Thomas Mann’s 1912 novella Death in Venice contains one of the most famous scenes in gay literature. The protagonist is famous writer Gustav von Aschenbach who is suffering from writer’s block and goes to stay in the Grand Hôtel des Bains in Venice.

One night at dinner, the 50-something Aschenbach is alone in the dining room, waiting for dinner to start when he notices a Polish family at a nearby table. And, more to the point, the aristocratic family’s young son, Tadzio.

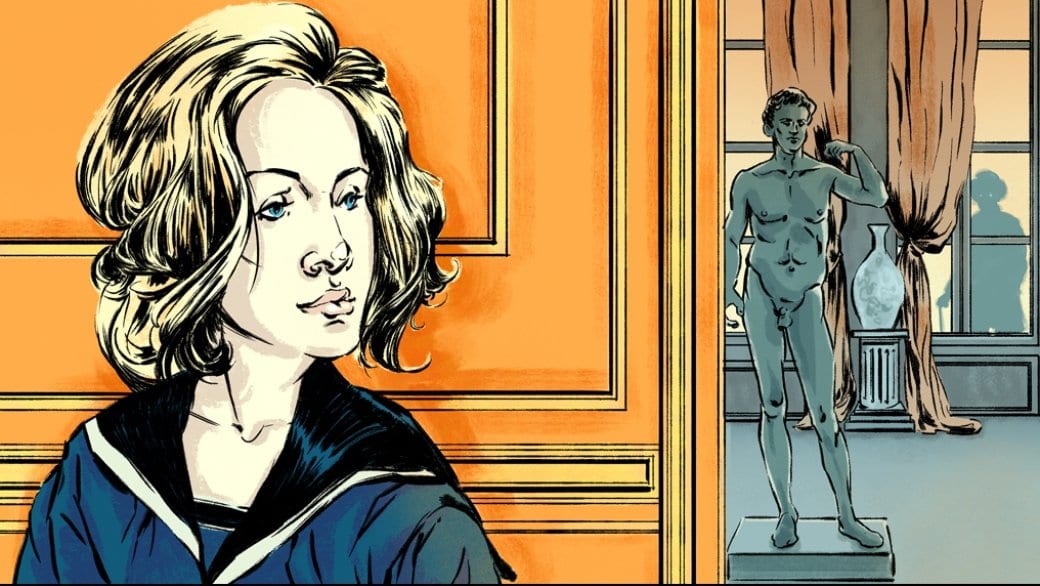

Aschenbach noticed with astonishment the lad’s perfect beauty. His face recalled the noblest moment of Greek sculpture—pale, with a sweet reserve, with clustering honey-coloured ringlets, the brow and nose descending in one line, the winning mouth, the expression of pure and godlike serenity.

Advertisement

And his inward rhapsodizing goes on from there. Aschenbach is immediately entranced by the beautiful 14-year-old youth, who is wearing an English sailor suit. Over the course of his stay at the hotel, he never touches or speaks to the boy, but begins watching him and following him around, obsessed (a typically neurotic Mann protagonist, which was also a character trait associated with the German author).

Aschenbach becomes so obsessed that he puts himself in danger, refusing to leave Venice even as a plague — a cholera epidemic — descends upon the city.

Mann’s novella has since been made into an opera, a ballet and the 1971 film of the same name, directed by Luchino Visconti and starring the gorgeous Björn Andrésen as Tadzio.

The book has become a staple of gay literature for a variety of reasons — because of its homoeroticism, because it was an early work to deal with same-sex attraction, and, at least for those aware of the fact, because of Mann’s own homosexuality.

The Nobel Prize-winning Mann had a wife, but as his diaries eventually revealed, he had difficulty dealing with his attraction to other men (or rather, boys, for the most part). And his homosexuality (or perhaps bisexuality) is also evidenced by the subject matter of some of his works of fiction — Death in Venice being the most famous example.

Mann’s homosexuality is also evidenced by the fact that the novella is based mostly on fact. Mann himself travelled to the Grand Hôtel des Bains in Venice in the summer of 1911, and became fascinated by a gloriously beautiful boy he first noticed in the hotel dining room on his first evening. There was also a cholera scare, though there are some significant differences between the book and reality as well, including the fact that Mann was actually 36 and the boy was 10, and Mann’s wife, who was also on the trip, claimed he didn’t follow the boy around, but that “the boy did fascinate him.”

So, who was the real Tadzio? Who was this real-life boy who Mann saw and made into such an important figure in gay literature and gay culture, almost a symbol of unrequited love and love between the generations?

Gilbert Adair traces the life of the real Tadzio in the aptly named 2001 mini-biography, The Real Tadzio.

For starters, the boy Mann saw was not named Tadzio, but Adzio (short for Wadysaw) Moes. He was born in 1900 in southern Poland to Baron Aleksander Juliusz Moes and Countess Janina Miczyska. His wealthy, aristocratic family owned several factories in Poland and lived in a grand manor in a place called Wierbka.

Adzio Moes’ family was staying in Venice that summer because a doctor had (in typically olde thyme doctor fashion) prescribed sea breezes and play for Moes’ chronic lung issues.

Adair writes that Moes, who by all accounts was heterosexual, was often the centre of attention, and really milked it, even as a young boy. Mann may have first caught sight of the boy making a grand entrance into the dining room to show off a pair of new shoes he was particularly proud of. Later in life, Moes said he recalled that an “old man” stared at him wherever he went that summer in Venice.

Growing up at the time and in the place that he did, Moes lived a violent and eventful life. He was a sub-lieutenant in the Polish-Soviet War (a conflict that ran from 1919 to 1921), earning him a medal for valour under fire. In 1939, when the Nazis invaded Poland, Moes mobilized as a reserve officer and was captured and sent to a German prisoner of war camp for six years.

When the camp was liberated by the British in 1945 after the Second World War ended, he returned to Poland only to find that the newly installed communist government had confiscated all of his family’s businesses and wealth (a fate suffered by most of the rest of Poland’s wealthy as well), and outlawed his hereditary title of baron.

The impoverished but well-educated Moes had a series of jobs over the years following the war, including working as an interpreter at the Iranian Embassy in Warsaw. Moes and his wife lived in a small apartment until they had worked and saved enough to buy a small bungalow in 1954.

Life would gradually improve in Poland (though it would never again be like the good old days), but because of his aristocratic background he was under nearly constant surveillance by the communists for most of the rest of his life. They also repeatedly tried to persuade Moes to act as their spy at the embassy where he worked (being anti-communist, he refused).

Mann’s book, originally written in German, was published in many languages, including Polish, but Moes didn’t become aware of his contribution to the book until 1924. Moes’ cousin read it and noticed some parallels and brought it to Moes’ attention. Moes doesn’t seem to have cared much about it, probably too busy being rich and handsome and running the factories he’d taken over from his ailing father.

When Visconti’s film adaptation was released in 1971, Moes took a greater interest. Then in his 70s, he watched it while on a trip to Paris (the communists had relaxed travel restrictions a bit by then). He doesn’t seem to have minded being portrayed in the book and subsequent film, and the film’s release sparked a surge of nostalgic letter writing between Moes and old friends and relatives.

In the film, there’s a scene where there receptionist at the hotel says the name “Moes.” Suddenly, the world knew who the real Tadzio must have been, and German journalists visited Adzio Moes in Poland (and of course the communist party sent police cars to linger outside his small house for the duration of the visit).

Moes died in 1986 in Warsaw. A few years before he died, he planned to finally revisit Venice — to bring his life full-circle, in a sense. Unfortunately, he wasn’t able to make the trip. By some amazing coincidence, Venice was once again in the grip of a cholera scare.

History Boys appears on Daily Xtra on the first and third Tuesday of every month. You can also follow them on Facebook.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra