They are everywhere in his plays and yet nowhere to be seen. They are ghosts; with a penchant for committing suicide, they are dead, long before the curtain rises. And one of them is literally eaten alive on a Mediterranean island by a bunch of local boys.

Who are they? The homosexual characters in the plays of Tennessee Williams, the US’s most produced and controversial gay playwright in the twentieth century. He is the man who brought homosexuality and male worship to postwar American theatre and film – albeit in the most ambivalent and disturbing ways.

Long before there was a closet, Williams’ gay characters were locked away safely in it. Their coming out is an act of exposure, a secret that other characters try to sweep under the domestic carpet.

Williams’s peak creative period was a politically conservative era, the late 1940s and ’50s, the time of Senator McCarthy’s witch hunts. Homosexuals, like communists, were considered subversive anti-Americans. That Williams even broached the subject is a courageous personal and literary act. His string of now-classic plays most of them adapted to film by the cinephile Williams, himself include The Glass Menagerie (1944), A Streetcar Named Desire (1947), Cat On A Hot Tin Roof (1955), and, among many others, Suddenly Last Summer (1958).

Nowhere is Williams’s gay representation, in all its ambiguous glory, more fascinating than in A Streetcar Named Desire. A revival by Canada’s award-winning theatre company Soulpepper opens this week at du Maurier Theatre Centre. The obvious homosexual character is Allan Grey, Blanche DuBois’ phantom husband referred to as the “boy I married” by Blanche to emphasize his immaturity – whom she catches with another man and publicly humiliates, leaving him no option but to kill himself. Blanche embarks on a life of promiscuity and prostitution until she meets her match and, as it turns out, destroyer, in her brutish brother-in-law Stanley Kowalski.

Critics have argued that the conflict between Blanche and Stanley dramatizes a struggle within Williams. Williams concurs: “I was and still am Blanche,” he once wrote, adding, “I have a Stanley in me, too.”

The play makes no secret about Blanche’s sex life and dependence on the “kindness of strangers.” Queer criticism has championed her as the patron saint of promiscuity. John Clum, the foremost critical interpreter of Williams’ homosexual themes, goes as far as calling her “the quintessential gay character in American closet drama.”

Stanley’s masculine allure and sexual appetite aligns him closely with, as another critic delicately phrased it, “the gay penchant for rough trade.” His is the untamed masculine presence male sexuality in all its penetrative, phallic rawness immortalized by Marlon Brando’s iconic performance in the film version that Blanche finds both attractive and repellent.

Not one but three dead homosexuals hover over Cat On A Hot Tin Roof. The action takes place in a room “haunted by a relationship that must have involved a tenderness which was uncommon,” a reference to the relationship between Peter Orchello and Jack Straw, the two men that once owned the contested Plantation in the play. It’s now the bedroom of Brick Pollitt, paralyzed, physically and morally, after his “friend” Skipper commits suicide.

The homosexuality of Brick is more pronounced but is still mired in innuendoes and denials. Even Maggie, Brick’s tough wife, refers to it as one of “those beautiful ideals, things they tell you about in Greek legends.” The natural reaction of a closeted, anxiety-riddled homosexual is to go on the attack: during a confrontation scene between Brick and his father, Brick refers to Straw and Orchello as queer, fairies and sissies.

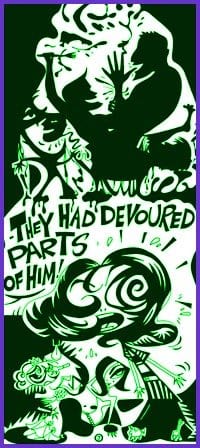

For a dramatization of the social anxiety surrounding homosexuality in the 1950s, look no further than Williams’ surreal play, Suddenly Last Summer. Sebastian Venable is another dead gay character when the play opens. His life is reconstructed through a conflict between his cousin Catherine and dominating mother Violet. When his mother outlasts her usefulness as a bait to attract young boys, Sebastian enlists the help of younger, more beautiful Catherine.

On a trip to the Mediterranean, the racially superior, white-clad Sebastian sexually consumes poor, local boys. Sebastian gets his comeuppance when the boys rebel and eat him alive. Homosexuality is linked to martyrdom and sacrifice with references to St Sebastian and other religious metaphors throughout the play – and to sexual consumption. These are the sacred and profane poles of Williams’ imagination.

The play reinforces Williams’ belief in sex as consumption, and introduces racial difference into the mix. Sebastian, Catherine says, was “fed up with dark ones, famished for light ones: that’s how he talked about people, as if they were items on a menu.” Call it an early case of shopping and fucking.

This equation is illustrated in one of his criminally neglected early short stories, Desire And The Black Masseur, written in 1946. This homoerotic tale of sadomasochism and racial fantasy confirms the theory that Williams made a firm distinction between the private act of reading and the public nature of performance; on paper, he could take risks that the American stage was unwilling to venture into.

Anthony Burns is another boyish looking white man with an overwhelming desire to be “devoured.” He finds the perfect release for his desire in the baths, at the hands of a black masseur who gives him rough massages that function as both sexual fulfillment and punishment for his illicit desires.

The story proves that Williams needn’t create a gay character to exercise his most intimate, homoerotic fantasies. The sexually adventurous playwright admitted that he “cannot write any sort of story unless there is at least one character in it for whom I have physical desire.” Sexually potent studs abound in many of his plays, and they too often meet tragic consequences. Val Xavier in Orpheus Descending and Chance in Sweet Bird Of Youth are cases in point. Both are studly gigolos who drive women crazy with desire. The former is murdered by the town’s men and the later is castrated by a jealous husband.

Williams didn’t come out publicly until 1970 – on the US TV program, the David Frost Show, of all places. There’s an argument that his coming out coincided with his least interesting work on stage (although his fiction got better). Stifling as the closet is, its tensions and conflicts may have been his creative muse. He died in 1983 at the age of 72.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra