“Writing about music,” it’s been said, “is like dancing about architecture.” It’s hard for a novel to convey what music can do to a person when that feeling is so subjective and the delivery method is the silent printed word but books like Nick Hornby’s High Fidelity and Oscar Hijuelo’s The Mambo Kings Play Songs of Love tackled this with style. They’re now joined by Mouthquake, the slim but potent new novel from Montreal writer Daniel Allen Cox.

In his acknowledgments, Cox thanks the Grand Antonio “for letting your weirdness shine.” He exists, then?

“He existed, and he exists,” Cox tells me, “I met him when I was very young, when he patted me on the head one summer. I won’t go into a detailed bio here, because a more accurate record of his life can be found online, but he was a Croatian-Canadian strongman, wrestler, immigrant, actor, mystic, and resident of the streets at different periods of his life. He spoke with his own kind of fluency, his own rhythms. In a larger context, we all communicate to each other on different frequencies. It will probably take a lifetime to learn how to recognize each other’s signals for what they are.”

This is the journey that Mouthquake takes Cox’s narrator and we the readers on — learning how limited we can be in communicating with each other yet how vast our options for doing so truly are. When the narrator meets a deaf man named Eric in a club, their love story becomes the complicated heart of the book. While many novels feature romances that fumble toward an eventual joy of connection, Cox’s lovers here find that bliss is only the start of something more raw and troubled, more real. Eric and his new partner challenge each other (and the reader) in tough and surprising ways.

While early chapters of the book play with our sense of time and narrative, featuring improbable cameos from celebrity musicians and a wintry Montreal dreamscape, Cox really lets loose midway through with a thrilling sequence of chapters riffing on record thieves, penises, branding, grocery shopping, the Book of Daniel, scat, iPod headphones and a truly terrifying millipede. His imagination is wild and expansive, yet even as he approaches the dark realms of William S Burroughs, the journey remains soulful and introspective. We are touring the contents of his narrator’s head and it’s fascinating.

“I wrote this book in such an oblique way, in a kind of channelling that I later pieced together,” Cox explains, “The result is that certain elements are wide open to interpretation. I like how this lets writers and readers become better collaborators, and I fear that stating my intentions can sometimes diminish that exchange.” All he’ll say about an early chapter featuring a grand and troubling “Open Letter to the People of the City of Montreal,” for instance, is that “I was probably thinking about the ways people can collectively suppress a marginalized voice, or voices that take more effort to understand.”

“Daniel slices open the experience of experience, sometimes with insight, sometimes with threat,” writes Sarah Schulman, author of the classic Rat Bohemia and the vital Gentrification of the Mind, in her generous afterword in Cox’s novel. Most writers hope for a simple blurb from their heroes so Cox must’ve been thrilled by her essay.

“I was blown away when I first read it, and still am,” he says, “It’s an emotional experience and an honour to receive an afterword from one of your favourite writers, and someone who is a mentor and friend. I’ve always been in awe of the important conversations that her work creates. I’m thankful and looking forward to our upcoming event in New York together where I will get to hear Sarah read it in her voice! And can’t wait for her new upcoming work.”

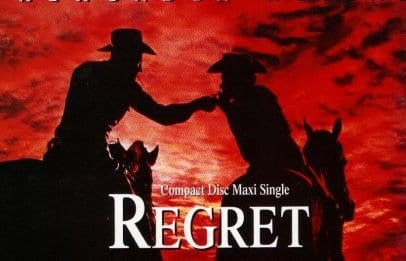

Like much of the music it references (even Hall and Oates!), Mouthquake is full of soul and throbbing, wit and darkness. One sequence is an extended love letter to New Order, a band that found new glory after a horrifying suicide, and Cox plays special homage to their song “Regret,” masterful in how it hits high joys and deep melancholy at once.

“Seriously,” he agrees, “I used to volunteer at a community radio station, and I remember the day I received the CD single for ‘Regret’ that the record label had sent to us. I was the first person at the station to hear it (on CD, anyway) and because it came in the mail in an envelope, and I was alone, the experience felt very personal, even personalized. It created a moment that lives with me — isn’t that what music does, creates moments?”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra