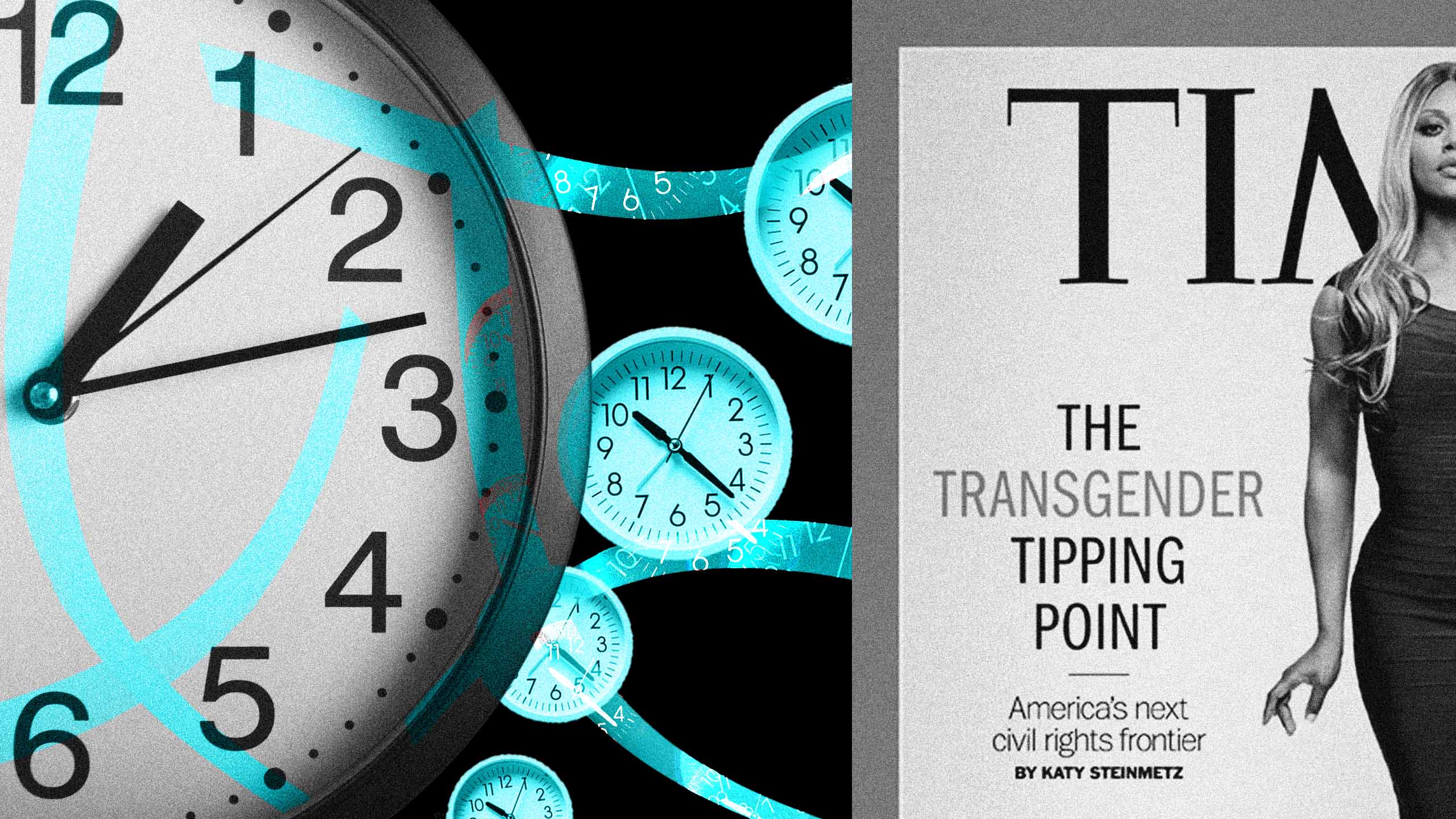

Ten years ago yesterday, TIME magazine declared a “transgender tipping point.” “Almost one year after the Supreme Court ruled that Americans were free to marry the person they loved, no matter their sex,” wrote cis journalist Katy Steinmetz, “another civil rights movement is poised to challenge long-held cultural norms and beliefs. Transgender people—those who identify with a gender other than the sex they were ‘assigned at birth,’ to use the preferred phrase among trans activists—are emerging from the margins to fight for an equal place in society.”

The idea of a “trans tipping point” became ubiquitous. Even if you never read the article itself, the cover, featuring Laverne Cox—one of the first trans actors to receive mainstream recognition, and the first trans woman ever to appear on TIME’s cover—was everywhere. “For years after, academic and media writers alike would cite that story, or the paradigm shift it detailed, in our articles, often grounding it in our ledes,” says journalist Harron Walker. “I don’t really see that happen anymore. So, that’s one thing that’s changed between then and now: we don’t really cite the Trans Tipping Point anymore.”

In fact, the idea of the “trans tipping point” has become something of a joke among trans people. Ten years later, we are subject to even more widespread hatred and legalized bigotry; if trans people have “tipped” in any direction, it’s backward. Yet things are rarely that simple. To take stock of the moment, 10 years later, I reached out to nine trans experts and asked them what has changed.

Something to build on

Even when it was first published, many trans people had complicated feelings about the TIME article. “The trans tipping point, at the time, was a moment of trepidation,” says Florence Ashley, author of the recent book Gender/Fucking. “Many of us were aware of the limits of visibility, yet we let ourselves hope that this would be for the better—at least I did.” Katherine Cross, digital sociologist and author of Log Off, remembers that “there was a fear that this meant the Eye of Sauron was upon us, that whatever safety was afforded by the shadows of public ignorance was well and truly gone now.”

“My last film, Disclosure, was inspired by the ‘trans tipping point’ cover story,” says filmmaker Sam Feder. “I was thrilled for Laverne, but it felt like a punch in the gut. This was not the tipping point the community needed. Laverne used her platform to speak about critical issues, but that was lost on most who just wanted to celebrate our visibility or get a piece of the pie.”

Trans healthcare advocate Jamison Green was interviewed for the TIME article. “I thought at the time that it was a very good summary and overview of the issues trans people face, and certainly everyone loves Laverne Cox,” he tells me. “At the same time, though, I also thought it was premature to imply that trans people had overcome—or might be on the verge of overcoming—our collective obstacles. I knew the hate ran deep.”

Being named as the newest minority to “emerge from the margins” has rarely worked out well for anyone. But it was, in its way, progress—mainstream media outlets that usually couldn’t manage to refer to trans people by their chosen names or correct pronouns were now featuring us on their covers. It was a “moment of hope,” Cross tells me, “a moment that seemed to prefigure full citizenship, and acceptance by the political mainstream, however grudging. It was, in short, something to build on.”

The baby trans boom

As Whipping Girl author Julia Serano explains it, the “tipping point” had been building for quite a while before it showed up on the cover of TIME.

“For most of my life, the trans experience was typified by isolation and invisibility. Most of us grew up not knowing any other trans people, and this sense of isolation was reinforced by how infrequently trans people and issues were covered in the media,” Serano tells me. “Gender-affirming care was also extremely difficult to access, both because there were very few providers and most adhered to strict gatekeeping.”

In the early 2000s, two things changed: First, trans people were increasingly connecting with each other on the internet and building a thriving queer subculture that transcended regional boundaries. Second, gender-affirming providers began to drop strict gatekeeping requirements and moved toward an informed-consent model, making it exponentially easier for people to transition on their own terms. The result was a boom in trans people’s numbers and social visibility.

By the early 2010s, Serano tells me, that population boom “began bubbling to the surface in the form of increased media coverage of trans people and issues. Some at the time, including TIME magazine, misinterpreted this increased trans visibility as a sign of mainstream acceptance; anti-trans activists would later misinterpret it as evidence of ‘transgender social contagion.’”

In fact, it was just trans people gaining critical mass and becoming a legible demographic within capitalism. This has happened to many marginalized populations over the years, including, notably, cis gays, who went from untouchable cultural Others to sitcom fodder over the course of the 1990s. Becoming a known slice of the market meant co-optation and commodification, but it also meant that trans people were increasingly empowered to tell their own stories on their own terms. “I think that moment can accurately be described as a tipping point in trans autonomy and agency, where gender-diverse people could finally speak for ourselves and follow our own trans trajectories,” Serano says.

On a practical level, this meant that trans people could spend less time explaining their own existence to cis people. “Awareness of trans people has exploded,” says Ashley. “When I came out, so few people were aware of trans existence and I constantly had to explain myself and do the most basic of education with people. Nowadays, it’s something I’ve been able to treat as a matter of course in most settings.” Willy Chang Wilkinson, an LGBTQ2S+ cultural competency trainer, affirms that he “has observed a positive transformation in the cultural competency of health providers, educators, business professionals, journalists, legislators, artists and the general population.”

Increased visibility also meant that trans people could use mass media to speak about their lives, rather than just being spoken about. This shift becomes apparent when you look at the TIME article—it’s badly dated, and potentially even offensive in some places. Wilkinson, who was enthusiastic about the article at the time, says he was “disturbed” upon rereading it recently: “what many viewed as respectful then is inappropriate now.” Walker points to the irony that one of the supposedly defining articles about trans rights was assigned to a cis journalist.

“Trans-authored work is just so much more accessible than it was 10 years ago, regardless of where you live,” she tells me. “Like, you’d have to be really fucking stupid or disingenuous to claim that there are no trans writers, artists, filmmakers, designers, singers, entertainers or whatever out there.”

It’s true: one of the most obvious ways the change has shown up has been in the arts. In 2014, Laverne Cox was probably the only trans actor most cis people could name. In 2024, the number of openly trans actors (Elliot Page, Brian Michael Smith, Jamie Clayton, Hunter Schafer) and trans filmmakers (Jane Schoenbrun, Lilly Wachowski, Theda Hammel, Janet Mock) and trans musicians (Anohni, Arca, Kim Petras, Ethel Cain) and trans authors (Torrey Peters, Akwaeke Emezi, half of the people quoted here) who have come out or begun their public careers in the past ten years is too large for any one article to list them all.

The biggest marker of progress is that—in the world of entertainment, at least—trans people have come to seem unexceptional. So many TV shows have rushed to cram in a Socially Relevant Trans Plotline that they’ve stopped registering. (I think the anguished transmasculine coming-out scene on Netflix’s Sabrina the Teenage Witch reboot was where I lost count.) There have been so many “first trans person to ____” stories (first trans state senator, first trans New York Times bestseller, first trans America’s Next Top Model contestant, first trans Boy Scout, first openly trans gondolier who also knows Juliette Binoche, etc.) that it’s probably more surprising not to be the first trans person to have done something. Hari Nef played a Barbie doll in a movie that made a billion dollars. We’ve had both a trans Miss USA contestant and a trans woman on the cover of the Sports Illustrated swimsuit issue, and, crucially, neither story was a huge deal. (Dylan Mulvaney’s face on a beer can, on the other hand …)

The problem is that this increased media visibility didn’t translate to increased safety or respect in the real world. There’s a long history of the dominant culture accepting minorities as entertainers while not really accepting them as people, and a “tipping point” that happens only in the media may as well not have happened at all. The trans tipping point “always felt to me more like a media creation than an actual social shift,” says media critic Parker Molloy. “Despite the fanfare, we never really received the social recognition or legal protections that should have accompanied such a ‘tipping point.’” Instead, someone arrived to wipe out what little we had gained.

Backlash

The TIME cover was published in May 2014. “Just one year later,” Jamison Green says, “Trump glided down his gilded escalator, and it was clear to me we soon would be fodder in his supporters’ power struggle.”

Trump—also pretty popular in mainstream entertainment, for what it’s worth—represented a new strain of Republican politics, openly aligned with extremists and fed by culture war. As the latest minority to be dubbed newsworthy, trans people naturally found themselves in his crosshairs. It was the beginning of a legislative and cultural backlash that has only escalated over the past eight years, even under the nominally Democratic presidency of Joe Biden. “We are still fighting for our lives and the right to live as human beings in safety,” says activist Jevon Martin. “Politicians are taking away our rights to have agency over our own bodies. The anti-trans bills are at an all-time high. Trans rights are under attack and the silence from [the] community is deadly.”

This was a predictable turn of events, and—as Ashley reminds me—trans people of colour had been warning against it for years. “As Black trans activists and scholars like Tourmaline, Che Gossett and Juliana Huxtable have taught us, visibility is in many ways a trap,” Ashley says. “It doesn’t bring benefits nearly as much as it places a target on your back, and that’s a particularly visceral lesson for us.”

“A handful of people were given opportunities, the greater queer community embraced us more, people thought trans people would be okay,” says Feder. “We became a commodity—and it didn’t take long to lose our value.”

The speed and cruelty of the backlash has been shocking for many people. “I could not have predicted that 10 years later, gender-affirming providers would regularly receive death threats, supportive parents would be threatened with the removal of their kids from their care and our basic human rights would be severely restricted in schools, healthcare and throughout society,” Wilkinson says. Ashley has also seen the state of their field devolve in the decade since the tipping point: “When I started doing scholarship in trans health, the frontline of debate was trying to leave behind gatekeeping and move us toward informed consent; now, the challenge is to even keep trans healthcare legal,” they say. “It’s hard not to lose hope.”

The very visibility that trans people were promised has started to wither as it becomes risky to align with or support us. “The media, once eager to spotlight our stories for clicks and headlines, has largely abandoned us, leaving trans people to fend off a wave of hostility on our own. It feels bleak,” Molloy says. “It feels like we’re on our own, and I just have a hard time imagining things getting better in the near future.”

“We were not ready,” Green says. “We were not mature enough in our politics to withstand those attacks, and while we have fought back valiantly, most of our political strength has withered. Already we have lost more than we gained over the past 30 years, before we had explicit civil rights, access to medically necessary healthcare and recognition under the law.”

There are days when it seems that the tipping point’s only legacy is fear, hopelessness and loss of our prior gains. Yet it would be cruel to leave you there. Even as we’ve come under attack, we’ve gained each other, and a lot of new friends.

Trans tipping point II: A new hope

“I don’t need to tell you the myriad ways things have gotten worse,” Serano tells me. “What has gotten better is that many people do support us now.”

Getting the basics of trans existence and experience into the mass culture may have attracted the attention of bigots, but it has also allowed us to connect with supportive cis people to an unprecedented degree. It’s become de rigueur for cis people who consider themselves leftist or progressive to support trans rights. The number of middle-aged white cis guys with basically acceptable trans politics is not something I could have predicted in 2014, or 2020, for that matter.

“When I transitioned back in 2001, most people didn’t know any trans people personally, and the rest were indifferent or antagonistic toward us,” Serano says. “The ‘Tipping Point’ cites a survey that found that nine percent of Americans at the time knew someone who is trans. A Pew Research survey from 2021 showed that that number has increased to 42 percent.” Polling has shown for years that when straight or cis people know queer people, they are less likely to support discrimination against us—for instance, straight people who knew at least one gay person were more likely to support gay marriage.

There is also the fact that trans people can now see and hear each other much more easily. “We are more numerous, united, networked and resolute than ever,” says Cross. “Despite all the despair and drama online, what I see in the world of activism is a lot of commitment, allies and the building of power.” Becoming a ubiquitous topic of “debate” has, at least, forced more people to stake out a position on our humanity, and it is now common for mainstream Democratic politicians to at least pay us lip service, as, for example, in the Biden administration’s redefining Title IX to more aggressively cover trans students’ rights. “Over a decade ago it would’ve been unthinkable for it to be a mainstream Democratic Party policy position to support trans rights,” Cross tells me, “and yet here we are.”

Yes, here we are: more visible, less powerful; more known, less loved; more seen, less safe; but here, known to each other and the world, in ways that would have been unimaginable a decade back. We have the ability to be more than just a marketing demographic or a news trend, to use the blinding spotlight aimed at us for real good. The trans tipping point, Cross reminds me, “was always a contradiction,” and we are still living out both sides of it: “It’s up to us and to our allies to ensure that we do not tip into the abyss.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra