Queer characters have been represented onscreen since cinema’s early days, especially in horror films. Director James Whale, who was openly gay in the 1920s and ’30s when he was making some of his best-known films, was an early pioneer. Whale brought us iconic films like Frankenstein (1931), The Invisible Man (1933) and Bride of Frankenstein (1935). But it’s The Old Dark House (1932) that is one of the boldest of the time in terms of its queerness. The film is composed of an entire family of gay-coded characters: patriarch Roderick Femm is played by a woman (Elspeth Dudgeon), son Horace is played by gay actor Ernest Thesiger, sister Rebecca (Eva Moore) is a closeted lesbian and Saul (Brember Wills) is understood in contemporary readings to be a repressed homosexual.

In the 1930s, Hollywood introduced what was known as the Hays Code, which prohibited “any inference of sex perversion.” (The code was seriously enforced starting in 1934, so Whale already had a head start.) Harry M. Benshoff, who discusses horror and homosexuality in his book, Monsters in the Closet: Homosexuality and the Horror Film, suggests that there was an obvious thread of “filmic homosociality” during the Hays Code period; queer representation was not erased from the screen but rather hidden in plain sight. In other words, queer people existed only in subtext—and most often as villains.

To get queerness on the screen, filmmakers found creative ways to subvert the system. In horror, cinematic “monsters” became a metaphor for queerness “whose sole purpose in horror films is to subvert society before meeting their expected demise,” suggests literary critic Nathan Tipton. Death-by-design was the status quo for decades for queers in the horror genre. Even if they began the film as predators, they ended up as prey.

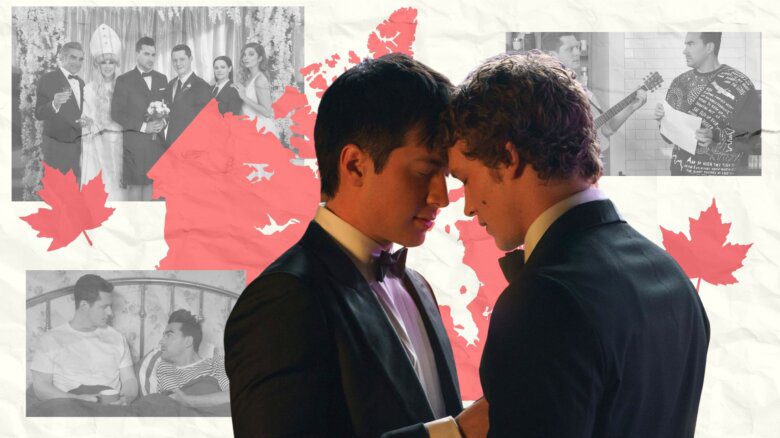

Two recent lesbian-centred horror films from Canada, The Retreat and Bloodthirsty, are part of a modern canon that rejects these patterns. Bloodthirsty is directed by Montreal’s Amelia Moses—whose feature debut, Bleed with Me, was one of Fantasia 2020’s biggest surprises, presenting the insecurities and anxieties of female friendships through a homoerotic, horror lens—and written by the mother-daughter team of Wendy Hill-Tout and Lowell, a bisexual singer/songwriter. Queer screenwriter Alyson Richards penned The Retreat, which is directed by Pat Mills. (Mills caused a buzz on the LGBTQ2S+ film circuit back in 2014 with the comedy Guidance, which he wrote, directed and starred in.)

These two films still embrace the “us versus them” mentality that makes the queer-inflected horror films of the past so fascinating——the literal and metaphorical view of queer people as animals/monsters. But these Canadian filmmakers subvert and radicalize the canon’s tropes. Queer characters may still be seen as monstrous by those who are prejudice against them, but here they are no longer the ones preying on the innocent and requiring punishment for doing so. And unlike horror films of the past, contemporary films no longer under Hays Code restraints are able to show clearly that the monsters are those who hunt the queer characters. Some recent queer stories (The World to Come, Carmilla, To the Stars) are still plagued by the “bury your gays” trope, a term coined because so many queer female characters end up dying on TV shows. But The Retreat and Bloodthirsty are about women who survive, no longer having to hide or succumb to the hunt.

The “us versus them” mentality, which defines certain characters as “others” who might contaminate “us,” is central to horror cinema; it’s that desire for moral preservation that informs even the most modern takes on horror. This is the case in The Retreat, as Renee (Tommie-Amber Pirie) and Valerie (Sarah Allen), a couple at a crossroads in their relationship, leave the big city to spend the weekend with friends at their cabin in the woods. When they arrive, however, their friends are nowhere to be found. What was supposed to be a cozy and relaxing retreat turns into something much more violent. Renee and Valerie’s out-and-proud lifestyle isn’t met with the same tolerance in the backwoods as it is in urban settings. Though they are the “others,” we watch the story unfold from their perspective—and the extremists who live in the nearby town don’t tolerate any upsetting of their moralist views.

Soon, Renee and Valerie are being followed and watched. In a reversal of cinematic tradition, the queer couple is the prey, at the mercy of their surroundings and these extremists who are waiting to pounce on their next meal. It’s easy to wonder: Are they mere victims, part of the “bury your gays” trope? But then the narrative shifts; Renee and Valerie are no longer the ones being brutalized, and they demonstrate they can take care of themselves. No more death-by-design, these characters are resilient and can hold their own against violence. It’s not a perfect film, as it sticks to past queer representations more than it should, but it manages to creatively take back lesbian horror narratives.

Even more than The Retreat, Bloodthirsty hearkens back to the classic “universal monster” films: over the course of the film, its main character, Grey (out actor Lauren Beatty) transforms into a werewolf. The portrayal of queer characters as literal monsters had started to fall out of fashion with the loosening the Hays Code in the 1950s and its subsequent demise in 1968; filmmakers no longer had to sneak queerness into their projects. Subtext became text in films like The Haunting (1963), where one of the main characters is an out lesbian and, above all, is not portrayed as a monster. Queer characters finally came out of the closet, but lesbians, in particular, were still often sexualized by the male gaze. While lesbian characters were present in the horror genre as early as the 1930s in vampire films like Dracula’s Daughter (1936) and in Hammer Films (the famed U.K. company that produced Gothic horror films from the 1950s to ’70s), we finally start to see, “openly homosexual characters become commonplace within the genre, sometimes as victims,” writes Benshoff, “but more regularly as the monsters themselves (the lesbian vampire).” The Vampire Lovers (1970) was one of many films that portrayed lesbians as rich women who seduce the young and powerless. From the male point of view, which dominated film studios, female sexuality was seen as monstrous. Author and filmmaker Andrea Weiss suggests that lesbian vampires were created “as an articulation of men’s subconscious fear of and hostility toward women’s sexuality.”

Credit: Courtesy of Voice Pictures

Also working with tropes of predator and prey, Moses has a more sympathetic take on female sexuality. Bloodthirsty draws on many influences, from the TV series Buffy the Vampire Slayer to 1992’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula. But the film’s opening scene feels like something out of Raw, a 2016 film about a young woman who craves human flesh—Bloodthirsty’s Grey, a vegetarian, is shockingly seen devouring flesh and bone.

A musician struggling to find inspiration and her voice, Grey, along with her girlfriend, Charlie (Katharine King So), accept an invitation to stay at the home of an eccentric, famous musician named Vaughn (Greg Bryk). The film, for the most part, is about art and the creative process; the collaboration with Vaughn reveals what has been holding Grey back.

“Queer monsters may be a device through which to scare, but they aren’t truly monstrous; they’re not inexplicable.”

There’s obviously something vampiric about her, and she explains to him that she has hallucinations in which she turns into an animal: long fingernails suddenly appear on her hands, and there are scenes where she pulls out her teeth. She’s ravenous, and her character feels like an ode to the monstrous femininity of Hammer films—just without the leering sexualization. A part of her identity is missing and Vaughn’s dark influence helps reveal it. But her transformation isn’t simply a hallucination, it’s reality—she is, indeed, a werewolf. Vaughn is, too. And just as in the queer community, like gravitates toward like. Vaughn explains that lycanthropes were hunted as prey for centuries, and he believes it’s time for the two of them to become the predators. He has a taste for human flesh, but Grey doesn’t want to be “a monster.” In Grey’s resilient pride and acceptance of herself, she chooses not to follow in Vaughn’s path. In Bloodthirsty, Moses shows how queer monsters may be a device through which to scare, but they aren’t truly monstrous; they’re not an inexplicable “them.”

Credit: Courtesy of Voice Pictures

What ties both The Retreat and Bloodthirsty together, as well as to the queer-coded horror films of the past, is the idea of “culling the herd.” Meant for animals, the concept can be applied to any horror film dealing with predator versus prey. Richards’ screenplay, especially, relies on the idea of deer as a metaphor for the queer community; Renee recalls her experiences of hunting as a child to “cull the problem deer.”

“Were they a problem? The deer?” Valerie says.

“Depends on who you ask,” replies Renee.

It’s a simple but poignant phrase that reminds the audience that homophobia, arbitrary as it is, remains ever-present. Homophobic extremists in The Retreat want to cull (or kill) Renee and Valerie, who they consider “inferior” human beings, just as Bloodthirsty’s Vaughn culls humans believing he could never be “out” as a werewolf. Queerness is undesirable and so it must be hidden, destroyed or weaponized in much the same way that classic horror films kept queer characters disguised or risk them being culled by the censors.

Before the Hays Code made directors devious, otherness in classic queer-inflected horror films was not depicted as monstrous; what was monstrous was how “otherness” was defined and treated. Following in this tradition, the monsters in The Retreat are those unaccepting of otherness in society. In Bloodthirsty, the character who can’t accept the otherness within himself is the problem. The role of predator and prey have shifted, along with society’s view on homosexuality and gender nonconformity. Both The Retreat and Bloodthirsty demonstrate that, above all, queer characters are no longer disposable; they can be the leads, even if they scare us.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra