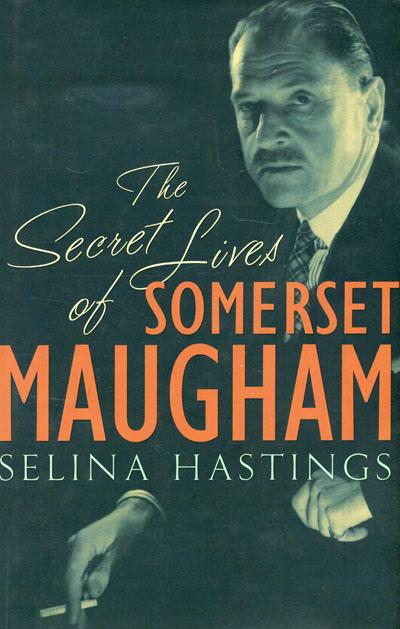

During his lifetime, playwright and novelist Somerset Maugham meticulously burned or otherwise covered up evidence of his love for men. Selina Hastings attempts to fill in those historical blanks with her new book, The Secret Lives of Somerset Maugham: A Biography.

At 549-pages, Hastings’ book is formidable but fascinating. The author reconstructs Maugham’s queer life with gossipy anecdotes about man-to-man affairs. She employs the trappings of fiction to set pace and tension. The approach makes the book into more of a page-turner, but the author includes platitudes and insights that seem, at times, overly speculative.

That aside, Maugham is undeniably fascinating. One of the most famous English-speaking writers of the first half of the 20th century, he was prolific. His work includes the novels Of Human Bondage and The Razor’s Edge, as well as dozens of plays and hundreds of short stories. A literary rock star of his era, Maugham eschewed the bohemian lifestyle, preferring the finer things in life, including his luxurious home at the Villa Mauresque. That’s where Maugham kept his gay life completely separate from his gentlemanly life, or so he thought.

Though already sexually active with men, in 1917 he entered into what would turn into a disastrously unhappy marriage to Syrie Wellcome, who was pregnant. They divorced a decade later, at least partly because of Maugham’s long-time relationship with his much younger assistant, Gerald Haxton. The two were lovers until Haxton’s death in 1944.

But the love that dare not speak its name hardly whispered in Maugham’s attacks on social morals. According to Hastings and Gore Vidal, Maugham’s two “crypto fag” novels – stories with encoded gay experiences – are The Narrow Corner and Christmas Holiday. Corner features a seemingly obvious queer relationship between a doctor and his servant. Holiday’s handsome protagonist, Charlie, visits Simon, his best friend from his boyhood. Simon, estranged and living in Paris, is enamoured with Charlie.

Critics often considered Maugham populous and middle-brow. Maugham was widely read and honest about his literary acumen. He admitted to lacking inventiveness, requiring real life as fodder for his fiction.

Certainly Maugham was respected and, outwardly, a gentleman. However, he does not appear to have been especially well-liked personally. In his decline, he fought with his daughter over his estate and published, against better judgment, a thinly disguised indictment of his marriage. Both acts antagonized whatever friends he had left. Disappointingly, Hastings takes sides in both cases.

Hastings has dug up many stories, allowing readers to become just enough acquainted with Maugham to feel uneasy.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra