Melissa D'Agostino. Credit: N Maxwell Lander

Aynsley Moorhouse. Credit: N Maxwell Lander

Heather Hermant. Credit: N Maxwell Lander

Evan Vipond

Some children dress Barbie dolls in pink minis, some dress them in Sharpie ink, and some might just undress them and hide them at the bottom of a drawer. But whatever the approach, playing dress-up rehearses the connection between gender norms and our outward appearances. In Evan Vipond’s Gender Me, the trans-identified artist allows the audience member to dress him up in various pieces of clothing and body-shaping equipment while discussing what those objects might mean or say on different people.

“How do we use clothing on ourselves to create our own identities and use clothing as signifier of our gender?” Vipond asks. “But also, how does clothing become a signifier for others, and how can others interpret that and impose their own meaning?”

While Vipond takes the risky move of opening up his body for decoration and signification, the dresser then has to step up and acknowledge his or her participation in an inherited and gendered semiotics.

“I’m trying to draw on childhoods, playing dress-up with your friends or yourself, and touching lighter or funny stories,” Vipond says, “but at the same time challenging the articles through how I relate to that clothing, asking them questions about how they relate to it, to the code that is inside clothing and gender.”

***

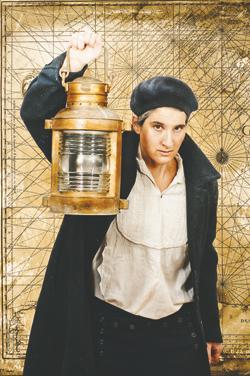

Melissa D’Agostino

Maybe it’s that breakup talk you really botched. Or maybe there’s someone you know you’ll never, ever come out to. Whatever that unattainable conversation is, Melissa D’Agostino wants to (re)visit it with you. In all the things we should have said that we never said, participants submit details so D’Agostino can assume the role of the person her one-to-one partner wants to say something to, and a risky conversation is played out in a safe and confidential setting.

“My experience is that people are very willing and interested in opening up when it’s under the banner of art,” D’Agostino says. “There’s no consequence, no feeling weird about it because you’ll have to see or talk to me again. There’s something quite freeing about that.”

***

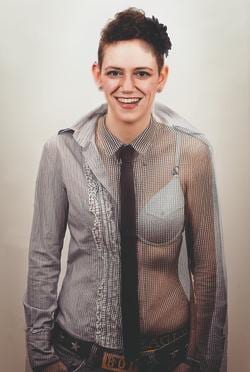

Aynsley Moorhouse

It’s impossible to truly know what it feels like to live with any mental or physical condition without actually experiencing it. Aynsley Moorhouse hopes to provide her audience a chance to better understand dementia in her piece Walk with Me.

The audience member is guided through the Village by a sound recording that imitates the experience a person with dementia might have. The recording can also be downloaded from the Buddies website.

“The technology is a convenient way to get a really intense intimacy,” says Moorhouse, who has a close family member living with dementia. “The recording can be interpreted as your own thoughts, and it can be a bit disorienting.”

In blurring perception and reality, and sensory location and identity, Moorhouse wants to challenge misconceptions about the condition, mental health and the elderly. “There’s a lot of anxiety around dementia in terms of people’s fears of developing it themselves, and dealing with people with dementia,” she says.

Because of its medium, Moorhouse’s piece is the most widely accessible of all the One-to-One works. She hopes that as many people as possible will take part. “The listener’s thoughts, memories and reactions complete the piece, so the listener sort of becomes the performer and the spectator at the same time,” she explains. “It’s a fun play on one-to-one, but it’s kind of just one.”

***

Heather Hermant

“I see it as performance and archival research,” says Heather Hermant of her two-way historical reenactment, “Aujourdhuy 15e septembre 1738.”

“I’m trying to bridge discourses in a lot of ways. Unspoken things and embodied experiences are legitimate ways of knowing.”

Her piece tackles the historical figure of Esther Brandeau, a Jewish female immigrant who came to Quebec by passing as a Christian man and who was later outed on both counts and deported. Hermant admits to being “obsessed” with Brandeau but expects that she will never fully understand her: “Every time I [perform], I have another question about the story.”

Hermant is enthusiastic about creating a one-to-one performance. “There’s this unusual intimacy between strangers by virtue of them being the only audience member,” she says. “There’s a degree of reciprocity that’s not as palpable before a bigger audience. You’re really in an exchange.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra