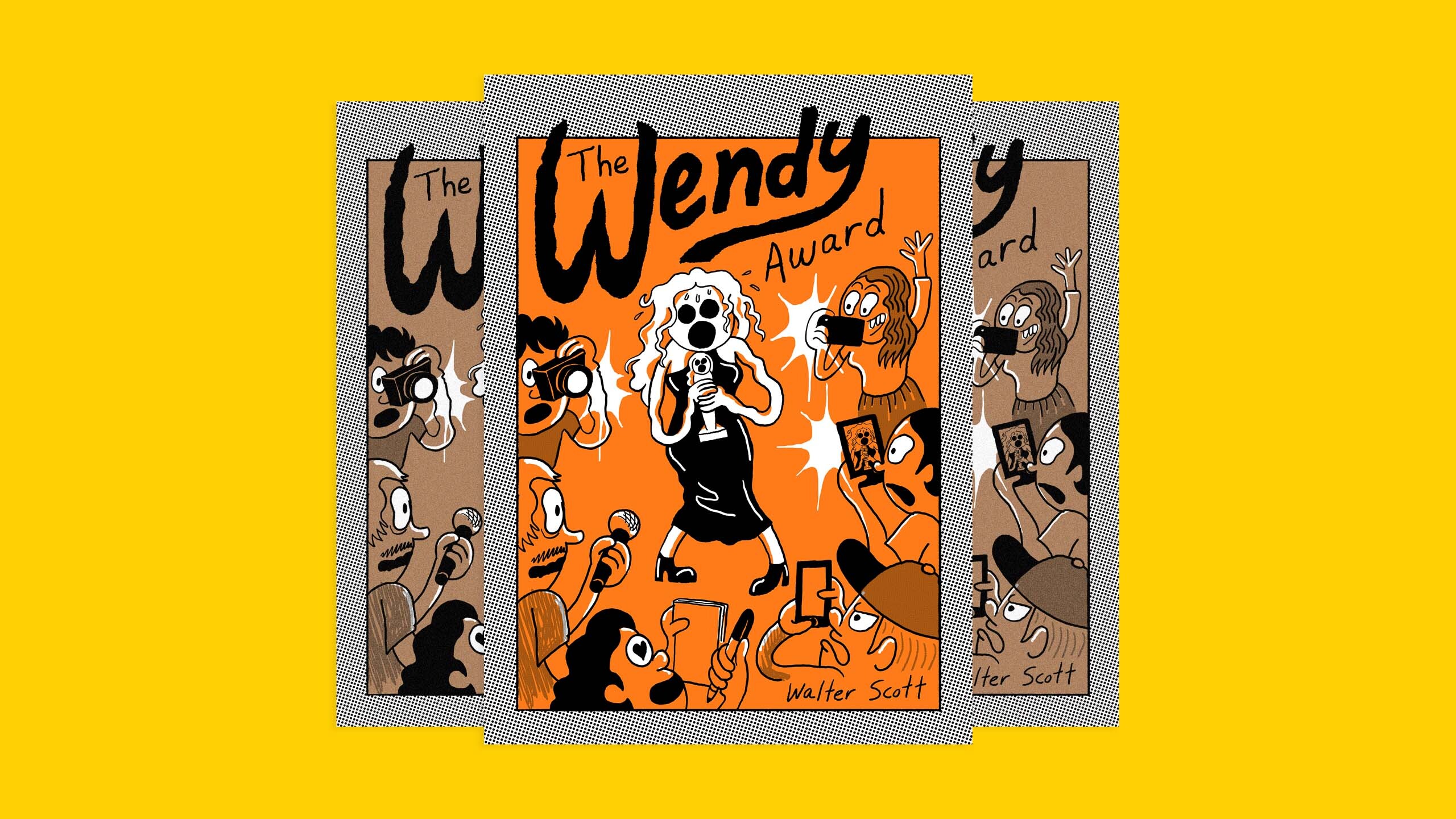

“Aesthetic choices put lives on new courses” is a motif that recurs throughout Walter Scott’s The Wendy Award, the fourth book in his celebrated Wendy comics series. Four years after the last installment, we find Wendy—a Montreal artist and perpetual mess— contending with the fallout of having created a well-known metafictional artwork called Wanda, and struggling with the pressure of being nominated for a prestigious national art prize (sponsored by “Foodhut”). This plays off of Scott’s own trajectory: readers often have a hard time distinguishing between him and Wendy, his alter ego; in 2021, he was nominated for the Sobey Art Award. Wendy’s Wanda ultimately led to a breakup with her boyfriend, Xav, whom we met in the last book, Wendy, Master of Art, and has resulted in various strangers asking her personal questions and making bold assumptions about who she is, based on her art. Wendy herself is attempting to emerge from the alienation of the early pandemic period: trying to reconnect with old friends, with little success; addressing her alcoholism for the first time; and questioning her own art practice. Maybe she’s just getting older, maybe the isolation of the last few years has reshaped her psyche, maybe it’s the pressure of getting close to corporate-sponsored artistic success, but Wendy is a changed woman in this new book. Having long teetered on its edge, she is stepping fully into the existential abyss, and it might be a good thing. Scott’s signature humour lends levity to all this self-scrutiny. As always, he’s able to switch seamlessly between gently poking fun at the worst tendencies of millennial queers and artists, and skewering arts and funding institutions with hilarious and satisfying precision.

I chatted with Scott over Zoom on a hot day in June—he was in a reflective mood, providing deeper insights about Wendy and her longtime friends Winona, and Screamo, the main Wendy trio, almost as if we were gossiping about people we knew. This familiar quality is one of the joys of Scott’s work: each character is so fully formed in these pages, even those who have two-page cameos, that after each book ends, we can imagine them continuing to live their lives just outside of the frame.

I’ve been following Wendy since you published the first Wendy zine in 2011, so it’s exciting to get to talk to you about the series over a decade in. In terms of your writing process, do you tend to conceive of each book as a project with a full narrative arc, or do you make Wendy comics regularly until a book starts to emerge?

For each book, I think of an overarching theme and a setting that I want to work with. Usually, a book will start because I’ll think of something really funny that makes me laugh. Like for Wendy’s Revenge, I had this idea of someone putting a really terrible outfit on her that she has to wear to an opening, and she feels really unconfident and she looks crazy. I ended up basing a whole book around that one little vignette. It’s one part of a larger process that I have. Wendy, Master of Art was easy to write because I had graduated art school, and low-key, my professors knew that I’d end up writing about my experience, and that’s probably why they didn’t give me any good criticism. Once I graduated, I was like, “Well great, now time to transcribe everything that just happened.” For this new book, the theme was about art work and how it changes your life, based on something I’d just experienced. I build a lattice or a framework around this one general idea, and I pepper it with funny scenes. Ultimately, if I’m not making myself laugh, I’m not interested in the project and I know that it’s not going to be interesting to other people.

Much of the comedy in the Wendy comics stems from her neuroses and tendency toward dramatic self-sabotage. In The Wendy Award, she gets short-listed for a prestigious, corporate-sponsored national art award, which is what she imagined success would look like in previous books. But of course, when the nomination comes , she ends up spiralling. What made you write Wendy into this space of ultimate self-reckoning?

Well, the last book had a very happy ending, or as happy an ending as was possible for Wendy. In this book, I was curious to see what Wendy would do after her life completely falls apart—like what happens after the happy ending? In this case, it’s a complete obliteration of everything she ever cared about. I wanted to put a character through the wringer and write them into survival mode. I guess the pandemic fucked with everybody, including me, and I just wanted to bring the readers on a journey of someone going from absolutely nothing back to a semblance of a person again. I saw myself and other people I know be completely turned inside out by the pandemic.

I imagine you’ve been dogged by readers conflating you with Wendy: your author self-portrait includes a laptop screen displaying the question: Is Wendy you? This the first time you bring these questions into the text itself, however. You have Wendy becoming famous as the author of a work of autofiction called Wanda, which muddies the line between you and Wendy even further. Did you have any fears about blurring the boundaries between you and your alter ego?

Everything that I’ve written has come from my own life experience in one way or another. For this book, I thought, “Why fight it? I might as well just make her a comic writer in her own way.” In a certain way, it’s not that deep. On the other hand, I wanted to highlight how this art she’s made has made her life more fucked up than it needs to be. The people around her are affected by what she wrote and it changes her relationships to everyone around her.

There’s this precarious balance that you strike in all the Wendy books between chaotic hilarity, and deep existential melancholia, which I think is what a lot of people enjoy about the series. However, in this book, the tone tipped even further into existential malaise. Did the pandemic influence this tonal shift? How is Wendy a changed woman in this book, compared to the last one, which you wrote before COVID-19 and published in 2020?

Do you find that Wendy’s angrier in this one? She just seems to reach the point of really not giving a shit anymore, which is exciting, because she’s always been such a neurotic and anxious character. She no longer cares about the things, the opinions, the institutions, the accolades that she used to be so hyperconscious of.

Well, I guess I feel like that. For some context, there was a Comics Journal review of Wendy, Master of Art that criticized it for being too polite and too woke, etc. On the one hand, this kind of review isn’t that interesting to me, but on the other hand, I found it fascinating that Wendy, Master of Art was seen that way by a certain audience. And any review is good information for me: like, if that book was coming off as too easy, too sitcom-y, then maybe I could stand to be a little bit ruder, a little more honest. For this book, I thought, “Well maybe I won’t put on the kid gloves this time.” In some ways, I do feel like I was trying to make everyone happy in Wendy, Master of Art. When I go back and read it now, I can see that. After the last couple of years, I don’t want to do that anymore. I can’t afford to do that if I’m going to write anything interesting. I don’t think Wendy can afford to lie anymore, to anybody. That’s why you see her grappling with her alcoholism in this book: she tries taking medication for it. She also breaks the fourth wall in this book: there’s a scene where she turns to the audience and says, “Just don’t look at me right now.” And that’s how I know that the series needs to end for a little while. We need to let Wendy have her space to just be a person.

Throughout the book, elder millennials like Wendy and Winona are thrust into mentorship roles by younger artists and writers. There are some hilarious scenes in which both Wendy and Winona try to keep up with Gen Zs, and neither of them is quite able to figure out how to engage without feeling a little alienated. Winona’s storyline is especially compelling: Zima, a younger mixed-race Indigenous artist, puts Winona on a pedestal, making her into an Indigenous auntie figure, without Winona wanting that. The relationship becomes difficult, but Winona can’t seem to get herself out of it. Why is it so hard for her to extricate herself from this dynamic?

Winona is always trying to do what everyone wants her to do, which is a pressure I’ve felt as an Indigenous artist for a long time. She moves to Berlin at the end of the book, and she says, “Fuck North America.” As an Indigenous artist, that’s not something that’s expected of you. You’re supposed to toe the line, you’re supposed to talk about your identity, you’re supposed to stick around. Winona just says, “Fuck it.” She’s had to deal with Wendy her whole adult life, on top of all this pressure. Not only is she trying to please her Indigenous mother, not only is she trying to figure out how to be a mentor to Zima, but she’s also got this complicated white woman as her best friend. All of that pressure, if I’m speaking for Winona, which I guess I’m allowed to because I invented her, leads her to finally give up on trying to be the Indigenous artist that everyone wants her to be.

Winona and Wendy both reach a point of no return in this book; each of them comes to this point separately, rather than together, as they might have done in the past. They are increasingly distanced from each other throughout the narrative.

Well, yeah, Winona has her own scorched earth, black-pill arc, as Wendy does. All of these systems that we feel are going to bring us some kind of empowerment, they’re all the same system, and Winona has lost faith, as Wendy has. I think of this book as a tragedy. Nobody comes together at the end; everything falls apart. But it’s a bittersweet tragedy, because everyone learns something about themselves. Relationships end, you know? I don’t know if Wendy and Winona are friends anymore, honestly. They tried! I think that the whole book series has never been about Wendy really trying to become a famous artist; it’s never been about her trying to find her dream boyfriend; it’s always really been this love story between her and Winona. And the end of this cycle of the series is seeing how she realizes that the biggest thing she ever got out of life throughout these years is her love affair with this one person, Winona. She learned how to love somebody, through this friendship. She learned something from it; now it has ended and it’s time to move on.

Yes, this book made it apparent to me that Wendy and Winona’s friendship is the true heart of all the Wendy books. In all the other installations, they have conflict but always reconcile. I’m glad you call it a love story because it really does feel that way. There is a sadness in this book, that the two of them can’t continue to love each other, at least not at this juncture.

It’s not that they don’t love each other anymore; it’s that Wendy finally realizes that she needs to let Winona go. She can’t continue to depend on this Indigenous person anymore to always save her. Wendy can’t depend on art to save her either; she can’t depend on the art world. She says thank you at the end, but I purposefully left it ambiguous: is she saying thank you to Winona, is she saying thank you to the art world, is she saying thank you to the viewer?

Winona’s relationship to Wendy wasn’t the only one she had to reckon with in this book.

It was important for me to highlight the dynamic between Winona, her mother and Zima. The interpersonal friction Winona deals with when the three of them spend time together doesn’t just stem from Indigenous issues, it’s also about generational issues. Different generations deal with things differently. It just so happens that there’s an Indigenous lens on the way that Winona feels the schism between her mother and Zima. At the same time, it is an Indigenous thing: Winona feels that because all three of them are Indigenous, they should all be on the same page. But that’s not how it works. There’s no one way to do things, or to think about the world, just because you’re all Indigenous. I think that non-Indigenous people think that’s what it’s like, that Indigenous people across generations are all tied together and all in agreement all the time, but it’s like, “No, honey, we all have infighting and issues with each other.” The way that my mother feels about something isn’t the same way that someone Zima’s age is going to feel about it. I wanted to highlight the disillusionment that Winona feels when she witnesses these generational differences, these gaps in understanding that can make being Indigenous even more difficult than it already is.

There’s something both rich and fraught about those scenes. Your characters never end up doing what is expected of them, an unpredictability that is really engaging.

Let’s talk about Wendy’s other longtime friend Screamo for a second. He’s still the chaotic Grindr gay we know and love, still partying and working at the grocery store, still averse to emotional entanglement, but he’s also starting to realize that he might have a new calling: fixing things. He’s especially talented at plumbing, which various characters start to take note of. In a way, being a plumber is basically the antithesis of being an artist: it’s useful, it’s unpretentious, its value is immediately clear. How did you conceive of Screamo’s storyline in this book, running as it does alongside and also somewhat counter to Wendy’s?

Screamo has simple needs, though I’m not sure he quite knows what they are. He has a lot of trauma—like, he can’t orgasm ever. When has Screamo ever come in the series? He doesn’t, because he has sexual trauma. I sound like J.K. Rowling right now: It takes Dobbie over an hour to come! Generally, Screamo has always represented the proletariat to me in the series. That sounds pretentious, but I think that Wendy’s art life distances her from Screamo, whose life is very much Not That. His roommate is an Indigenous sex worker and his boyfriend is this broke guy on E.I. Unlike some of the characters in the Wendyverse, none of the characters in the Screamoverse have it easy. It’s based on the queers I know in Montreal who are trying to keep their eye on the bag, pay their rent, you know. It’s so outside of Wendy’s life. It’s so outside of an art context. Screamo is there to highlight the broke queer part of the world.

There’s a certain point where Screamo just straight up thinks to himself that, “Oh, Wendy’s an art snob now.” That’s the last time they communicate. That’s another part of this book that’s a tragedy: Screamo and Wendy aren’t friends anymore. You just lose contact with people sometimes. Him being a plumber is simply about him doing something that isn’t art. I’m interested in this idea that Screamo is otherwise kind of useless, but he is actually very useful in this one way. That’s so outside of Wendy’s art context. And you also end up seeing that Screamo is kind of a good person, in fact. There’s the schizophrenic man whom he works with at the grocery store, and Screamo looks out for him. Screamo is a low-key Marxist. He doesn’t do this out of benevolence, he does it because he’s a broke queer and can see the reality of labour. He’s not judgmental of mental illness, of people who are just trying to keep their jobs. This differentiates him from Wendy. I kind of sneak this stuff through the back door, because people are expecting this story about some psycho-gay who just wants to fuck and do drugs, but actually through his lifestyle he’s developed his own value system.

In a way, Screamo’s the only character in this book who’s moving toward emotional intimacy by the end, toward something like a happy ending.

I think he’s the kind of person who should have a happy ending. He struggles to feel love and let it in, but he does enact love to the people around him.

I read in a recent interview you did with CBC’s Q that this might be the end of the Wendy books, at least for a long while. How did this sense of an ending come about for you?

I do feel burned out. Writing comics is really difficult, and I found myself drawing page after page after page, to the extent that it started to feel like rolling a rock up a hill. There are other kinds of art that I want to make. I want to work in TV, I want to write scripts, I want to make films, I want to make paintings and I can’t afford to not do those things right now. I want to make space for that. But also I think that Wendy’s story is done for now. The more interesting thing is to just revisit her maybe ten years from now, when I’m … Jesus, I’ll be 48. Wendy has been aging throughout the series, unlike a lot of serialized comics characters. That means the audience ages with her too. In ten years, the audience will be at different points in their lives, I’ll be at a different point in my life. There’s something juicy about waiting, about knowing that later on, we’ll get to revisit her and ourselves. Maybe she’ll be a tired art professor by then. Who knows, maybe she’ll be a trophy wife. Wendy needs to live her life for a little while, outside of the spotlight.

Are there any new projects that you’re working on that you’d like to tell people about?

I have a science fiction puppet short film that me and my colleague are submitting to festivals now, called Organza’s Revenge. It’s kind of like Wendy in space, but a whole different character. Organza is an artist with a chronic pain condition whose naturopath tells them that in order to cure it, they need to go across the galaxy and find their ex-lover and kill them. On their way to doing that, they come across a curator, and another artist, and a psychic, and it’s this space adventure where they learn something about the value of vulnerability versus revenge. There’s something very Sapphic, very lesbian about it. It’s a love story as well.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra