Editor’s note: This explainer includes descriptions of violence against Black and Indigenous folks and people of colour.

“No justice, no peace!”

“Black Lives Matter!”

“Say his name: George Floyd.”

These are just some of the rallying cries heard at protests across North America and abroad in the past month, as a movement to put an end to systemic and institutional anti-Black racism and police brutality gains steam. After the murder of Floyd, a 46-year-old father of five, at the hands of police in Minneapolis, Minnesota, in May, hundreds of thousands took to the streets to call for change.

But among protesters, one cry stands out: Defund the police.

While the call to defund police is a new concept to some, it’s been supported by Black, Indigenous, racialized and LGBTQ2 activists and allies—in varying interpretations—for decades.

Here’s everything you need to know about defunding the police.

What exactly does it mean to defund the police?

At its root, defunding the police means removing the power police have in our society.

Since increased calls for the defunding or abolishment, several cities and organizations have decided on their own ways to “defund” police. In one of the most high-profile examples to date, the Minneapolis City Council announced in June that it intended to dismantle and defund the police to re-evaluate emergency response and public safety measures in the city—a direct response to the police killing of Floyd.

But what replaces the police? The Minneapolis resource group MPD 150 argues that the money that balloons police budgets should instead be redirected to systemically underfunded social and community resources and invested in prevention, not punishment.

Why defund the police?

In the U.S., Floyd’s death represents nothing new. This year alone has been particularly deadly for Black Americans: In March, 26-year-old EMT Breonna Taylor was shot and killed by police while asleep in her home in Louisville, Kentucky. Floyd was killed by Minneapolis police in May, sparking mass protest. And earlier this month, a white Atlanta officer shot and killed 27-year-old Rayshard Brooks, who fell asleep in his car in a fast-food drive-thru. These are just three of the many killings of Black Americans by police in the first six months of 2020.

Chantel Moore’s mother Martha Martin, centre, participates in a healing walk from the Madawaska Malaseet reserve to Edmundston's town square honour Moore in Edmundston, N.B. Moore was a 26-year-old Indigenous woman who was fatally shot by police in Edmundston. Credit: The Canadian Press/Stephen MacGillivray

In Canada, police brutality endangers Black and Indigenous lives, too. Most recently, police in Edmunston, New Brunswick, shot and killed 26-year-old Chantel Moore, during what was supposed to be a wellness check after they received reports of concerns that she was being harassed. Pending results from an investigation into her death, initial reports show police didn’t use any non-lethal de-escalation measures before shooting. And in Toronto, 29-year-old Regis Korchinski-Paquet fell from her 24th-floor balcony after police were called during a mental health emergency—only she and police were in her unit at the time. Her death is currently being investigated by Ontario’s Special Investigations Unit.

Several other people experiencing crisis have also recently been killed by police: Rodney Levi, a 48-year-old man from the Metepenagiag First Nation in Red Bank, New Brunswick, was tasered, shot and killed by police while experiencing a mental health crisis. And 62-year-old Ejaz Choudry in Mississauga, Ontario, was killed by police during a similar crisis call.

For LGBTQ2 people, relationships with police have also long been fraught. Police have historically criminalized queer and trans communities—from raiding bathhouses to arresting trans sex workers. Pride was born out of a protest against police, after police raided the Stonewall Inn in New York City in 1969. Black and Indigenous queer and trans people are also at a higher risk of criminalization. Several Black trans people have been murdered in recent months, including 38-year-old Tony McDade, who was shot by police in Florida.

This history has led to calls, particularly from Black Lives Matter chapters, to ban uniformed police contingents, cruisers and floats from Pride parades. In 2016, Black Lives Matter Toronto held a sit-in during the parade, calling for a more inclusive festival, starting with the ban of uniformed police from the parade. Those calls have extended to elsewhere in Canada and the U.S.—a small step toward justice for decades of police mistreatment against LGBTQ2 people.

In Alex Vitale’s 2017 book The End of Policing, the sociology professor writes that police are being tasked to go too far beyond their scope. They play the role of social workers, they’re in schools, they deal with untreated mental illness and more. In fulfilling roles they are not equipped to deal with, they’re using the tools provided to them: guns, handcuffs, batons, riot gear. That often leads to violence, especially toward Black, Indigenous and other marginalized people.

So why not reform the police instead of defunding them?

Police have had more than enough chances to reform: In Canada, the 2015 Truth and Reconciliation Commission provided guidelines for better relationships between Canada and its Indigenous populations. After the killing of 45-year-old Andrew Loku, a Toronto man who was shot and killed by police in his apartment building, a 2017 coroner’s inquest offered 39 recommendations to challenge anti-Black racism in the city’s police force. And, most recently, the 2019 Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls and 2SLGBTQQIA people called for changes to the Canadian justice, courts and policing systems based on the lived experiences of survivors, intergenerational survivors and families, as well as input from experts and Knowledge Keepers.

These recommendations provided concrete, here’s-what-you-can-do actions. But the statistics surrounding police brutality and Black and Indigenous people in Canada continue to paint a troubling picture.

Protesters demonstrate in front of a townhouse owned by Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin, in Florida. Chauvin was one of four officers charged with the murder of George Floyd. Credit: AP Photo/Phelan M. Ebenhack

In Toronto alone, Black people are 20 times more likely to be injured or killed by police, based on a 2018 Ontario Human Rights Commission report on race and policing. Meanwhile, Indigenous people consistently represent more than 50 percent of deaths by police in Manitoba and Saskatchewan.

“Abolishing the police means the end of their violence, by definition,” says Desmond Cole, a Toronto journalist, activist and author of The Skin We’re In: A Year of Black Resistance and Power. “If you’re not calling to abolish the police and stop their violence, what do you intend to achieve through a [budget] reduction?”

“The specific tactics police used to harm us, remain unchallenged,” he adds. “If you’re not going after the police’s licence to kill under the laws, and their ability to do so through their weaponry, you can talk about funding all you want and it’s not going to make a difference.”

What does defunding the police actually look like?

In Minneapolis, where the majority of the city council announced a plan to disband the city’s police force, the police department could be completely re-envisioned in the coming months. “It is clear that our system of policing is not keeping our communities safe,” Lisa Bender, council president, told the Associated Press.

Minneapolis wouldn’t be the first American city to overhaul its police force. In 2013, Camden, New Jersey, disbanded its police department, redefining the role of officers to act more as “guardians” than “warriors” of the city. Police focused on community outreach and de-escalation tactics in place of excessive force. The overhaul wasn’t perfect—the number of summonses over small offences, like broken car lights or riding your bike without a bell, increased. And the force still remains overwhelmingly white in a predominantly Black city. But in 2012, Camden was ranked one of the most dangerous cities in the U.S.; by 2019, crime rates had fallen more than 60 percent.

Here in Canada, a Hamilton public school board recently scrapped a school policing program, noting that they’ve received several messages that the program creates fear and anxiety among Black and Indigenous students.

The Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH) in Toronto recently pointed out that police take on work they are not trained for, calling for the removal of police from the frontlines of those in crisis. “For too long, the healthcare system has relief on police to respond to mental health crises in the community,” a statement from CAMH reads. Currently, in Toronto, mobile health teams consist of a nurse and a police officer, but these teams only provide secondary services, leaving police alone as first responders.

The city is taking its own avenue: A motion will be put forward at the next city council meeting to defund the Toronto Police Service by 10 percent—a reduction of its budget by $122 million—supported by councillors Josh Matlow and Kristyn Wong-Tam. The motion moves to put money into childcare, affordable housing and community-led alternatives to policing.

“Would a situation like Regis [Korchinski-Paquet]’s escalated by having trained professionals who are, whether they be social workers or psychologists who are not in a uniform with a gun…arriving at that door? We need to try and answer what happened to Regis but also how can we serve people better,” Matlow said.

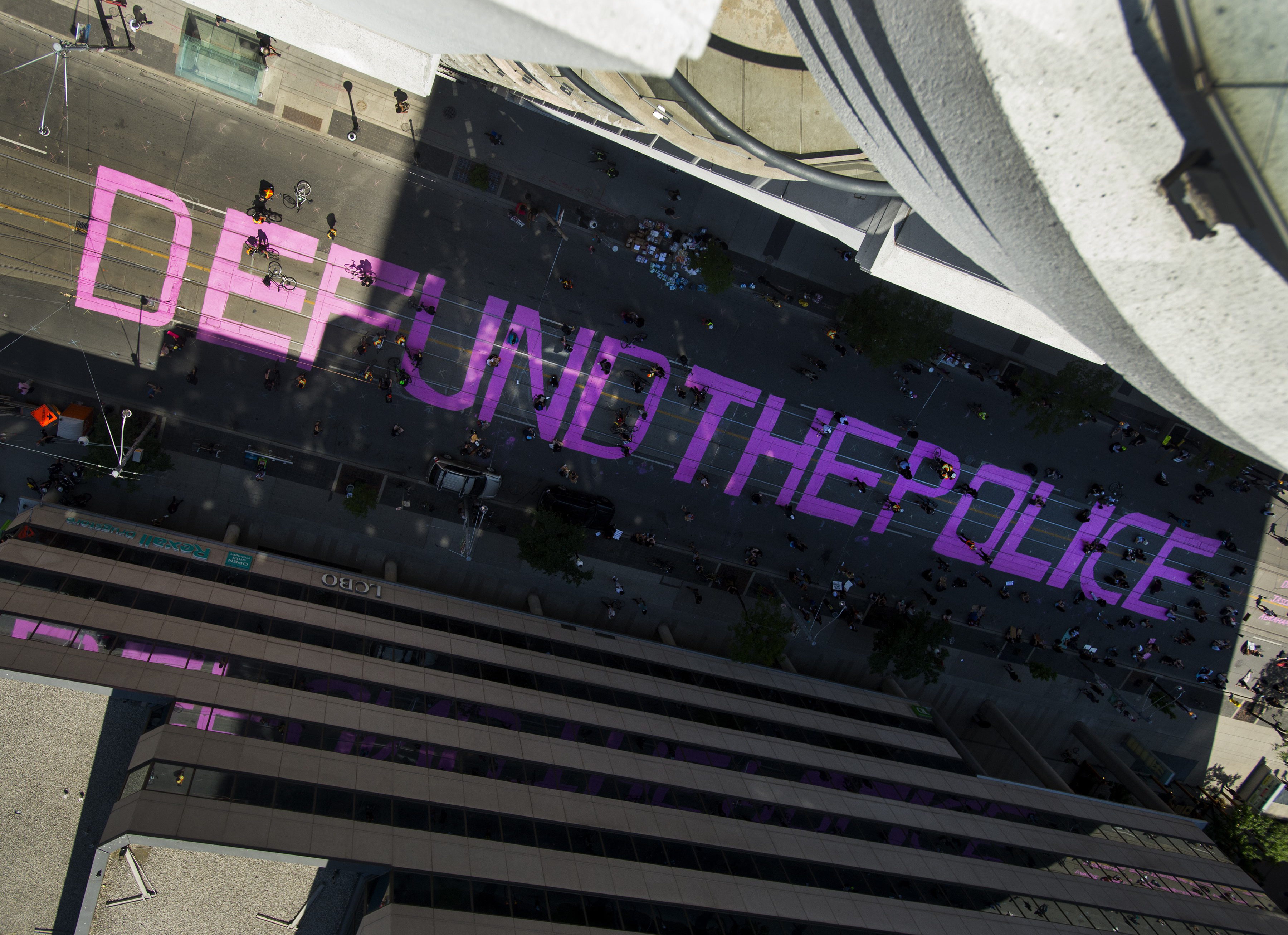

Protesters in Toronto painted the words "defund the police" in front of police headquarters, June 19, 2020. Credit: The Canadian Press/Nathan Denette

Mayor John Tory, who previously stated he did not support “arbitrary cuts” to police budgets, put forth his own motion to council “to develop alternative models of community safety response” for incidents where a non-police-led response to mental health crises is appropriate or “where a police response is not necessary.”

The main hurdle facing these motions is the province: The Police Services Act of 1990 doesn’t give the city line-by-line control of the police force’s budget. Ontario Premier Doug Ford, meanwhile, has dismissed the councillors’ motion, saying, “I don’t believe in that for a second.”

And Cole points out that the motion leaves some cards on the table. “It doesn’t address the problem that people are in the street crying for: death, arrest, surveillance…the specific tactics that police use to harm us are left unchallenged by this motion.”

Are all of the communities affected by police violence and brutality on board with this method of defunding?

Not exactly. Others think a simple re-allocation of funds is not enough, and alternatives to defunding the police don’t look the same for everyone.

Increased reliance on social workers has historically not been the solution for Indigenous communities, for example. Social workers, along with police, were largely responsible for the apprehension of Indigenous children during the residential school era and the Sixties Scoop. In the North, RCMP were involved in forcibly relocating Inuit communities as a way for the Canadian government to assert physical sovereignty over the North in the early 1950s. Today, Indigenous children are still largely overrepresented in the child welfare system, despite federal legislation planning to move control of child welfare to Indigenous communities themselves.

Alex Vitale argues changes to policing are not as simple as flipping a switch. “I think this will look like a series of local budget battles,” he said in a recent interview with NPR. “And that’s really what’s going on across the country when we have these divest campaigns in places like Los Angeles and Minneapolis and New York and Durham, North Carolina, and Nashville, Tennessee, and Dallas, Texas.”

“These are folks who are saying concretely, ‘We don’t want police in our schools. We want that money spent in ways that help our children, not criminalize them. We don’t want more money for overtime for narcotics officers. We want actual drug treatment programs, safe injection facilities, things that will help people.’”

How can I relearn what public safety looks through the lens of defunding?

Throughout conversations about defunding police, general public safety frequently comes up. What happens, say, in the case of a robbery?

Advocates of divestment note that many police forces haven’t historically been effective at solving or preventing crime. A New York Times story found in a sample of three American police departments, officers spent most of their time responding to non-criminal calls and traffic complaints—issues that could be dealt with by non-uniformed officers or civilians. And as Sandy Hudson, one of the founders of Black Lives Matter Toronto, writes in HuffPost, when it comes to violent crime, police long failed to catch serial killers Robert Pickton in Vancouver and Bruce McArthur in Toronto; in both cases, victims were from marginalized communities. Sexual assault cases, too, are underreported to police, and in the few cases that do get reported, rarely do survivors see justice.

Demonstrators protest at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, over the police killing of George Floyd. Credit: AP Photo/Alex Brandon,

It’s a long process, but resources like Minneapolis’s MPD 150 instead promote prevention over punishment. “There are other ways to think about ‘safety’ than armed paramilitary forces with a proven track record of racism, brutality and a focus on responding to harm after it’s happened rather than de-escalating or preventing it in the first place,” they write.

But defunding is not the be-all and end-all, right?

In the conclusion of Vitale’s book, he argues that only a large shift in the world of policing, and quite possibly the world, will be needed to truly change. “As long as the basic mission of the police remains unchanged, none of these reforms will be achievable,” he writes. “Institutional imperatives of the politically motivated war on drugs, disorder, crime, etc., would win out. Powerful, political forces benefit from abusive, aggressive and invasive policing, and they are not going to be won over or driven from power by technical arguments or heartfelt appeals to do the right thing.”

In the meantime, Cole encourages people to start talking about defunding the police in their own circles, pushing the conversation to address systemic white supremacy.

“Even if we’re able to abolish police, all of our institutions of government will still be sites of systemic racism,” he says. “Abolition is a mindset rather than a set of policies. Removing the conditions that make us believe prisons are necessary, that make us believe the current child welfare system is a norm—it’s challenging that. What makes us believe that certain kinds of violent interventions are themselves inevitable for human existence.

“Abolishing the police is not going to address the imperatives that the state puts forward to justify its own violence. We really have to go deeper.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra