A woman awakes. In the opening of her eyes, the room in which the woman sits, and the presence of the woman herself, come into existence. The scene becomes solid and the narrator becomes a person only when she sees the world for herself. The narrator arrives into a world of violence. There is a man in this room who is there to kill her. The man is gross! He slobbers like a dog, sweats, has matted hair, ragged breath, “tiny buggy eyes.” The man tightens the bonds on her wrist. He carries a knife “freckled by rust, dull and dirty.” The woman has no sense of herself before being in this room. Her life is simply now with this man surrounded by “miserable walls” home to “hundreds and thousands of timid bugs.” She constructs herself in this horror. “I became myself as a hook, scraping and tearing, wrestling with the new reality I found myself plunged into.”

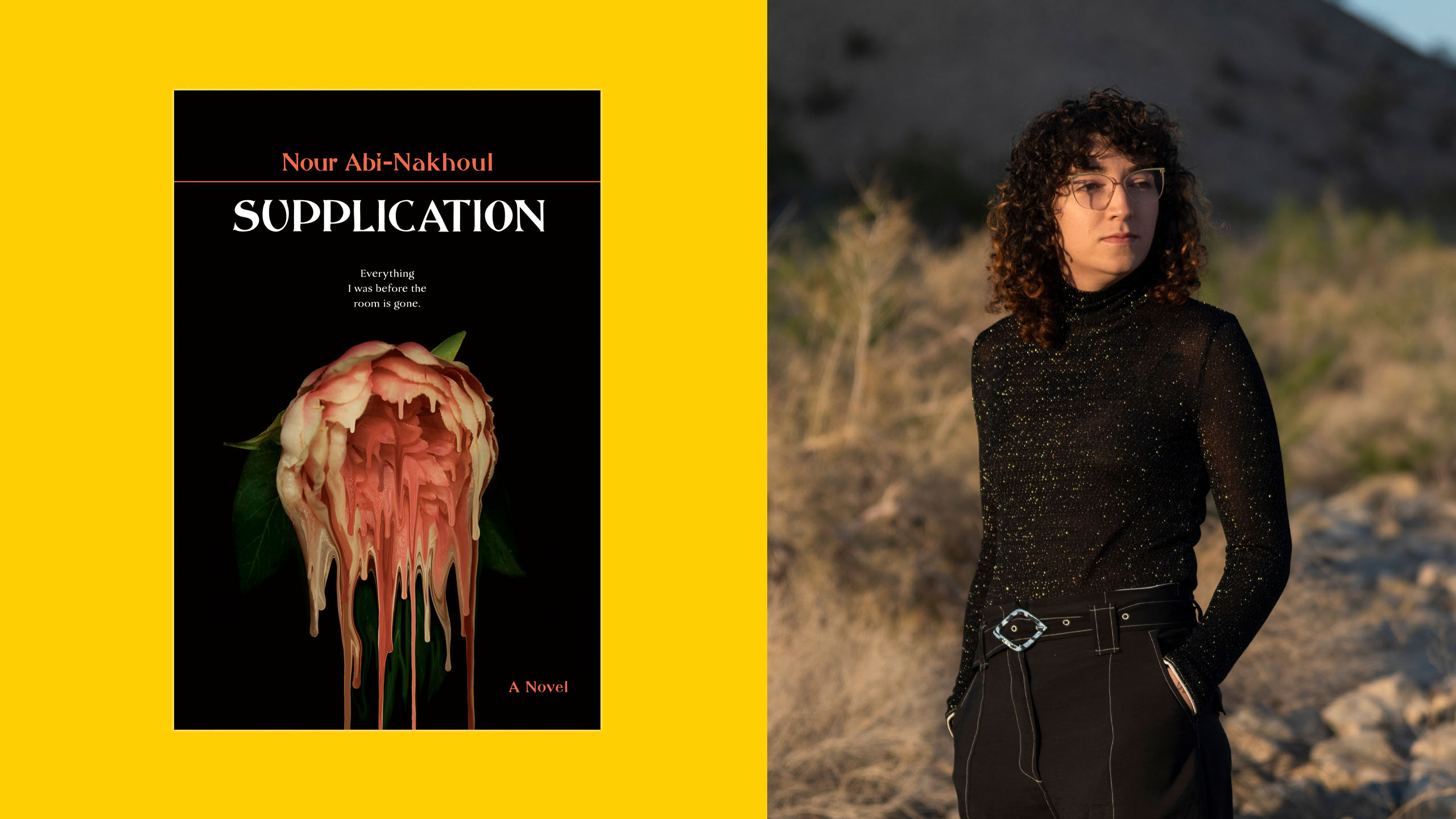

In this novel, Supplication, Xtra contributor Nour Abi-Nakhoul’s debut, the author plays with her narrator’s agency in the clawing construction of her personhood and image. Supplication is a blood-and-guts horror novel mixed with a deeply lyrical narrator. It is about withholding, control, and the malleability of desire.

Early into the novel, the narrator dies in the room with the miserable walls. She is stabbed by the man with the dirty knife, but then returns to us, to this story, and is able to leave. Life continues with further threats, and our understanding of it is smeared with a sickening level of detail. There is, in Supplication, a density both in description and reflection, that matches the novel’s solipsism. Abi-Nakhoul’s approach to description reminds me of critic James Wood’s “hysterical realism,” a term that captured the frenetic detail of late-’90s storytelling. In Supplication, additionally, the world is created—it is fantasy or dreamlike, so readers are never quite able to escape the grimy, bloody vision of the narrator’s perspective. This detail serves two functions. First, as with the disciples of hysterical realism, the description reflects the noise and overwhelmed-ness of contemporary life. Life can be loud, and books, if they are trying to mirror that life, must be too. Second, and more importantly, in the case of Supplication, it highlights the exasperating process of finding agency and control in this world. Supplication asks: What can we do, or be expected to do, to become ourselves in a life that chokes with chaos? At one point, the narrator, in a kind of plea to the reader, says, “That every moment collapsed into itself as soon as it passed, and there was nothing left to hold on to; that all I had were my frail senses and faulty memory, and it seemed there should be more than that.” One way the narrator brings control, or a semblance of it, to her life, is through withholding.

Sometimes I sit with news—both good and bad—and want to hold it close, first, not to share it with friends, not to spoil it with analysis and categorization. Other people, I often think, are just so good at making sense of things! There is a power in keeping the unanalyzed tight within you, where it can stay messy and knotted, free from the limits of our communication. The narrator in Supplication, in a room with two others, decides not to share all of what has happened to her, not to give them “a proper glimpse.” If she did that, “we would have all recoiled in fear, shame, discomfort.” The narrator speaks with an arrogance in this section, doubting that her listeners want to actually know the whole story. Yet, in doing so, she brushes over what the withholding offers her as well. She wants to control their emotional response to her experience. She wants her listeners to feel “fear, shame, discomfort” in just the right way. “The key is to give just enough that all parties are satisfied with the theatre of it, just enough that the illusion is sustained and everyone can continue to play their roles,” she tells us.

There’s also a malleability to desire in Supplication. The narrator decides to make the violence to which she is subject into something that she wants. Something she craves. Her sense of submission and powerlessness to her attacker becomes, in a mental sleight of hand, a feeling of control. The narrator says, “The world wasn’t anything but an arena in which my desire gave form to itself.” Near death, she reflects: “I owned it all.” Desire, and controlling that desire, becomes a way through and out of the vulnerability of the subject’s life. It is as if to say, on repeat, in the midst of the horror: This is actually what I want!

Reading Supplication, I think: Is this meant to frighten? Is this a metaphor? Is this just life? Or: What parts of the novel are fulfilling the rules of the genre? What is here as an allegory to our lives? And how much of the novel is simply telling things as they are? In the delirious nightmare of this novel, I kept thinking about the gaps built in the construction of a story and, more generally, the gaps left in conversation between two people.

In modern life, we are always receiving images and are compelled to slot them into some kind of logic. Signs and symbols are imposed on us and, subject to that assault, we want to make sense of them. As the narrator puts it: “When I opened my eyes again a story was unspooling itself around me, a story that didn’t concern me and yet nonetheless stretched itself over my tired body.” Friends, strangers and the world are constantly telling us something, stretching meaning over our tired bodies. Someone sends a screenshot, another tells a story, another shares a link, another posts a photo. And with all of this content, we want to understand it, categorize it, control it. We want to make sense of the communication. Supplication sits in those gaps in communication, in the correspondence of meaning from one person to another. Is this a metaphor? Or is this just the story? Always, in the saturated (horror) world of contemporary life, we are required to ask: Are you trying to tell me something? Is this what you mean?

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra