Local Toronto hero Catherine Hernandez has come a long way since she first attended the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) as an usher at the Winter Garden Theatre, making $6.25 an hour trying to get people to sit in their seats so the show could start. Now, Hernandez is wearing the coveted filmmaker’s lanyard and receiving acclaim as the writer of Scarborough, the film adaptation of her award-winning debut novel of the same name. After it screened last year, the film was purchased by levelFILM, and should get a commercial release soon.

The book was a joy to discover, as it introduced the world to parts of Toronto that Drake rarely mentions. Formerly its own suburban city, Scarborough is now part of the City of Toronto, and has a local reputation as the backwater second-cousin of Toronto proper. But that stereotype seems largely a function of unfamiliarity; Scarborough isn’t well connected to other parts of Toronto, and her charms can be a mystery for anyone who doesn’t have friends or regular business there. The “undiscovered country” vibe is also, unfortunately, partly just racism—Scarborough is home to a high concentration of immigrants and refugees, many of whom are seeking access to the big city at the lowest possible price. While not a lot is fancy, residents feel very connected to their community.

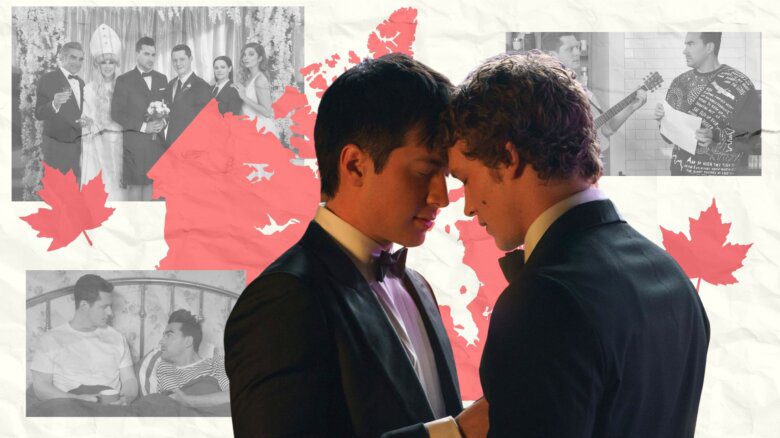

Scarborough the book earned Hernandez an impressive slate of awards, including the Trillium Book Award, as well as a spot on many best-of lists. Just this month it was nominated for the longlist of Canada Reads, the country’s battle-of-the-books competition, for the second year in a row. Her success did not come as a surprise to the Toronto theatre community, where Hernandez has been making minds expand and hearts bloom for more than a decade. In the move between stage and page, Hernandez brought all of her best theatrical instincts, an unmatched lyricism and her upright and unapologetic commitment to justice. She’s kept all these virtues as she’s moved to film. Scarborough introduces us to three households through the story of three children: Bing (Liam Diaz), a gay Filipino boy; Sylvie (Essence Fox), an Indigenous girl; and Laura (Anna Claire Beitel), whose home life is especially rough. The film was made in the community, with local actors.

Xtra spoke to Hernandez when the film opened at TIFF.

The book Scarborough has queer characters, and what I would describe as a queer sensibility. But when we see what we think of as “queer movies” at mainstream festivals, like TIFF, I think that people have an expectation of what a queer film looks like. How does Scarborough fit?

I’ve heard [writer and artist] Vivek Shraya say, about [her picture book] The Boy & the Bindi: “I really wanted to write this boy, trying on something feminine, and this mother affirming him in this act. If we don’t imagine positive things like that, it won’t ever happen.”

And overall, “queer” is more a verb to me. You “queer” something because you’re trying to imagine something better, right? It’s not only about body parts, it’s not only about orientation. I really feel queerness is just as much about imagining things and making it happen.

The story around Bing is definitely me wanting to imagine for Bing this Filipina mother, Edna (Ellie Posadas) who really loves her fat, feminine, gay son. Because it’s possible. Have I seen it? Rarely. But it’s possible. I think that’s why so many people fell in love with that relationship between Bing and Edna, because I imagined something that I think that many of us really long for. That it exists as a possibility.

As a brown, queer woman, there are a lot of things I don’t have power over. But I have absolute power in what I write. I can write whatever the fuck I want. And this is what I wrote: I wrote Bing into being. It’s just been, for me, a really empowering moment because as much as we can keep on imagining it, it will happen, you know?

My parents certainly never saw a movie where people were excited to have a queer kid. That, I think, is one of the things I love about Bing and his mom’s relationship in Scarborough—she’s not just tolerant or accepting, she fully celebrates Bing.

Yes. Yes. She celebrates Bing. It’s a little strange adapting a book to be a movie, especially your own book, but there’s a line that I was really happy that stayed in from the book, where Edna says: “You’ll never be too little, Bing, and you’ll never be too much.”

I think that scene, and that relationship, has a lot to do with the fact that Edna has a history with her brother, who had passed away, and that she knew that she was complicit. She did not affirm her brother in his identity. I think the thing she’s seeing in her son is also partly the potential of reversing those wrongs, which is another queering. Trying to re-imagine the past, to apologize forward—if you can’t apologize to the person, it feels like queer re-imagining also.

I know the novel did very well, and you had multiple offers from people interested in adapting the story to film, but you chose a small documentary team. I am so curious about why.

I was approached by a few filmmakers when the book gained some traction, yes. These filmmakers were sending me their reels, hoping I would consider letting them option the book. I’d look at their reels, and they were very polished. So slick and fancy. I thought, honestly, my community is not polished. Not fancy. We’re not a fancy bunch of people.

And I knew that the worst thing I could watch is someone who’s, you know, a fancy actor, someone who’s really well known, putting on some strange accent that they believe is Scarborough. That would make me die inside, like, my soul would sort of fly out of my body.

So, I contacted [documentary filmmakers] Shasha [Nakhai] and Rich [Williamson] and I said, “What do you think about this? What if I were to write the script myself—could you shoot it like a documentary? Is that even a possibility?” They said yes. I wrote the screenplay in two weeks, because there was a deadline coming up. And I thought, I might as well just write it. I was going to give them the specs, the script, just so they could see what I imagine. And the next thing I know, we’re shooting. Just so bizarre. So exciting, so amazing, but so bizarre.

What else is exciting and amazing right now? What doors are opening for you as a queer woman of colour, as a queer femme, as a queer writer and filmmaker, because of the film doing well at TIFF and getting a commercial release?

There are a few projects—definitely some of them queer-focused that I’m just really so excited about—that are on the horizon for television and film. But mostly, I just want to keep on telling these stories. I feel like storytelling is a really big component of our resilience as queer people. Our storytelling takes the form of burlesque and drag and dance and fashion and clowning and kids’ books—just all of it. You know, there are so many ways we tell stories, but it’s a way of documenting us being together in our understandings. The mainstream will never document our history, and certainly not the history of brown queers from the unfashionable part of the city. We have to do that for ourselves and the idea that this gets to be part of my paid work is just… It’s a dream.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra