Actress Lisa Ann Walter is in fashion nowadays, with a wealth of well-deserved love for her latest character, a fiery Italian with a spiky facade and the biggest of hearts named Melissa Schemmenti, on the critically acclaimed ABC mockumentary Abbott Elementary. But let us not forget—especially those of us who are ’90s kids—the origin of our adoration for Walter. Walter herself certainly won’t have that—her Twitter bio still carries the tag: #ChessyForever, referring, of course, to the famously beloved nanny in the 1998 Disney classic The Parent Trap, which will soon celebrate its 25th anniversary. If you didn’t religiously return to your local home video rental store and wear down their copy of The Parent Trap as a kid, we’re not the same. The movie that made Lindsay Lohan (welcome back, we missed you!) also made me. And by god, it’s true what they (Fleetwood Mac) say: even children get older, and I’m getting older too. But The Parent Trap remains a comfort watch for a generation of ’90s queers.

In a recent interview on The Jennifer Hudson Show, Walter revealed, as she’s done in many other interviews, the depth of love that ’90s kids (now, I suppose, adults) have for The Parent Trap, and specifically, Chessy. She says that she still receives comments disclosing that watching this movie makes people feel safe. “Especially,” she continues, “from kids who in those years felt a little … like their lives were not as safe, or they weren’t as accepted, like, kids from the LGBTQ2S+ community still write me now and say, ‘You made me feel accepted. You made me feel good. You kept the twins’ secret and you made me feel like if you were in my life, I would have been loved.’”

As an only child of divorce, and a queer kid, this rings true to me. At a time when my life felt scattered and incomplete, the fantasy world of The Parent Trap, and the warm and maternal presence of Chessy, provided me with a dream of gluing the pieces of it together. The film, though not explicitly queer, still provides a sort of utopia of queer acceptance, connection and love.

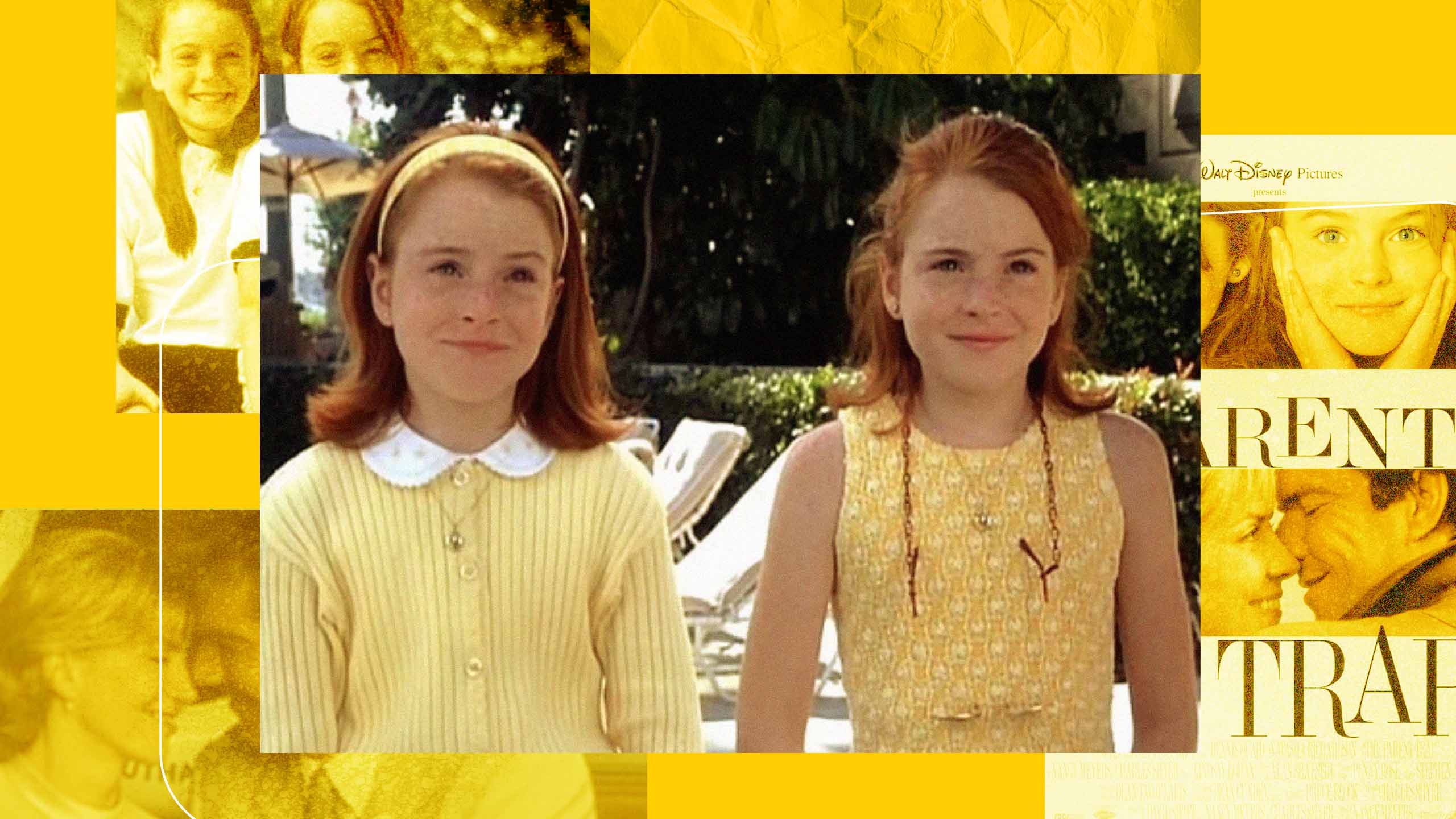

It is admittedly a bit odd that The Parent Trap has become a queer classic, considering the film’s premise. The basic plot of the movie—which is based on a children’s book by German author Erich Kästner, and a 1961 film by the same name—follows twins Hallie and Annie (played by the singular Lindsay Lohan), who meet at a summer camp and figure out the secret that each of their parents has kept from them throughout their lives: they were separated at birth. Each was raised by their divorced parents away from one another—father Nick (Dennis Quaid) took Hallie to Napa, while mother Elizabeth (the late Natasha Richardson) took Annie to London. Now, putting the pieces together, the twins decide to reunite their family—by first reuniting their parents. The first step of the plan is to go back to their respective homes as one another: Nick gets Annie, who’s pretending to be Hallie, while Elizabeth gets Hallie, who’s pretending to be Annie. When the parents find out, they will have to meet again to make the switch, with the juvenile hope in the twins’ heart that they will immediately fall back in love. And eventually, after some drawbacks that demand the twins engage in more shenanigans to achieve their mission (namely, they must face the presence of a classic Disney trope, the Evil Stepmother, Meredith Blake, portrayed by the deliciously camp Elaine Hendrix), they do.

Many heteronormative notions of family are raised by this premise: the inherent importance of a genetic connection and the superiority of the nuclear heterosexual family come to mind. At the time of release, Christian movie reviews picked up on those and praised the film for it, though perhaps they have been a bit misguided in their appreciation of the film, which also carries proto-feminist messages that empower young girls and women to go after what they want, as producer Charles Shyer notes.

Still, The Parent Trap is a formative influence on queer audiences, from Walter’s performance as an accepting accomplice of the twins, to the fact that everybody wants to live in the comfortable fantasy of a Nancy Meyers film. But there is more queerness to The Parent Trap than meets the eye.

To start, The Parent Trap is literally queer. If the name “Tie-Dye Girl” rings any bells for you, you are probably queer, online and a fan of The Parent Trap. Often, the internet reads Tie-Dye Girl as Hallie’s summer-camp girlfriend, and they have every reason to do so. Tie-Dye Girl’s first appearance in the film sees her pulling a duffel from beneath a giant pile of other heavy duffels with ease, prompting Hallie, who is struggling with her own duffel, to say, “Now that’s my kind of woman.” After helping Hallie with her bag, Tie-Dye Girl and Hallie become inseparable. Another scene sees Tie-Dye Girl carrying Hallie piggyback style and calling her “babe.”

I know I certainly aspired to be Lindsay Lohan as Hallie in The Parent Trap long before I came out of the closet. She was fun, sporty, cool and she had Tie-Dye Girl by her side. This movie speaks to a lot of Sapphics precisely because there is something so casually and joyfully gay—and aspirational—about Tie-Dye Girl and Hallie’s relationship.

The Parent Trap has more to offer queer audiences than implicit clues, though. One of the most charming scenes in the film comes when Hallie, the unbeaten fencing champion of summer camp, is challenged by Annie, who ends up kicking her ass in fencing. It’s the first time the twins come face to face with one another, seeing their own likeness, and as they shake hands, something passes between them, something inexplicable. Hallie recognizes herself in Annie, and Annie recognizes herself in Hallie. This moment is akin to one many queer people experience in their lives: the first time we feel like we are known through knowing someone else who is like us. It can be as simple as seeing ourselves represented on screen, or as complicated as entering a queer space for the first time. It is the piecing together of ourselves through the presence of another. It’s kinship.

I used to dream of finding a lost twin like Lindsay Lohan, about putting the pieces of my life back together by refitting the torn-up image of my parents’ divorce together.

Following this scene in the film is a prank war that lands the twins in the isolation cabin, where they put together the clues that have accumulated during their short acquaintance. We then get the iconic image of the twins refitting their parents’ torn-up wedding picture. As Hallie and Annie learn more about one another’s lives, they also learn more about their own. They understand themselves and their histories better by understanding their mirror image. The twins discover a more complete self by learning that there is someone out there who is just like them. This is an extremely queer occurrence, and it explains so much about why The Parent Trap comforts us queer millennials: it is the same sense of “twin soul” that the queer community, the queer chosen family, provides for queer people. And if you’ve watched the film before you’ve experienced that, or even after, of course you’d be drawn to it.

Finally, let’s return to Chessy. A broader, more metaphorical level of queer reading in The Parent Trap revolves mainly around one iconic scene in which Annie, pretending to be Hallie, reveals herself as Annie to Chessy. Chessy embraces her after giving one of the most emotionally satisfying speeches of acceptance that any gay kid could ever hear. When Nick, the girls’ father, who is completely out of the loop, finds Chessy and Hallie (Annie) right in the middle of their conversation regarding Hallie’s (Annie’s) identity and asks Chessy why she’s looking at Hallie (Annie) “like that,” (meaning looking at her weird, because Chessy just discovered the truth), Chessy tearfully replies, “Like what? I’m not looking at her in any special way, I’m looking at her like I’ve looked at her for 11 years. Since the day she came home from the hospital … 6 pounds, 11 ounces, 21 inches long, this is how I look at her! Can I hug her?” And with Hallie’s (Annie’s) approval, she does.

Though Hallie (Annie) has revealed a secret identity, that secret identity has not changed an ounce of the care and love that Chessy feels for her. On the contrary. She quite literally embraces her. It’s a dream coming-out moment.

I used to dream of finding a lost twin like Lindsay Lohan, about putting the pieces of my life back together by refitting the torn-up image of my parents’ divorce together, easing my loneliness within that situation as an only child—torn up between my parents—by finding a kin. That dream died a long time ago, especially as I grew up and came to terms with my queerness, which has helped me come to terms with the idea that it wasn’t the “wholeness” of a heterosexual nuclear family that I was after—it was the sense of community and understanding that I eventually found through being queer. What didn’t die, though, is the sense of comfort that the fantasy world of The Parent Trap provides me. Some days I still think that maybe all I need is a hug from Lisa Ann Walter and I will be all right.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra