This is a story about a lesbian film, a movie critic and a city that no longer exists.

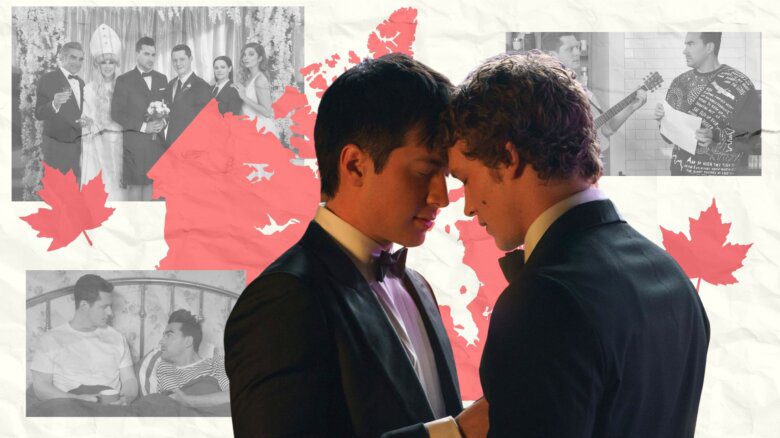

Thirty years ago, on May 5, 1995, director Patricia Rozema’s lesbian romance When Night Is Falling arrived in cinemas. I was working as a movie reviewer at NOW Magazine, which was one of Toronto’s popular arts weeklies at the time. I was also, at the age of 31, a baby dyke, having come out a few years earlier.

The thought of a full-on, big-screen lesbian romance was more than exciting to me, and the buzz had been building for Rozema’s film. It had played at the Berlin International Film Festival a few months earlier to mixed reviews, but lesbian filmgoers didn’t care so much about those. Here was a film made by a lesbian director for us, about us.

I vividly remembered the film’s opening lyrical image of a nude woman floating underwater. Stunning. But the rest of the film … is mostly a blur. It was 30 years ago after all. I remember feeling conflicted. The story didn’t work, but the intimate scenes between the stars Pascale Bussières and Rachael Crawford did. They worked really well.

With When Night Is Falling’s 30th anniversary approaching, I decided to rewatch the film. I hadn’t seen it since that press screening so long ago and I wanted to revisit a film that celebrated lesbian love in a time when that was oh-so rare. Would I still feel conflicted? Disappointed? Enchanted? Would the film have aged well or would it feel like a queer artifact?

What I discovered was a lesbian fairy tale; a flawed movie, yes, but one that moved me more than I expected.

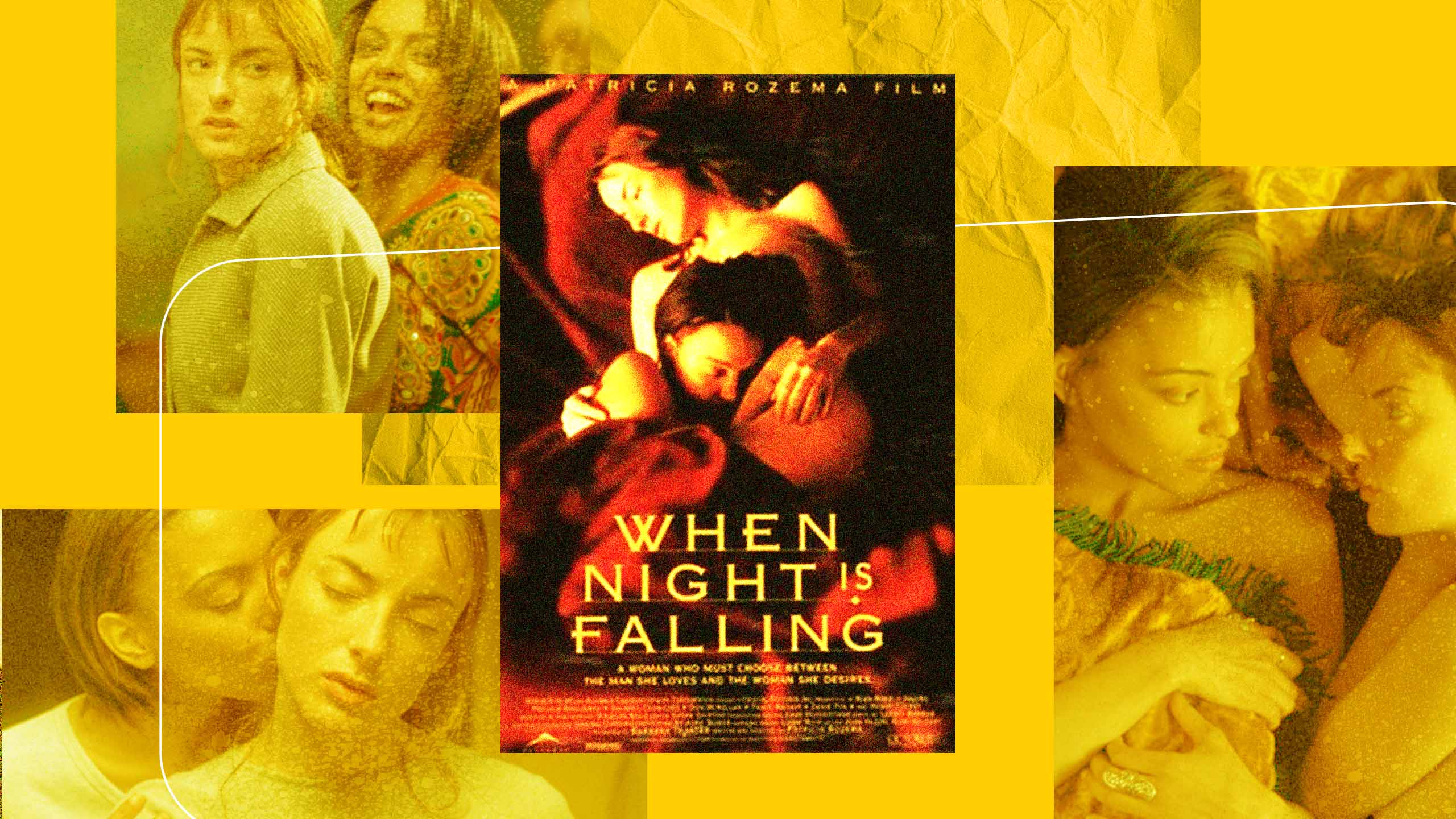

The story revolves around meek mythology professor Camille Baker (Bussières) who teaches at a Christian college in Toronto (the film was primarily shot in and around the University of Toronto’s downtown campus). She’s engaged to theology professor Martin (Henry Czerny), but we can sense almost immediately that Camille harbours doubts about the relationship.

Camille is rocked to the core when her beloved dog dies, and while crying at a laundromat, she meets and is comforted by Petra (Crawford), who takes a shine to her. When their laundry is mixed up, Camille learns that Petra is a performer in a travelling circus, and in a spontaneous moment, sensing the attraction between them, Camille heads to a lakefront warehouse in Toronto’s Liberty Village neighbourhood where Petra’s arty circus is camped. Petra, who is unabashedly out and proud, woos the conflicted Camille, who eventually overcomes her internalized homophobia and falls into Petra’s arms.

Smug boyfriend Martin discovers the affair and, in a moment that’s both menacing and restrained, demands she end it, causing Camille to attempt to end her life only to be saved by Petra. Improbable. Hokey. And don’t ask about the dead dog, that part is just confusing.

There is something both incredibly naive and mature about the movie. Camille is an enigma, a blank page waiting for someone or something to imprint upon her. This is not a conventional coming out film in which the woman is young and yearns for the person who;ll help her embrace her queer sexuality. Rozema gives us none of Camille’s backstory, no explanation for why she is so sad, why she is with Martin or why she takes the leap with Petra. Was she always a gay woman looking to break free or is Petra the shooting star that captured her heart?

It’s up to us to fill in the blanks, and I appreciate that. There doesn’t have to be a big dark secret haunting our onscreen queer characters. I could relate to that as someone who came out later in life.

Watching the film 30 years later, I also appreciate Bussières’s interior, watchful performance. You can see her desire in small, almost imperceptible movements. Crawford also shines, and, here again, her backstory is shaded. Did she run away to join the circus? Why? It doesn’t matter, all that matters is that she is a woman who has fallen head over heels in love with a woman who is nothing like her.

The bow that wraps the film like a gift is a beautifully shot sex scene between Petra and Camille that remains one of the most evocative, and hot, in lesbian cinema. This alone is a reason to see and cherish the film.

I am also struck by a Toronto that is long gone. Though the scenes set in and around U of T show a campus that remains familiar, shots of Liberty Village, with its old brick warehouses and wide-open spaces looking out over Lake Ontario, haven’t aged as well. Today, Liberty Village is a high-density development with warehouses either gone or transformed into supermarkets, restaurants and furniture emporiums. I now know what it feels like for longtime New Yorkers to marvel at old films set on their streets and contemplate what their city once was.

Looking back, I realize the mid-’90s were a glorious time for a movie-loving lesbian. We didn’t know it then … no that’s not right … we didn’t appreciate that we were living during the golden age of indie queer cinema. The action-packed, soulless studio blockbusters of the 1980s had lost their lustre. Hungry young filmmakers, backed by small independent film studios and distributors, were stepping behind the camera to make movies about ordinary people, often focusing on marginalized, young and queer characters.

By 1995, gay films featuring gay men had strutted across screens—Zero Patient, Paris Is Burning, My Own Private Idaho, The Living End and Poison—capturing queer politics, culture and sexuality. But the golden age of lesbian films was just getting underway. The release of When Night Is Falling was followed a month later with The Incredibly True Adventures of Two Girls in Love. In 1996 we submerged ourselves in The Watermelon Woman and Bound. In 1997 we fell for All Over Me, in 1998 Hight Art and the decade-ending 1999 gave us Better Than Chocolate, Chutney Popcorn and But I’m a Cheerleader.

It was a time of hope and exploration. In 1995, we were given a peek into the Sapphic cinematic explosion to come with When Night Is Falling. For that, we should be forever grateful.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra