Vancouver theatregoers recently had a rare chance to see an Israeli troupe perform here, when American playwright Dan Clancy’s The Timekeepers took the stage at the annual Chutzpah Festival, Feb 25-26.

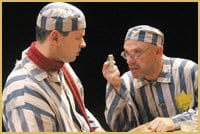

The Timekeepers tells the story of three prisoners in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp during World War II: Benjamin, a conservative Jewish watchmaker; Hans, a young, homosexual Christian who works in the same small room with him; and a criminal prisoner with the elevated status of guard.

It is a small, intimate story focusing on the distrust, conflict, camaraderie and eventual love of the two main characters, a Jew and a queer, a Yellow Star and a Pink Triangle.

Though the play doesn’t really say anything new about the Holocaust itself, it is at times a powerful and thought provoking piece about the unlikely friendships that form in the face of horror.

Its short Chutzpah run marked the first time The Timekeepers has been staged at a strictly Jewish arts festival; until now it has run at Fringe Festivals around the world, including Vancouver’s 2007’s Fringe Festival. It was also featured in Ottawa’s Pride Week last year.

Since its debut in 2002 in Tel Aviv, The Timekeepers cast and crew have taken the show to London, Dublin, Edmonton and Victoria and now plan to take it to Germany and Greece. For more than five years, every performance has featured the same cast, and it shows. It is a tight, no-frills production that is well acted and nicely paced.

The play opens with Capo the guard introducing Benjamin to his new co-worker, “the queer.” Though the chatty, earnest Hans initially gets on the nerves of the more stoic, silent Benjamin, Hans soon offers him smuggled food (he has a friend in camp who “who fucks me and gives me bread”) and uses his source to find information on the whereabouts of Benjamin’s family.

Perhaps due to the length of the play (it is just over an hour) the evolution of Benjamin and Hans’ relationship from hatred and distrust to acceptance moves way too fast. It would have made more sense to develop the relationship at a slower pace.

Still, the performance I attended was well received. The audience was overwhelmingly Jewish; I didn’t see many gay people at the Norman Rothstein Theatre.

Director Lee Gilat remembers an audience in London that was much more mixed: “I was watching the audience instead of the show. Half of the audience was full of gay, young, chic people and the other half was elderly, Jewish couples and I said to myself, ‘It’s like a reflection of what is happening in the show!’ That was a very strong moment for me.”

Gilat, a 33-year-old lesbian and Tel Aviv native, started her theatre group Ocean of Sugar as a collective in 1999. They have since produced seven plays, and while they have also staged an “AIDS drama” in the past, they are not exclusively interested in gay themes.

“We are interested in good, strong drama,” Gilat tells me over coffee on Robson St.

The reviews for The Timekeepers have generally been very positive, she notes.

“I am amazed how well it goes down, with the gay issue. But because it is funny sometimes older audiences feel we are not respecting the Holocaust,” Gilat explains.

Still, she defends her use of humour. “In the most distressful situations, people find humour that they would [not] dare use when they are in normal situations.”

I too was struck by the amount of humour in the play, but in some respects it rings false and lessens the impact a more subtle performance may have had. Roy Horowitz does an admirable job as Hans, but I couldn’t help feel at times like I was watching a queer version of Hogan’s Heroes: a little too much cheerfulness and witty one-liners.

Kobi Livne, as the criminal prisoner who guards Benjamin and Hans, plays a small but vital role in the play. He is the oppressed in charge of oppressing others treated as even lowlier than himself. The guard taunts them, belittles them and pits them against each other, unaware his circumstance is not much better.

He even goes so far as sexually assaulting Hans, in a scene that obviously made many audience members uncomfortable.

Gilat recalls a conversation she once had with a gay Arab friend of hers, who was a victim of his own upbringing and inherited values. “If I was not gay myself, I would hate gay people,” he told her.

“Any group that is questioning the order, the rules that are a form of control are putting a mirror [to society and saying], ‘We have come to a different conclusion.’ To the people who rule us, that is a very threatening notion,” Gilat theorizes.

In our discussion of oppressors and the oppressed, I am struck by the irony that one of the actors (who is gay) refused to be interviewed for this story.

Does this say something about the social atmosphere in Israel? That a gay man would not discuss his sexuality with regard to a play that tries to show our similarities with other oppressed peoples?

“The climate in Israel is not very different from Canada,” Gilat tells me. “It’s progressive with all the issues of gay rights.”

The actor’s decision not to talk was “completely personal,” she says.

I point out that although Tel Aviv — modern, urban and liberal — has hosted Pride parades and celebrations for many years now, Jerusalem only held its first gay parade last year. And there were problems. It was quite small, beset with protests and eventually the police shut it down.

Gilat smiles and jokes that her friends in Tel Aviv say the only thing that got the three religions — Jewish, Muslim and Christian — talking to each other was figuring out how to NOT have the parade in Jerusalem.

But the parade’s opponents also brought together supportive straight people, gays, Arabs, Jews, and others who wholeheartedly supported it, she points out. This coalition of activists shows that Israel wants to be a pluralist, liberal society, Gilat believes.

It is fitting that what eventually brings Benjamin and Hans together is music, a beautiful respite in the throes of all the misery they share. It does not matter that one loves Verdi, the other Puccini, and that their singing is amateur. Their sharing of the notes is what finally cements their relationship.

The play, which ends on an uncertain note for the prisoners, nevertheless ends with hope: singing in a frail and sad voice, Benjamin says, “I want to hear more Puccini” and gently sings an aria as the stage fades to black.

I ask Gilat why this play resonates with disparate audiences all over the world.

“I think it’s very human… and funny,” she says. “And dealing with such an immense part of history and a horrifying part of history, makes it the unique blend that it is.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra