In each edition of Xtra, a literary Canadian recommends a queer-authored book. In this installment, poet and Xtra editor Marcus McCann recommends Jane Rule’s The Young in One Another’s Arms (1977).

***

Family, thank God, isn’t only what you’re born into.

Gays and lesbians have been tracing out networks of friends and lovers for decades, tight-knit groups that love and support each other. We eat together, make house together and sometimes go to bed together.

In Jane Rule’s The Young in One Another’s Arms, a miscreant group of boarders gradually realize their mutual affection, growing, as the book progresses, into a kind of idealized chosen family.

Ruth, a one-armed war vet, is the den mother. She owns a rooming house, where she looks after the wounded young souls of Vancouver. She also looks after Clara, her mother-in-law. (Ruth’s husband, importantly, is absent through most of the book.)

But as the outside world presses in — especially the Vietnam War and ongoing police violence in Vancouver — the motley crew sails for Galiano Island (where Rule herself finished out her days). There, they make a home for themselves, open a café and raise — as a group — a baby recently born into their chosen family.

In his 1977 review of the book in The Body Politic (Xtra’s predecessor), Michael Lynch describes the book as “a gentle, serious comedy” that relies on stereotype and artifice. This is certainly true and a way to explain some of the book’s less-than-subtle character sketches.

Perhaps, more than 30 years later, parable might be the right word. The Young is a parable about family, rather than high-realist portrait. As Lynch says:

“Its importance lies rather in its tone, in the quality of its truth, when we set about to offer collective alternatives to exploitative family units. We need a language, a tone, which lets us be different by caring, to show anger without hate.”

So is this kind of chosen family possible?

Lynch’s point, I suppose, is that Rule’s world is a little utopian. Open-minded and open-hearted characters come together and, with relative ease, dispense with their baggage.

But take, for instance, this short passage about a straight guy (Stew), as he helps one of the boarders (Gladys) move out and is confronted with a gay Vietnam war resister (Boy).

“Stew had [no] difficulty with Boy, even took his flirtatiousness without archness or alarm. Whatever else Gladdy did to the men whose beds she had shared, she gave them a liberal confidence about what it was to be attractive.”

I can’t help but think, “I’ve met people like that.”

But then the utopian creeps back in, and I think, “I want to be like that” — like Stew, easygoing; like Boy, uninhibited; and most of all like Gladys, lending confidence to my lovers.

Naturally, the move from observation to yearning happens as much in the reader’s mind as it does on the pages. And there, exactly, lies the promise of the novel.

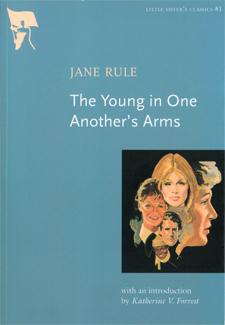

When Little Sister’s bookstore joined with Arsenal Pulp Press to begin reissuing gay and lesbian classics in 2005, The Young in One Another’s Arms was the first in the series. It’s a handsome reissue, with some extra material (an essay, early reviews, a reproduction of a bit of the manuscript) helping to beef up this slender novel. It’s an excellent way to enjoy the book.

Marcus McCann is the managing editor of Xtra. His first collection of poems is Soft Where.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra