Despite making up 24 percent of the world’s population, Muslims are vastly underrepresented in Hollywood. Out of 8,965 speaking roles in films examined by the Pillars Fund in 2021, only 1.6 percent of those characters were Muslim. What’s worse, in all of those roles only one character identified as part of the LGBTQ2S+ community. In a society that claims to be focusing on inclusivity and representation, it’s critical that we get more roles that represent the various ways that people practice (or don’t practice) Islam. That’s why seeing a film like The Syed Family Xmas Eve Game Night is so revolutionary for Muslims. The short film premiered last month at TIFF and is screening both in cinemas and online at the Chicago International Film Festival (Oct. 14 to 24).

Directed by Fawzia Mirza, and written by and starring Kausar Mohammed, the 11-minute short follows Noor (Mohammed), a queer Muslim Pakistani woman who brings her Puerto Rican girlfriend Luz (Vico Ortiz) home for the first time for her family’s annual game night. Things get a little turbulent, though, when Noor’s eldest sister (Meera Rohit Kumbhani) unexpectedly shows up, putting all of their relationships to the test. Within seconds, audiences will find themselves in love with the characters scribed by Mohammed and by the time the short is over, you’ll be wishing this was a feature film.

I spoke with Mirza and Mohammed ahead of their film’s debut as part of TIFF’s Short Cuts Programme. We discuss the inspiration for the short, the importance of differentiating between cultures in the Middle East, North African and South Asian regions and the many other types of Muslim stories yet to be told.

I have to say, it was absolutely inspiring seeing queer Muslim people from the Middle East/North African and South Asian regions represented on screen. What inspired this story?

Kausar Mohammed: Well, I have two [older] sisters whom I love very, very, much. I also have a partner that I love very much, my girlfriend. The first Christmas that I introduced my partner to my middle sister, everything was great. But being there and having the anxiety of bringing someone you love to meet someone you look up to so much, it had my mind thinking up all these things that could go wrong. A Taboo game going wrong was one of them, so was a chai battle. That’s how I came up with the idea for this short.

And as I was writing it, in my mind the person I really dreamed to direct it was Fawzia. I know her—we’ve worked together before—and having someone who is also of queer, Muslim, Pakistani identity was so amazing. It honestly took it to another level.

Fawzia, when you read the script did you immediately know how you wanted to direct it?

Fawzia Mirza: I didn’t know immediately how I wanted to, but I did immediately know I wanted to direct it. Directing is a newer endeavour for me, and as someone who comes from creation in the indie space, it’s a place I’m excited to embrace. When Kausar asked me and sent me the script, as she said, it was exciting to be able to work on this through a shared lens. That’s never happened for me before, and still Kausar is the only person I’ve really had that experience with. Coming from that shared perspective and spectrum of identities was and is a dream, and as we go into the world premiere and beyond that will continue to be something that is central to why this matters so much.

I love these characters and fell in love with them so quickly. If you could expand the story into a full feature, what would that be about? Have you thought about it?

Mohammed: That’s the plan!

Mirza: [Your love of these characters] is a true testament to the personal space that Kausar comes from, bringing these characters to the page. In terms of casting, it came to authentically casting these really vibrant personalities and members of our community in these roles. And when I say authentically, I mean not just by virtue of their South Asian-ness, but by virtue of their authentic personalities, who they are and what they bring. As far as the feature goes, it definitely is something we’re talking about and have some interest in.

I feel like I need to clarify something, because earlier I said I was happy about these Middle Eastern stories coming on screen, but this is South Asian. I’m re-connecting to my roots and learning this all from scratch myself, so do you consider it a faux pas when people say this is a Middle Eastern story and not a South Asian story?

Mohammed: Everything we’re told about where the Middle East and South Asia are is told through a lens of colonization. In that [respect], I do like to call it a South Asian film. On a larger level, I’m curious as to how the way we categorize ourselves plays into the way people in the diaspora are given opportunities. It’s something I’m still figuring out, but I think the more we dig then the more there is to find out.

Mirza: I think the thing we can do is always be specific, and that specificity brings out the universal aspects. In this case, the specificity of having a Pakistani writer and director, we’re bringing that experience, though not all of our actors are necessarily Pakistani. That kind of specificity allows us to really dig in and tell this story, and that becomes universal across experiences.

I see the similarities in the cultures, and I think that makes it harder and easier. In Palestinian culture, tea is also very critical so I immediately understood the importance of the girlfriend making tea. It’s interesting how different Pakistani tea culture is from Palestinian culture, but also interesting how easy it is to mix it up.

Mohammed: You hit it on the nail! There’s that unspoken testament to doing tea. You gotta do it and you gotta do it right. I think a lot of other cultures can also resonate with that.

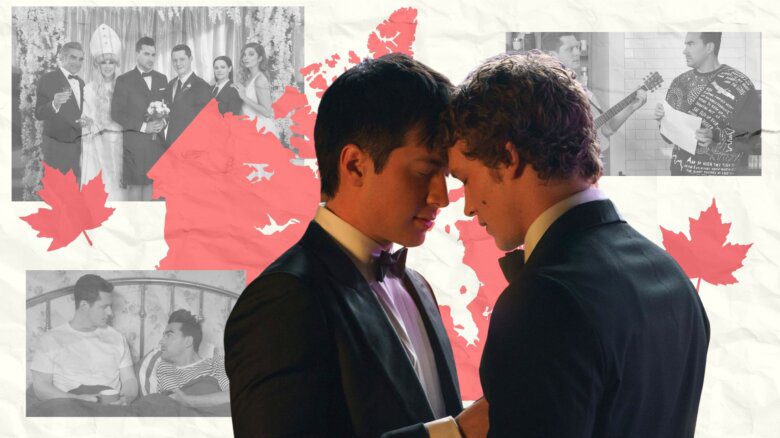

Credit: Courtesy of syedfamilymovie.com

The inclusion of non-binary and gender nonconforming characters is so critical to teaching people about us, and I love that you cast Vico as the girlfriend. Was that an intentional choice or did they just shine during auditions?

Mirza: Vico is an exceptional talent, and a friend. [In the past], we did a reading of a feature length screenplay where I cast Kausar and Vico to play love interests, in a queer Agatha Christie murder remake. When Kausar and I started talking about casting, we both just went, “Yeah, I think Vico [is perfect for this].”

Mohammed: Vico brings such lovability and humour to the character, and it being a short film, you only have 10 minutes to make sure that girlfriend is likable. It was a no-brainer to bring Vico in.

Mirza: To touch on your other point as well, the intentionality of casting, that was something that was very important to us. There’s Vico, and there’s also D’Lo [Srijaerajah], who’s a trans man. These are friends from our community, and part of what makes this film so special is that it’s informed by the people we see and spend time with in our daily lives, and casting them in all the different ways we see each other.

How does it feel to tell queer Muslim stories at major film festivals like TIFF and Chicago?

Mohammed: One of the things that sort of drives the project is the desire to normalize our stories, and to tell them on a big screen because they’re worthy of that. I’m thinking of a quote, “Only monsters don’t see themselves reflected in mirrors.” Then I think about the comparison of historically marginalized identities not seeing themselves in this mirror that is media. So, how can we bring our reflection back? The fact that we can bring that back at a place like TIFF is amazing. We are super grateful for this opportunity and thankful to have a collaborator like Fawzia, who I attribute so much of this elevation to.

“It’s so important for us to be at the centre of the story. Truly, our mission is to have queer, Muslim, POC protagonists.”

Mirza: It is definitely super exciting, and it’s our first time at TIFF. It’s my first time there, and they’ve been so good to me over the last year and a half. I went through their feature film writer studio and filmmaker lab with a project, and I feel really supported. It’s wild when you think of the kinds of films that you think are supposed to get into a festival of this kind, and being seen for such a joyous, made with love, type of film. For TIFF to program the film, to us, feels like not just an important step for us and our careers but for our lives, and a step towards stopping the violence perpetrated towards our communities.

Do either of you feel any sort of pressure when it comes to representing South Asian or Muslim people in film?

Mohammed: I think I used to because I was feeling—and I think this happens in communities that don’t get screen time—this feeling of representation anxiety, where there’s only one thing that gets the shot and that one thing better get it right, or we’re all screwed. I alleviate that pressure by the idea of everyone needing to create their own stories. My story can speak to me, but how can we get as many stories out there as possible?

Mirza: I think coming from the kinds of backgrounds we come from, we all know that feeling of never being able to please the parents, or the aunties or uncles, and everyone’s always gossiping. The truth is, people will always have those opinions regardless of what you do. This often happens when we’re mistakenly raised to believe we should be living our lives to please other people. I know I found true freedom in releasing all of that, because they’re always going to say what they’re gonna say.

Even with this film, a Muslim Christmas rom-com, that’s just about the feel goods. Even this has received a lot of hate because there’s Muslims that think that gay people shouldn’t represent the Muslim community, or Muslims preferring to be represented as terrorists than have a Christmas tree or be seen as queer. It continues to remind us of Kauser’s point, which is why we need more stories. It’s scary out there and people need to continue to see themselves, and also to see a breadth of experiences beyond their own.

Mohammed: And on a very real level, too, the homophobia in the Muslim community is very real. All the more reason why we need all the different types of things.

Where do you see representation for Muslims going in the next few years, and what do you think we need to do to get there?

Mohammed: We just need more. I think the Riz Ahmed study that talked about the lack of representation for Muslims in media in general is a stark reminder that we have barely started to see Muslim stories. Also, how wide is our community itself? How do we centre stories within the Muslim community that we don’t hear about? Our Black Muslim stories, our non-binary Muslim stories, our disabled Muslim stories.

I crave to see more of that, so that as a whole we can see the vastness of what Muslims are and can be. I think that can be done by the community standing behind each other, and uplifting each other nonstop, even when the experience doesn’t feel like the experience you personally identify with. As long as it’s not harmful, how can we uplift it and share it?

Mirza: It’s so important for us to be at the centre of the story. Truly, our mission is to have queer, Muslim, POC protagonists. If we were talking even six months ago, or three months ago, it’ would be a different conversation. In this moment, it’s exciting to see things like Bilal Baig’s show, Sort Of, now being picked up by HBO and the CBC, and there’s another great show being shot based off a memoir by [Amrou Al-Kadhi], a Muslim drag queen. And that’s still only two folks out of our vast Muslim empire. That is so fresh and new that we haven’t even gotten to see those stories yet. Before that, there was the one character on The Bold Type, and people would say, “Remember, you got her!” And we’d say that’s a problem, because we didn’t even get to know what country she was from in Season 1. And there was no one Muslim writing for her for three seasons of the show. There’s so much to be done, and this is just a step in the process and that’s exciting.

This story is published with support from the Ken Popert Media Fellowship program.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra