The subject of same-sex love, as it relates to paedophilia, is fraught with complex emotion. Michael Rubenfeld’s play, My Fellow Creatures, currently running at Theatre Passe Muraille, approaches the issue with sensitivity and a careful eye for what could have become a sensationalized and voyeuristic look at a topic that may never be fully resolved.

The basic premise of Rubenfeld’s treatment posits the question: What if two paedophiles met in prison and began to discuss their opposing views of their respective crimes? Inspired by a news story about two convicted sex offenders sharing a single cell, the play opens with an ominous introduction where the younger prisoner silently approaches his “partner” and interrogates him with an intense, sullen gaze and then exits abruptly. This opening sequence paves the way for what might have been a layered and thought-provoking journey toward a very startling climax.

However, despite the playwright’s valiant intentions regarding a subject that he feels troubles “the nature of desire and where that comes from,” the script quickly becomes a circular morality tale that might have worked better had the fable-like qualities been handled in a somewhat more surrealistic manner.

The stark realism of the overall production is at odds with a style of writing that tends to oversimplify an extremely complex and controversial subject that Rubenfeld ultimately ties up into a relatively neat package of conflict and resolution. As we have seen in many classic literary and dramaturgical treatments of inappropriate sexual intention (like Tennessee Williams’ Streetcar and Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita) this is rarely how desire operates.

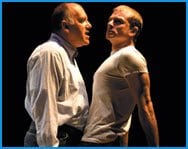

Performances by Benjamin Clost as the younger paedophile and Terrance Bryant as his more mature cohort are committed and passionate attempts to bring dignity to these profoundly flawed men. Bryant’s approach to Arthur, an intensely romantic emotional train wreck, continually rationalizes his behaviour with diatribes on physical beauty and the sincere, mutual affection he shared with his victim. The dialogue, however, rarely enters the territory of boundary issues, a primary area of psychoanalytic thought crucial to the treatment of this particular pathology.

Clost’s approach to Kelly, the younger paedophile, physically and verbally challenges Arthur’s every sentiment, and provides dramatic tension that has some powerful moments. But his lines fall prey to a one-dimensionality that relies upon a form of brutish anger, ultimately sidestepping any attempt to actually understand the very convoluted dynamic that unfolds between the two men.

The third character, a prison guard competently played by Richard Zeppieri, could use some radical reshaping in order to provide a more successful foil for the other two men. As it stands the character acts as a mere chaperone of sorts and never fully develops within the story.

There are brief glimmers of possibility when the ultimate moment of recognition reveals itself. Rubenfeld skillfully alludes to the psychology of aging, intergenerational desire and preadolescent sexuality. But at the end of the day the subtlety is heavy-handed. Rubenfeld should have taken a few more risks in order to raise the stakes and articulate the drama.

In an epigraph Rubenfeld — perhaps unconsciously — reveals a primary problem with his treatment when he states: “People are not bad. Love is hard. This is not a play about bad people. This is a play about love.” At the risk of being judgmental, people often do bad things. As it stands, the current Absit Omen Theatre/Buddies in Bad Times coproduction flounders as it grapples with an aspect of love that in fact does turns “bad” the moment it crosses crucial sexual boundaries that Rubenfeld has not fully addressed.

Promising plot twists and impassioned performances make the production a controversial and potentially viable way in which a play may begin to address such risky business; audiences may be motivated to examine the complexities of the issues further. But in the end My Fellow Creatures merely teases without delivering a completely satisfying conclusion or climax.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra