Weighing in at an economical 260 pages, Michael V Smith’s elegant and spare second novel still manages to meditate on profound themes.

Set primarily in a small Ontario town facing momentous change — its residents and their homes are being relocated to make way for a new dam — Progress is a moving account of the difficulty of transformation and the anxious soul-searching that often accompanies personal evolution.

Robert and Helen, two estranged siblings, are the focus of Smith’s story. They are reunited days before the physical site of their past is about to be flooded forever.

Robert, an addict in recovery, ran away to Ottawa when still a teenager and fell into drugs and random sex with men. In contrast, his sister never left town. Having cared for her parents during their fatal illnesses, Helen seems permanently stalled, firm in her (false) beliefs about her brother’s death and that her happiest days have long since passed.

Estranged for a decade and a half, it’s a given that the opening hours of the pair’s reunion are neither comfortable nor successful. Between them stand old but powerful secrets and lies (not to mention a destructive romantic quadrangle).

In the arcs of their stories, Smith examines complex ideas — anger and forgiveness, the crushing weight of the past, the possibility of finding happiness in an often-ungenerous world.

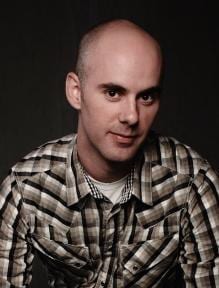

Smith found acclaim with the 2002 publication Cumberland, his first novel. He gained wider fame as a multi-disciplinary artist whose undertakings ranged from short films and poetry to co-producing the Odd Ball and gallivanting as Miss Cookie LaWhore, a drag persona with a singular mandate: pleasure over fear.

More recently Smith added “assistant professor” to his portfolio, and he’s now teaching at UBC Okanagan in Kelowna.

People who’ve been exposed only to Smith’s flamboyant performer side might be surprised at both the tone of the novel and its setting. Smith says the town setting of his two novels is an outgrowth of his own past.

“I grew up in a small town, and I think I’m very much a product of that. Sure, I have big-city tastes, but I talk small town, my family is all small town, and my politics are deeply wrapped up in the prejudices I was witness to those years ago.”

Where does the sequined, in-your-face aspect of Michael V Smith disappear to in his novel?

“We’re complicated,” he replies.

“I get to be outrageous and quiet and deep and goofy. None of me needs to disappear to pull that off,” he elaborates. “I just get to be myself: I’m a serious novelist. I write serious novels. I wouldn’t say that serious makes it sombre — any more than I think these characters ordinary.

“Everyone’s remarkable. That’s part of the job of what art tries to get us to understand, yes? We are all remarkable.”

Progress links Robert’s adolescent traumas to his eventual promiscuity and drug problems. Asked if his novel is making a case for a direct link between childhood unhappiness and gay male promiscuity and drug usage, Smith points out that he’s no sociologist.

“Everyone has to come to terms with her or his childhood to become an adult,” Smith says.

“Being fucked up isn’t a gay thing. Helen’s sheltered life isn’t any happier than that of her brother,” he notes.

“I’m not as interested in the causal connections as I am in the human drama, the stories we tell ourselves, the ways we move through the world to try to better our lives,” Smith adds.

“Who cares about the cause? I want to find the solutions. And if not the solution, the balm.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra