Colm Tóibín has the brows of a boxer and the eyes of a poet. His fingers flex the air when he talks, like sensors searching for meaning, and his face often fills with wonder at the sheer, intriguing oddity of the world.

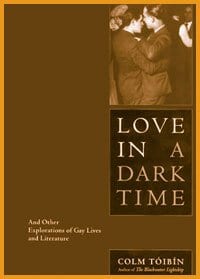

He was in Toronto to promote his latest book, Love In A Dark Time, a collection of literary essays on gay writers and artists, many of whom were not known as gay during their lifetimes.

Well-known for two gay novels, The Story Of The Night and The Blackwater Lightship, Tóibín [pronounced toe-bean] wasn’t always so comfortable with his sexuality. By the early 1990s, he had written two novels, much journalism and several non-fiction works, and had just started the mesmerizingly melancholy The Story Of The Night, when an editor at the London Review Of Books asked him to write about being gay. Shocked, he declined. “I don’t have any even sort of private version of that [the gay issue] that works even for me,” he told the editor.

Like many gay men, he had compartmentalized his life, leading one life in London, another in Ireland and a third still in his home town of Enniscorthy, on the southeast coast of Ireland, where he was “just a nice boy who wrote nice novels.”

But he started writing about gay artists for the Review and gradually his own path became clear. Some of the early pieces on Elizabeth Bishop and Thomas Mann were written to deadline. But some of the later, and quite impassioned pieces, on Oscar Wilde, Francis Bacon and James Baldwin, were written with a book in mind. “The book in some ways enacts my own coming out, my own making myself much more clear,” says Tóibín.

Composed of equal parts criticism and biography, the essays proceed at a gallop. And Tóibín is invariably insightful, even when treading such well-travelled ground as the life of painter Francis Bacon.

Bacon’s second major lover, George Dyer, died in 1971, possibly a suicide, and biographers love to paint him as an “embarrassment,” says Tóibín. But Bacon clearly loved him and the evidence is everywhere to be seen in the paintings, even the images of Dyer dead on a toilet in a Paris hotel room. If straights think otherwise, it’s because they’re following a script. “Queers are alarming, which means their relationships have to be shrill,” says Tóibín.

Despite his insights, Tóibín is ambivalent about exploring artists’ lives, thinking it can get in the way of the work. In one of the most touching essays in the collection, a piece on prominent American poet Elizabeth Bishop, Tóibín remarks with trepidation that, “her life is likely to rival that of Sylvia Plath as a subject of infinite fascination.”

Bishop had several intense lesbian relationships, including one with a Brazilian woman set against the exotic backdrop of Rio de Janeiro, but the details of her life weren’t known until after her death in 1979, and the subsequent publication of a biography and her letters. The poems, on the other hand, were important to Tóibín long before he or the world knew Bishop was lesbian, back when he was a young and very naïve gay man leaving Ireland for London and post-Franco Barcelona, and he doesn’t want to lose that magic.

But he’d also like to know at least as much about gay history as he knows about Irish history, which is a lot. The problem, of course, is that “gay history is a dotted line… into the past… that becomes very faint and disappears. So when we have a direct hit, as it were, in a life, such as Mann’s or Bishop’s, a closeted life but nonetheless a gay life, we have to take enormous interest in the life, even though by doing so it takes away from the autonomy, beauty and importance of the work.”

Artists are important insofar as they leave a documentary record of their lives. They “tend to carry the brunt, in a way, of the dotted line of gay history. It’s easier to write about Oscar Wilde than it is about his next door neighbour, who may have been up to exactly the same things at the same time but just didn’t get caught.”

And is there a gay sensibility, something that transcends a simple choice of partners? Well, yes, says Tóibín, though it’s hard to put it into words and if you push the idea too hard it will simply disappear.

As a young gay man in the 1970s Tóibín was drawn to certain books before he knew their authors – Mann, Baldwin, Thom Gunn and Bishop – were gay. There was something in the tone, “Something silent, secret, hidden.”

Bishop’s “impersonal and melancholy” work may have been more influenced by her being an orphan and by her being from England than by her being lesbian. “But you can never tell the extent to which being gay doesn’t instill itself into every area of your being in strange secret ways that we can never fully understand.”

Tóibín’s next book is a novel about one of the most repressed homos of all time, Henry James. James’s work seldom even hints at homosexuality (“It is astonishing how James managed to withhold his homosexuality from his work,” writes Tóibín) and it’s uncertain whether James ever had a physical homosexual relationship, though one youthful liaison may have involved the future supreme court justice Oliver Wendell Holmes.

Tóibín’s fictional novelist isn’t much better at love, says Tóibín. “He’s much better at withholding and not doing it and watching it and contemplating it and then going home. But it’s all there.”

For a man like James whose most famous line is, “Live all you can; it’s a mistake not to,” this could be construed as a tragedy. For a novelist like Tóibín, who’s interested in the dramatic possibilities of denial, it should be a gold mine.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra