Red Carpet.

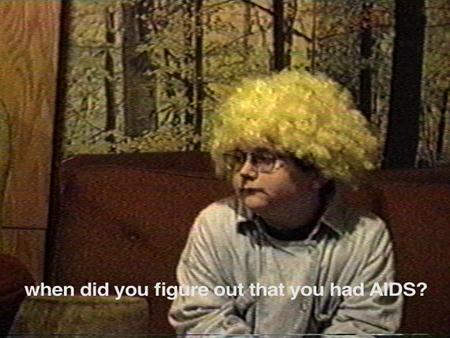

'So when did you figure out that you had AIDS?'

Fellini once said that all art is autobiographical, while Camus said that all art is confession. Both of these quotes could easily be ascribed to Vincent Chevalier.

“Disclosure is a huge part of my everyday experience,” he says. “It structures how I relate with people, the state, myself.”

Those disclosures encompass his life as an HIV-positive gay man living in the 21st century. It is a life marked by sex, the internet and the politics that lie therein.

Born and raised in Montreal and its environs, Chevalier went to the National Theatre School as a teenager but felt limited by the options presented to him there. At 19, he discovered that he was HIV-positive. It was around this time that he started doing performance art, which garnered him some media attention. In 2006, he was featured on the cover of Xtra during the World AIDS Conference held in Toronto; the image was of him, with the words “I am AIDS” written underneath. Chevalier enrolled in the fine arts program at Concordia, where he found inspiration in the work of artists and collectives such as Marina Abramovich and General Idea.

After finishing school, Chevalier continued to work in performance art. With The Red Carpet Treatment, he marks his path by walking every step on a two-metre slip of red carpet. He treks across cities such as Montreal and Kuopio, Finland, never letting his feet fall off the predestined path. In Blank Hanky, Bottom Right, Chevalier’s own ass is the medium on which his art is displayed. Tattooed on his right ass cheek is the outline of a handkerchief, a nod to the hanky code used among certain gay men to silently declare sexual desires and appetites.

“My work is about trying to disclose all the things with action that I could never disclose in words,” he explains. “The idea behind the tattoo is that it was left blank so that it can be coloured in by someone else, depending on what sex act they want to do with me.”

The tattoo is another form of disclosure, not only of Chevalier’s openness to sexuality, but to the sexualities of others. But Chevalier’s oeuvre isn’t confined to only performance and body-based work. It also encompasses installations, websites and videos. Much of his work is self-referential, but it would be wrong to accuse him of being narcissistic. Chevalier uses himself as a mirror for the experiences of 21st-century gay men, with part of that experience determined by the disclosure required of gay men in today’s society.

“Disclosure is an exchange; it’s part of a conversation. It is also a way of marking difference,” he says. “My practice is based in examining my relation to the other through disclosure. In some of my works this action is quite literal: I disclose my queerness, my HIV, my history.”

That history is probably best represented by a video entitled So When Did You Know You Had AIDS. The video is of a young teenaged Chevalier pretending he is on a talk show talking about AIDS. Chevalier recalls shooting the video as a teen, as part of a series of talk shows he and a friend made with a home video camera.

“I think we quickly realized that we had crossed some sort of line when we shot the AIDS episode,” he recalls. “Maybe it was because the subject matter was so intense, but I think the unspoken elephant in the room was that I was obviously a queer kid. And as a young queer kid growing up in the ’90s, AIDS was a terrifying reality that society told me was gonna be my fate.”

Chevalier forgot about the talk-show videos until he found them after his HIV diagnosis.

“I remember sitting in the video transfer studio, having lived with HIV for the previous six or seven years of my life, watching the tape in disbelief. It was an uncanny and terrifying moment of identification with that young version of me on the television screen. The question, ‘So when did you figure out that you had AIDS?’ really came to stand for so much of the complicated and conflicting questions about who I was and what I was going to be that I experienced growing up queer.”

Recently, Chevalier went online to discuss his experience. His website, Places Where I’ve Fucked (PWIF), is a collection of Google Map screen grabs to places where he has hooked up with other men, the images sub-titled with hashtags – #bttm, #oral #w/s – describing the various acts that happened. It’s an intensely honest depiction of queer male sexuality in the age of internet hookups.

This is no accident. Chevalier spent a lot of time online as a teenager growing up in the suburb of Morin Heights.

“It was the way I came into my sexuality, not so much from researching the web – asking, what does it mean to be gay? – but because I started cruising for sex with other men as a 13-year-old kid,” he recalls. “The fact that I grew up cruising the internet for sex at an early age and that now I have this project where I am using these online tools to create this visual archive of my sexual history feels really relevant to contemporary queer identity.”

PWIF isn’t Chevalier’s only online oeuvre. He recently started a Tumblr blog called HFML, or Hyper Flesh Markup Language, filled with what he calls “standard gay boy Tumblr. Very faggy with lots of porn, GPOYs and a smattering of art stuff.”

The title refers to hypertext markup language, or HTML, a code used in websites. For Chevalier, queer life is already coded, with hankies and hashtags for sexual acts, but he thinks that “it’s apt that the internet is just a pile of code that produces these virtual interfaces through which we interact. Our ways of communicating, of finding community, of getting fucked, of defining who we are, are loaded and coded onto the web. We have always been virtual. Now it’s just more obvious.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra