On June 28, 1969, police raided the Stonewall Inn, a mafia-owned bar in New York’s West Village frequented by LGBTQ2 people. Queers of the era were used to bar raids like this; usually the police would storm in, card and arrest patrons, dump the liquor, get their payoff from the owners and leave. A few hours later, the bar would be back up and running, having replenished the liquor stock from a nearby stash (often a parked car down the block). But, on that night in 1969, gay, lesbian, bisexual and trans people tore up the script. They fought back and changed history forever.

There is much lore surrounding what exactly happened that evening and the several that followed. Those who were there recall a sense of collective rage as the cops dragged people from the bar. It’s been said a brick was thrown (in some accounts, it was a shot glass), and the situation quickly escalated into a riot. In one of the night’s most celebrated moments, drag queens defied the cops with uproarious Rockette-style kick lines down Christopher Street.

For five more nights, torrents of pent up rage continued to flow out as more LGBTQ2 people took to the streets. A year later, inspired by the uprising, activists organized the first ever Gay Pride March from Greenwich Village to Central Park. Former Village Voice reporter Lucian Truscott IV said in a 2011 documentary that Stonewall was a turning point from which “the system of oppression of gay people started to crumble.” Artist Thomas Lanigan-Schmidt, who was at Stonewall, called it “a ghetto riot on home turf.”

Over the years, the Stonewall riots have come to be seen as the pivotal moment in the modern queer rights movement, their legacy resonating far beyond the West Village — one of Britain’s largest LGBTQ2 rights groups is named Stonewall, and each summer Christopher Street Day is celebrated in Berlin. This summer’s Pride events will mark the 50th anniversary of the uprising with Stonewall commemorations around the globe. Pride Toronto will honour both Stonewall’s anniversary and the 50th anniversary of the partial decriminalization of gay sex. Two universities in Paris will host an academic conference titled Stonewall at 50 and Beyond, and New York City will celebrate World Pride: Stonewall 50, a month-long festival that will draw hundreds of thousands of tourists clad in rainbow flags.

With the diversity within LGBTQ2 groups, how will our communities tell the history of Stonewall? Acts of commemoration, after all, involve critical choices about which lives, voices and stories are included in the canon. In NYC, artists, activists and historians are coming up with radical and ingenious ways to commemorate Stonewall. At a time when our hard won rights seem increasingly fragile, especially for people of colour, trans folks and other disenfranchised groups, the battle at the Stonewall Inn — and the battle over its history — has never felt more important.

The events of Stonewall became the subject of debate and myth-making almost as soon as they happened. Trans activists Sylvia Rivera and the late Marsha P Johnson are often credited for helping instigate the uprising. Many, in fact, have said it was Johnson who threw the first brick. (Johnson herself said she didn’t arrive at the bar until rioting was well underway.) But their role in the fight, and the role of other trans and queer people of colour who were there that night, was not always recognized or celebrated.

In fact, soon after the riots, Stonewall was subsumed under the greater narrative of gay rights — a movement largely defined by, and focused on, gay, cis, white men, and credit for the seminal event was often claimed by them. At the 1973 Gay Pride Rally in New York City, Rivera denounced a mostly white, cis and male crowd for not fighting for the release of imprisoned trans folks who she said threw the first bricks at the uprising. Initially, the crowd was bewildered. Eventually, they booed and jeered until she was forced off the stage. (It was just announced that Rivera and Johnson will be honoured with their own monument in Greenwich Village.)

Other remembrances have been just as fraught. The first monument to the riots in New York is located in Christopher Park near the bar. Dedicated in 1992, The Gay Liberation Monument includes the work of renowned (and heterosexual) sculptor George Segal and depicts four figures (two women and two men) cast in bronze and covered in white lacquer. In 2015, anonymous activists painted the figures brown and dressed them in wigs, a scarf and bras. Echoing Rivera, the activists left behind a sign reading, “Black and Latina trans women led the riots. Stop whitewashing.”

"Gay Liberation" by George Segal, Christopher Park in New York City, NY Credit: Gay Liberation monument flickr photo by tedeytan shared under a Creative Commons license;

That same year, Roland Emmerich’s feature film, Stonewall, focused heavily on the trials and backstory of a fictional cis white gay man from rural Indiana; in the movie, he is the one portrayed as throwing the symbolic first brick. The scene has been interpreted by many as minimizing and erasing trans, lesbian and POC activists like Rivera and Johnson, as well as Stormé DeLarverie, a Black lesbian and drag king who recalled fighting a cop during the raid at the bar. Stonewall veteran Miss Major Griffin-Gracy said in an interview about the film for Autostraddle: “Here was our history, a history made real by Black and Brown trans women and lesbians, but it was a false, whitewashed and cis-washed version.”

The question of who threw the first brick (or shot glass or high heel, as other accounts describe) has been central to many of the debates surrounding Stonewall’s history. So much lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans history has been lost over the years that these better known moments of resistance, bravery and triumph take on extra weight. And for those who continue to be the most marginalized — as well as the least celebrated and represented in our official narratives and popular culture — the act of affirming one’s rightful place in these histories is powerful. Claiming first-brick-throwing status is not only a matter of acknowledging one’s champions and heroes in the queer and trans lineage, but it is also a means of asserting one’s humanity in the present day.

Given the current state of queer and trans politics, there’s no question that these debates will continue. But some activists, artists and historians believe focusing on the seemingly unanswerable and perennially fraught question of who threw the first brick has prevented us from realizing more radical histories of Stonewall — histories that could inform today’s generation of activists.

Sarah Schulman is an author, activist, academic and one of the co-founders of New York City’s Lesbian Avengers, an activist group that organized NYC’s first Dyke March. She recognizes the roles played by more marginalized folks in the Stonewall uprising as well as the gains made in certain areas in the ensuing 50 years, but she’s concerned about dwelling on single moments of action instead of acknowledging sustained, collective activism.

Over the phone, she tells me the “first brick” debate can make “vanguardist impositions” over history. Photographs of the riots show the diversity of the people who participated: trans people of colour, gay men, lesbians, drag queens, sex workers and homeless hustlers, among others. The important point to emphasize, Schulman says, is how a diverse group of people who were sometimes at odds with each other united in that specific moment to achieve a common goal. It’s this type of historical narrative that can provide a useful road map for today’s activists who are looking to build effective political movements.

Avram Finkelstein, another longtime New York-based artist and a founding member of the AIDS activism group ACT UP, agrees that our conversations about Stonewall tend to emphasize the actions of heroic individuals over collective struggle. He is hopeful, though, that as the 50th anniversary approaches, our communities can talk about history differently. “Our radical queer mind is ingenious, dogged, anti-hierarchical, persistent and resourceful,” he says.

And, indeed, many activists, archivists and artists in NYC are creating radical histories of the uprising. These contributions place trans folks and people of colour in the foreground and they compel us to reckon with the messiness of history — including the multiple narratives and myths about Stonewall that continue to circulate in our communities.

Chris E. Vargas is the founder of the Museum of Transgender Hirstory & Art, also known as MOTHA, which takes an ephemeral and experimental approach to recounting the past by holding pop-up performances, exhibitions and panels. Unlike a traditional museum, MOTHA has no permanent physical location. Recently, Vargas asked a group of intergenerational artists to propose replacements for the official monument commemorating Stonewall in Christopher Park.

The result was an exhibition called Consciousness Razing: The Stonewall Re-Memorialization Project, which was housed on the fifth floor of NYC’s New Museum. It consisted of a miniature model of Christopher Park at a 1:7 scale, cast in spectral white, and placed 12 re-imaginings of Segal’s monument together as a kind of historical commemoration funhouse.

Consciousness Razing was clever in how it diversified our narratives of Stonewall — but its real genius is that it didn’t allow any one of them to become the single historical truth. When I asked Vargas about this, he said there can be conflicting realities, but that’s not to say that each one isn’t true. Vargas believes holding space for multiple historical narratives forces us to entertain uncertainty about the “facts” — which he doesn’t see as a bad thing but rather an opportunity to expand upon the idea of a single, official history.

Finkelstein has also been imagining how to commemorate the history of Stonewall. For many years, he’s found Segal’s official monument lacking. Its colourless, still-life format fails to capture Stonewall’s intense political and sexual energy. He also found it exclusionary of people of colour and trans folks. So, two years ago, he and his friend Hugh Ryan, a historian and author, created the Squatting on Stonewall project.

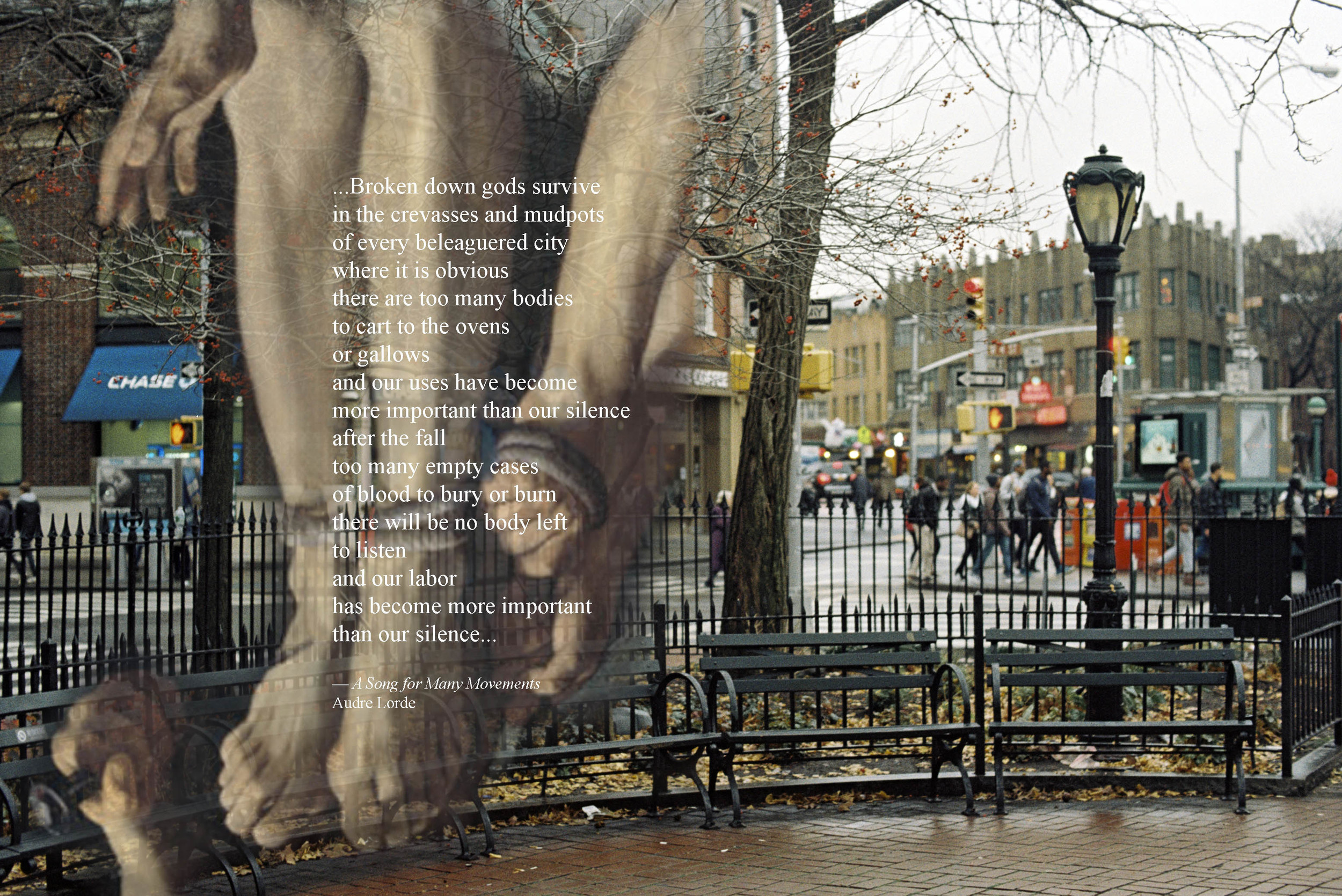

Like Vargas, Finkelstein and Ryan commissioned a diverse group of artists to engage with Segal’s monument. Using only photographs, these re-imaginings directly challenge the history represented by the monument through acts of imagined vandalism, graffitiing or outright destruction. Take Carlos Motta’s work: in it, the white-painted figures are completely erased. Instead, there is an assemblage of spectral and bound brown bodies upon which is superimposed an excerpt of Audre Lorde’s poem A Song for Many Movements.

“When I think about the Gay Liberation Monument at Christopher Park I think of silence... And I think about the failure to memorialize the lives of the victims of institutional abuse on our own terms.” Carlos Motta about his work Untitled, featured in Ten Queer Reimaginings of New York's 'Gay Liberation Monument. Credit: Courtesy Vice;

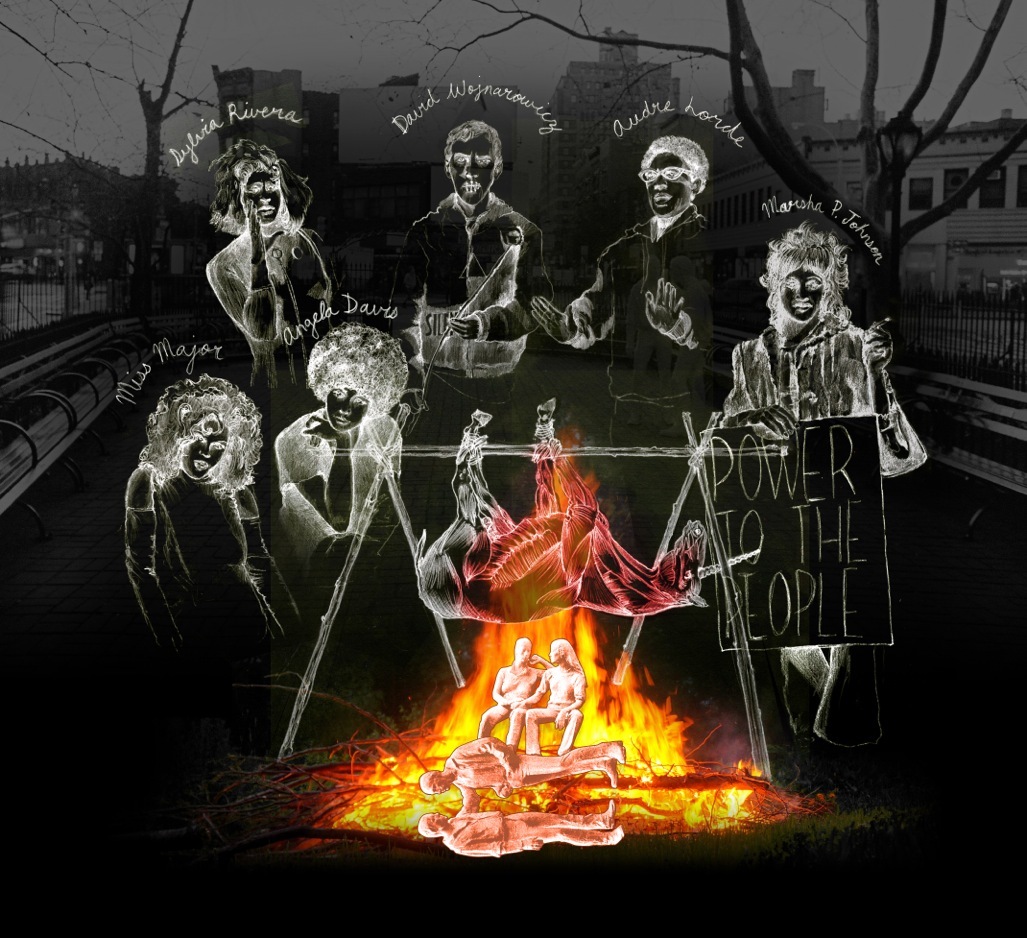

And then there’s Fire Starters at the Unicorn Roast (What Happened to the Queer Radical) by Montreal-born trans artist Cassils. In the piece, a group of trans, POC and radical queers use the Segal monument as firewood to roast a skewered unicorn over open flames. There’s nothing subtle about it: in this combustible and dramatic commemoration, the established narrative of Stonewall becomes fuel for a more radical and inclusive vision of history.

Cassils’ provocative work skewers gay history as we know it. Work featured in Ten Queer Reimaginings of New York's 'Gay Liberation Monument.’ Credit: Courtesy Vice;

What Vargas, Finkelstein and Ryan’s projects have in common is their desire to give nuance to discussions about Stonewall’s history, telling a more expansive and complex narrative of the past, beckoning us to adopt more radical and inclusive politics in the present. Their work recalls author Thomas King’s insightful dictum about the power storytelling has to shape our world: “If you want a different ethic, you must tell a different story.”

But beyond works in museums, monuments in parks and public art, how else will queer and trans folks commemorate the legacy of the Stonewall riots this summer?

It’s often forgotten that the first-ever Pride parade in NYC was held as a way to mark the first anniversary of the riots. Fifty years on, Pride parades around the globe are often still a site of community protest — a living, breathing instance of the spirit of rebellion central to the historical events of Stonewall.

In 2016, a few hundred kilometres away from NYC, the Toronto chapter of Black Lives Matter (BLM-TO), halted the city’s Pride parade for 30 minutes to secure anti-racism commitments from the organizers as well as the removal of police floats and booths from Pride events. The parade resumed after Pride’s then-executive director Mathieu Chantelois agreed to BLM-TO’s nine demands and hugged the chapter’s co-founder Rodney Diverlus. “Even though we are celebrating Pride, and giving folks the opportunity to live their life, there’s still a group — black folks and people of colour — who are still very much criminalized for their queerness and are not safe,” Alexandria Williams, a co-founder of BLMTO, told Xtra before the parade.

Pride Toronto released a statement saying it will agree to all of Black Lives Matter's demands. Credit: Nick Lachance/Xtra

By all measures, BLM-TO’s protest was a success. They have systematically tracked the progress of the demands they made in 2016 and, according to the list, they have secured all of them, including a doubling in funding for the Blockorama Stage (which highlights Black queer and trans artists) and prioritizing the hiring of Black trans women, Indigenous people and others from vulnerable communities. These points are impressive expansions of justice in LGBTQ2 communities in themselves, but what BLM-TO’s checklists can’t capture is how their 2016 protest reminded queer and trans folks around the world of the political possibilities of Pride celebrations.

Over the years, Pride’s potential as a place to sow the seeds of dramatic social change has been obscured by creeping corporatization. Beginning in the early 1980s, Pride celebrations in major cities, including Toronto, began to sell advertising and accept sponsorships. At first, only LGBTQ2 businesses were allowed to advertise. Today, large companies like TD Bank, Bud Light, Fido and Lyft sponsor the celebrations in order to reach what they believe is an “influencer demographic.”

Government support of Pride events in Canada has followed a similar trajectory: municipal, provincial and federal governments all make sizable monetary contributions to Pride festivities. This year, the federal government announced a special one-time grant of $450,000 to Pride Toronto to help improve relations between LGBTQ2 people and the criminal justice system.

The result is that many Pride celebrations are now dependent on that support, and the cost of that dependence is the dilution of Pride’s original purpose and political edge. It’s no wonder that young queers attending Pride are often unaware of its roots — we have allowed the festival to move further and further away from the history of protest and rebellion it’s supposed to help us remember.

New York activist Sarah Schulman sees ample reason to question Pride’s current format — she recalls organizing the original NYC Dyke March with no corporate sponsors or permits. Given Pride’s history as a protest against police and government suppression, she can’t understand why queer people have allowed governments and corporations to have so much control over contemporary celebrations.

In recent years, queer and trans communities have begun to respond to the over-corporatization of Pride. In NYC, a group called the Reclaim Pride Coalition publicly called the city’s official Pride celebrations “a bloated, over-policed circuit party, stuffed with 150 corporate floats.” The group says the festivities no longer “represent the ‘Spirit of Stonewall’ on this 50th anniversary year of the 1969 Stonewall rebellion.” It will protest the official parade with an unsanctioned alternate march from Greenwich Village to Central Park, the route of the very first parade. There is talk of a similar march in Washington, DC.

As we move towards Stonewall’s 50th anniversary, many others are thinking of ways to commemorate it through protest and dissent. “Trust me,” Finkelstein says, “for every rainbow flag, there will be someone doing something that will be provocative or that will pierce the dominant narrative with counter-narrative.” When asked how queer and trans people can do justice to Stonewall’s history, he says: “Start another riot.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra