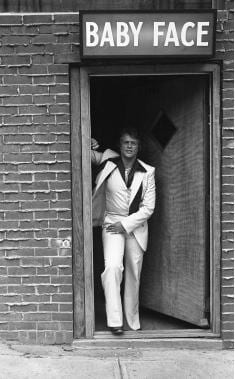

Credit: Suzanne Girard photo

The last few weeks I’ve been trying to track down an elusive Montreal legend: Denise Cassidy, better known as Babyface. Cassidy inherited the nickname from her brief wrestling career before she opened Montreal’s first lesbian-only nightclubs.

Between 1968 and 1983, Cassidy managed La Source, La Guillotine, Baby Face Disco, Chez Baby Face and — after Quebec’s French language law, Bill 101 — Face de bébé.

While the essay “Remembering Lesbian Bars in Montreal” from the 1993 book Gay Studies from the French Cultures, edited by Rommel Mendes-Leite and Pierre-Olivier de Busscher (Routledge Books), documents Montreal lesbian spaces between 1955 and 1975, it was Cassidy who opened the city’s first lesbian-only bars.

“I’ve done everything in the business,” Cassidy told Montreal’s Hour newspaper in 1996. “I started as a busgirl in the Ponts de Paris on St-Andre [Street] and then as a waitress at the mixed gay bar La Cave. I ended up as a boss with my own licence.”

That Hour interview with Cassidy was done by Université de Montréal à Québec professor Line Chamberland, who told me last week she’d lost all contact with Cassidy some years ago. “I believe Cassidy [an anglophone from Shawinigan] came to Montreal in 1955,” Chamberland says.

Cassidy’s “official” photographer in the 1970s and 1980s was Suzanne Girard, today a Montreal CEGEP professor and co-founder and director of Montreal’s famed Divers/Cité Festival. “I think she moved to Florida many years ago,” Suzanne tells me.

In other words, today the reclusive Cassidy is either alive, in her mid-70s and enjoying the sunshine in Florida, or she’s dead.

So Line Chamberland’s interview with Cassidy — originally published in the French gay publications Revue Treize and Fugues before I translated it into English for Hour 15 years ago — is, as far as I know, the only interview with Cassidy ever published.

Cassidy’s bars became well-known throughout the United States and Europe. “It was difficult to be accepted by girls from [Montreal’s mostly English] West End,” Cassidy told Chamberland. “I came from the [mostly French] East End, I was more or less butch, and I wore gold lamé. Girls in the West End didn’t have the same mentality; they were more snobbish — it wasn’t a butch and a femme, it was two femmes. But once my name was established everything was okay.

“I also ran my club differently. Unlike other clubs, the girls couldn’t do whatever they wanted. The law was the law. I was strict, but I was always respected.”

Cassidy’s bars protected lesbians from harassment. She also avoided underworld intrigue — the Montreal mafia demanded protection money from establishments throughout the city in those days — and prevented police raids by maintaining a “clean” establishment.

“The girls were scared to come [to my bars at first]. They weren’t out like they are today and they were afraid their families would discover what kind of bars they went to.

“The first bars were pretty tough — it was a hard milieu, especially when men discovered my bars were for women only. There were always men who wanted to come in. I worked with a baseball bat by my side for the longest time. And there were fights. Friday night was hell sometimes!”

The brawls weren’t just between drunk men picking fights; sometimes it was her paying customers as well.

“They [the girls] would come in alone, have a few drinks and let loose. I tried to get there before the fights broke out. I kept an eye on everything, although Saturday nights were quieter since they were mostly couples.”

All the women I talked to for this column, including Suzanne Girard and Line Chamberland, remember Cassidy and her bars fondly. But the end was near after the language wars, fuelled by the 1980 Quebec referendum. Cassidy closed Face de bébé in 1983.

“It was impossible to mix the West [End girls] with St-Denis [Street, where Face de bébé relocated] — the English [versus] the separatists. [But] I made sure that everyone was happy, one group one night, another the second. I tried to be fair and it worked well seven days a week.”

Moise’s Apples is Richard Burnett’s monthly Xtra.ca column on the history of Gay Montreal. Burnett is also Editor-at-Large of Montreal’s Hour magazine where he writes his national queer-issues column Three Dollar Bill.

Read more of Richard Burnett’s work on Xtra.ca.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra