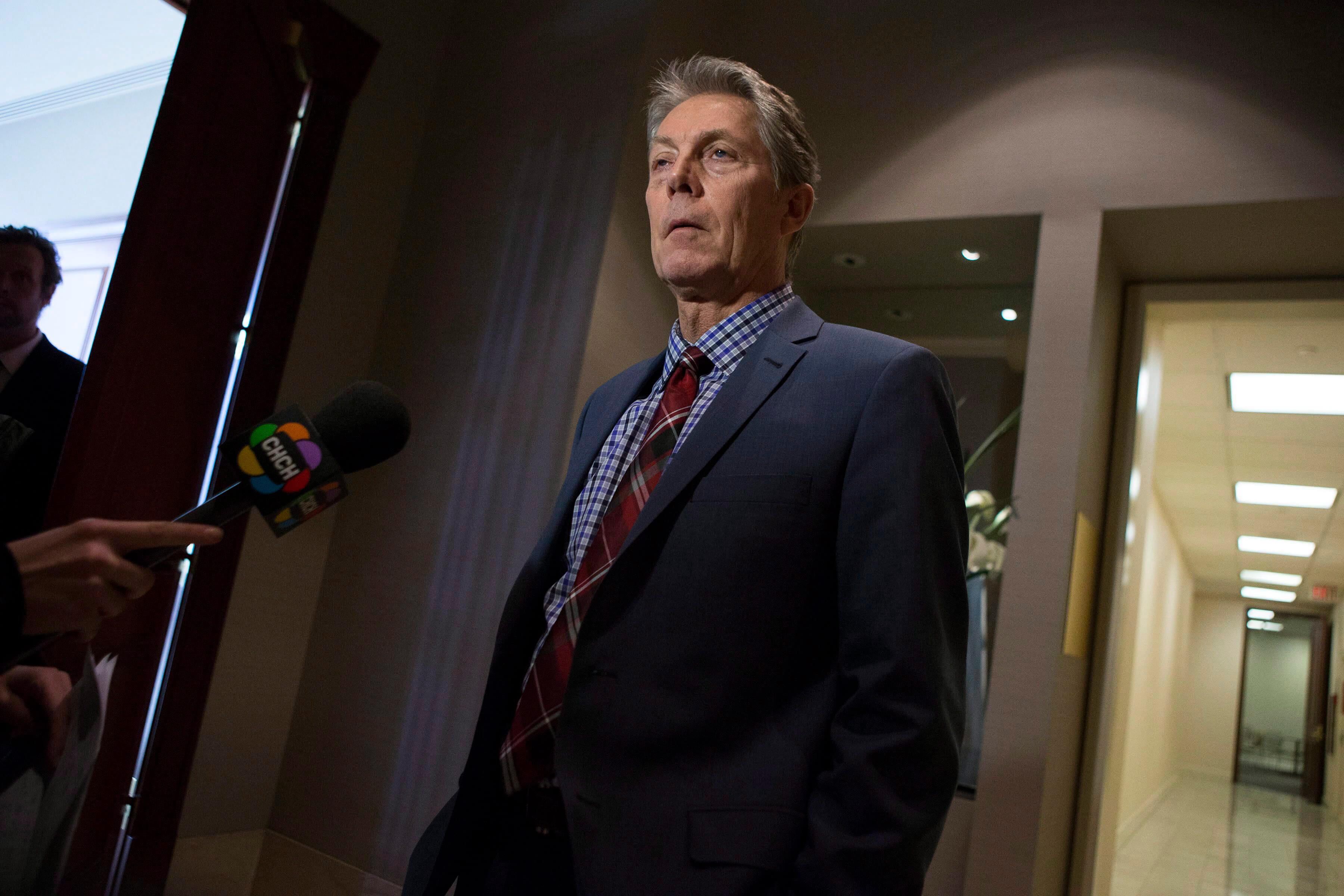

Hamilton Mayor Fred Eisenberger Credit: The Canadian Press/Chris Young

The overall situation became scary enough that some community organizers worried they were putting themselves at risk just by holding events. Chris Farias was the host of Drag Queen Storytime in Hamilton, performing as Ladybird Fancypants. After one performance at Carter Park in the fall of 2019, Farias came home to find they had messages from concerned friends after hearing that threats had been made against Ladybird Fancypants and the event. Suddenly, Farias had to weigh performing against the potential of putting children at risk. “I was scared that I was drawing hate to [kids],” they said. Since then, Farias has only held Drag Queen Storytime online or for private events.

This hate Hamilton is, in some ways, a microcosm of the troubling rise of right-wing extremism in pockets of North America. Perry and Scrivens note that across Western Ontario, Quebec, the lower British Columbia mainland and Alberta, “the economic transition and the demographic transitions that have affected [southern Canada] more than [northern Canada] have created a whole raft of anxieties for some elements of society.” London, Ontario—only about an hour-and-half drive from Hamilton—also had alt-right protests in 2017. Hate speech and hate-promoting activity became so problematic that, in 2017, the City of London announced that the managing director of parks and recreation would be able to refuse or revoke permission for events on city grounds if they believed it promoted hatred or discrimination,” writes Eternity Martis in her book They Said This Would Be Fun, a memoir about her experiences with racism while attending university in the city. (Martis is also a senior editor at Xtra.) “Hate incidents in the city have been so shocking that they’ve made national headlines.”

There’s evidence that organizers of the Hamilton Yellow Vest protests wanted to spread their movement further afield. According to the Canadian Anti-Hate Network, last year Justin Long, a member of the group, said in a video that “it’s his goal to clear anti-fascists out of Hamilton and then move on to another city—maybe Niagara Falls.”

“While not all white nationalists are homophobic, the majority of right-wing extremists are ‘virulently anti-LGBT’ and share an anxiety and fixation on white birth rates, which are just barely keeping pace with racial minorities,” writes Julie Compton for NBC News. And according to a 2020 United Nations Security Council Counter Terrorism Committee report, there has been a 320 percent rise in attacks by individuals affiliated with extreme right-wing terrorism in the last five years. This all combines to create a potentially dangerous situation for queer people.

That there are no permanent safe spaces for LGBTQ2 people wasn’t always the case in Hamilton. The Well was Hamilton’s queer community centre for 10 years. Embassy, one of a small handful of gay bars, was located smack downtown from the mid-1990s. Despite the best efforts of one former mayor, Pride festivities have been marked since the early ’90s.

But both The Well and Embassy closed in 2016. There have been some efforts to provide funds for LGBTQ2 communities: The city of Hamilton has a diversity and inclusion facilitator and, in 2018, installed rainbow sidewalks outside of city hall. But according to Joey Coleman, publisher of civic affairs news site The Public Record, there is no direct operational funding dedicated for LGBTQ2 programming aside from the facilitator position. A City of Hamilton spokesperson says that the city’s enrichment fund “applies an equity, diversity and inclusion lens to our grant process and engagement plans to ensure we are reaching all.” This includes grants for Pride Hamilton.

Hamilton’s lack of LGBTQ2 spaces is such an issue that while doing research for a survey of Hamilton’s queer community, Suzanne Mills, one of the authors of the report and an associate professor at McMaster University’s school of labour studies, noticed the town halls they were holding were very popular among queer and trans folks. “[The attendees] didn’t want to participate in the research at all,” Mills says. “They just wanted to meet people, that they would talk to about how they wanted social spaces and things to do.” The study, released in 2019, found that while Two-Spirit and LGBTQ people generally have a strong connection to Hamilton, fewer felt that same connection to the city’s queer community.

Mills’ research has also found that while LGBTQ2 folks generally feel safe in Hamilton, many do not feel safe outside or in places affiliated with religion. Racialized cisgender people and trans people felt less safe comparatively.

Creating space in the city has long been a unique challenge. But Adam George Palios and Steven Hilliard have tackled it headfirst—a reversal of sorts on the headlines about hate in Hamilton. Their promo company, Adam and Steve, is one of the biggest organizers of LGBTQ2 events in Hamilton. Last year, they hosted a Pride party in this midst of all the strife. There was not a homophobic protester to be found. Instead, 500 people showed up to celebrate queerness. “I remember walking around that night, genuinely in tears, seeing people I hadn’t seen in years, who, for the first time in so long, came out to Pride to celebrate,” says Hilliard. “I think that that is the measure of where a community is going.”

“Just holding safer space [can] also be very healing,” says Palios. “Just to know that you can go somewhere and relax with your friends and you don’t always have to be on edge.” In the absence of a dedicated gay bar, Palios and Hilliard instead work on educating staff at local venues on how to be a safe space for the queer community—whether that’s the club where they bring alumni from RuPaul’s Drag Race, or the local sports bar where they host Dirty Bingo.

Having space can be crucially important to stopping hate. And having a united front also shows that the community has strength and support from others. “Those sort of mechanisms [community centres] are so important for developing broader community support and developing allyship and solidarity, but also in deterring violence,” says Barbara Perry.

Mills’ study of Hamilton’s queer community found that there was a sizable minority of people who are leaving the city to access services and community spaces geared for LGBTQ2 people—and almost all of them would prefer not to leave. “There’s just a lot of people who feel lonely and disconnected,” Mills says.

While Hamilton lacks something permanent, other organizations have stepped up to support the LGBTQ2 community in the last few years. The AIDS Network provides more generalized non-AIDS related programming, according to Mills’ study. The Hamilton-Wentworth District School Board hosts Rainbow Prom, a safe space for youth to celebrate. Kaleidoscope is an LGBTQ+ youth circle co-founded by Kiwanis Boys and Girls Clubs of Hamilton and NGen Youth Centre.

In May 2018, The SPACE Youth Centre introduced OQRA, an informal support group for queer and trans Black, Indigenous and racialized youth, after hearing concerns from the community that even what little was for offer in Hamilton was overwhelmingly white. (The Centre also offers Scope, an LGBTQ2 youth circle.) But Michael Abraham says the team is also trying to bring an intersectional lens to everything they do at SPACE. “I think having spaces in which you can exist and flourish is a common need that pretty much anyone and everyone has,” he says. “So when you don’t see yourself represented in your community, or the wider city, that’s quite a challenge.”

Speqtrum’s Jyssika Russell believes that this kind of organizing work is what can effectively stomp out hate in Hamilton. “I think it’s just a perfect time to really highlight that what’s going to stop a hate crisis in Hamilton is investing in community organizations, into mental health supports, into affordable housing and into addictions programs,” Russell says. “These are the things that will actually alleviate so many of those community issues.”

There’s evidence that this kind of support for marginalized and vulnerable communities can push back against far-right radicalization. Perry and Scrivens reported that it’s often community activists who are able to see where hate is bubbling up and more effectively communicate that to authorities. “One police officer in our study suggested that rights activists are crucial to counter-extremism initiatives because they ‘fill in the gaps where police can’t go,’” they wrote. (This, of course, depends on police having a trusting relationship with marginalized communities—a reality that seems quite distant today.)

But funding remains an issue. Russell is currently fighting to keep Speqtrum going not only during a pandemic, but as the organization’s provincial funds are set to run out.

A community hub space, first proposed by councillor Nrinder Nann, has received support from council. Mayor Eisenberger and several staff and councillors even visited Toronto’s 519 community centre, looking at it as a potential model for a centre in Hamilton. A community hub, however, was not in this year’s city budget, which passed before the COVID-19 pandemic began. (A city spokesperson said that as the city begins to reopen, “this important work will continue.”)

But the fight is far from over. “I think sometimes people don’t realize the amount of stress that this puts on people in our community,” says Russell. “The hate stuff is happening at the same time as our communities are hurting.”

“I think it’s incredible how resilient we’ve been able to be,” she adds. “But building these spaces, building community, takes a lot of time and energy and a lot of heart.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra