Daniel MacIvor is a great big tease. He keeps you in a state of constant arousal with the promise of a life-shattering moment in the theatre, an epiphany. This state of excruciating pleasure lasts the entire 70 minutes of his one-man show Here Lies Henry, currently running at Buddies In Bad Times Theatre. That the epiphany never appears, that he offers no release, is one among many satisfying points in this elliptical exploration of death and desire. MacIvor offers no easy answers, only mind-whirring riddles.

The da da kamera play originally from 1996 and again directed by longtime collaborator Daniel Brooks is almost impossible to describe. Reducing it down to its narrative elements won’t help your comprehension and might even lessen the power and pleasure of seeing it for the first time. Outward descriptors of the protagonist, Henry — cosmetics salesman, gay, Canadian, dead — are such mundane bric-a-brac compared to the urgent needs and passions MacIvor evokes through a bravura display of physical ticks and verbal hiccups.

Nothing is obvious; meaning is found in the tiniest things. Everything else is just posturing, lies. We are all the same, Henry says. We are born; we have some experiences; we die.

You don’t believe for one moment that the quivering bumbler who greets you at the opening of the play is anyone but MacIvor himself, the celebrated theatre artist totally in control of his craft. But the character of Henry soon has you under his bitter, guilt-ridden, ever-romantic spell. His merciless insights never miss their mark. A deliciously cynical diatribe on the boredom and petty defeats of connubial bliss, for example, has everyone squirming in their seats.

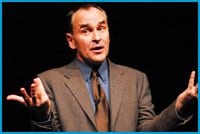

In an empty black space framed only by light, MacIvor’s performance is nothing short of spellbinding. The torrent of words is delivered flawlessly; stories fold back on each other and repeat to illustrate their inner meaning not the outward affect. MacIvor’s delivery is wonderfully punctuated by sound effects or underlined by soundscapes designed by Richard Ferren, all perfectly in synch with the performer.

And what a shameless ham MacIvor can be. When Henry falls into a feedback loop of public speaking errors — “um, sorry, anyway” — both he and the audience revel in how far MacIvor can push it.

MacIvor and Brooks know how to structure a strange piece like this: the positioning of set pieces and purely physical moments, juggling drama, comedy and thoughtful reflection — the pacing is flawless.

Buddies’ opening night audience — notorious for enjoying performances over productions, the man not the meaning — still had its expectations scrambled. MacIvor has much greater ambitions than just a fun night out at the theatre (well, maybe not; it’s complicated). Only he could make what turns out to be an object lesson in Nietzschean philosophy so enthralling.

In this harsh nihilistic vision, nothing exists — not God, nor love or meaning — except what we create. It’s a frightening and lonely worldview. But life, like theatre, is made easier through a few tricks of the trade. Here’s where Henry’s lying and MacIvor’s stagecraft come in handy. Life, like MacIvor’s theatre, is our own creation.

By play’s end, MacIvor has turned Henry inside out and brought the empty outside world into a theatre brimming with ideas. He finishes with an off-kilter but deliriously happy description of the afterlife. Heaven, it seems, is an audience. When he finally spins this comforting deception, that hoary old chestnut that theatre is a collaborative creation by playwright, actor and audience never tasted as sweet.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra