General Idea, P is for Poodle, 1983-1989. Credit: Ryan Faubert

General Idea, AIDS, 1989. Credit: Ryan Faubert

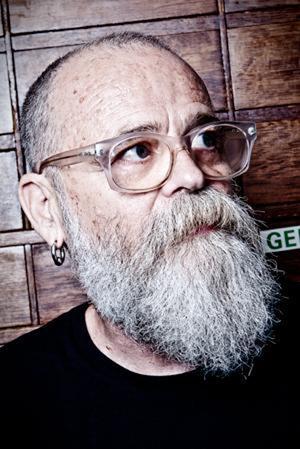

If you’re not exactly sure who or what General Idea is, join the club. The legendary artist trio, composed of Jorge Zontal, Felix Partz and AA Bronson, always made their project hard to crack.

“I think that’s one of the things that made it difficult for General Idea to have quick success,” says Bronson. “Because people could never figure out who we were or what we did. It was changing too quickly.”

Bronson met Zontal and Partz in Toronto in 1969 and made conceptual art with the two until their deaths from AIDS, just months apart, in 1994. Even in their earliest work, the group intentionally confused their audience, creating glamorous and bizarre happenings like the Miss General Idea Pageant. The years-long project consisted of several Miss General Idea Pavilions and Boutiques, false storefronts and showrooms set up in galleries and public spaces and, of course, a series of beauty pageants.

Accompanying the pageant was the pop-inversion lifestyle magazine FILE. Full of flashy and bizarre depictions of a glamorous, largely imaginary high-art society, FILE enhanced and elaborated General Idea’s mystique to an unprepared media and public.

Amid the spectacle, most attempts to pigeonhole or label the group didn’t stick. Yet there was an eerie media silence about the one thing that was quite clear about them: their queerness.

“[Our work] can be looked at and analyzed in terms of a queer context, everything we did from the word ‘go.’ But back in the ’70s, if you called yourself a queer, your career would have been pretty much over,” says Bronson.

“We were criticized by some Toronto artists for not calling ourselves gay artists, but we pushed the envelope to get the media to recognize us as queer artists, and the media refused to, in a sense.”

Even when General Idea premiered their Mondo Cane Kama Sutra (1984), a series of enormous paintings of neon-coloured poodles engaged in comically complex sex acts, The Globe and Mail strangely praised the pieces as a metaphor for artistic collaboration.

“They were 100 percent recognizably queer,” says video artist John Greyson, who first encountered General Idea when he moved to Toronto in 1978. “Theirs was an absolutely confident, crazy queer sensibility that almost put quotation marks around ‘camp.’”

By the time of the AIDS crisis, it was quite impossible to ignore General Idea’s dedication to a queer politic. The trio moved to New York in 1986, where their first big project garnered an international response. The AIDS logo was an appropriation of Robert Indiana’s famous LOVE logo, revised to read “AIDS.” The image was spread in endless iterations around New York and across Europe, and the group was accused of irresponsibility and insensitivity. Yet the message resonated in the queer and arts communities.

“When they did the AIDS logo, it was a perfect symbolic gesture trying to make some sort of linear link between the political queer sensibility of AIDS activism and a strong art aesthetic,” says Toronto filmmaker and artist Bruce LaBruce, who, according to Bronson, expanded on some of General Idea’s work on queer identity.

As General Idea moved into the ’90s and Zontal and Partz became more ill, the group focused almost exclusively on the iconography and politics of the AIDS crisis, from public installations of blimp-sized AZT pills to self portraits of the artists as vulnerable seals or doctors. When Felix died in June of 1994, Bronson took a final and absolutely harrowing portrait of his recently deceased friend in a colourful hospital bed.

Since then Bronson has gone on to have a successful solo career. His work has largely focused on death, mourning and memory. But as effective as General Idea’s AIDS work was in its time, Bronson, like many, is unsure how to make art about AIDS in the present day.

“To have AIDS posters plastering the street at a time when people are dying right and left is different than doing it now. The emotional reaction and the kind of dialogue it brings up are very different,” he reflects. “It’s hard to know how to deal with the current situation. I’m hoping that younger artists have the answer to that. I was so embedded in that other situation that it’s hard to disentangle myself from that history.”

In a present in which the AIDS crisis and alternative queer identities are too often considered secondary issues, there has never been a better moment to remember how this group of tongue-in-cheek weirdos changed the way we perceived queer aesthetics and politics forever. In fact, that is the very intent of so much of General Idea’s work: to challenge the audience to react.

“It’s [General Idea’s] conceptual practice of throwing it back on our laps and asking us where we position ourselves, daring us to engage, leaving us with the big work to do… That is very satisfying, in retrospect,”

marvels Greyson.

* * *

Haute Culture: General Idea, a retrospective runs until January 2012 at the Art Gallery of Ontario. For more on the exhibition check out Xtra‘s story here.

Watch the online conversation between Bronson and Valelly below.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra