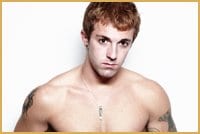

“Poets aren’t supposed to have such nice arms,” said an attendee at the recent Vancouver launch of Seminal: the Anthology of Canada’s Gay Male Poets.

The tattooed and muscular arms in question belonged to Sean Horlor, the anthology’s youngest contributor and the author of Made Beautiful by Use, a poetry collection that explores everything from the homoeroticism of Catholic Saints to poems comprised and twisted entirely from George W Bush’s speeches. (Who knew that George W’s words could describe party culture and fitness regimes so nicely?)

I first met Horlor at a poetry reading that I emceed in Victoria back in 2003. Although I recall some of the poems and chitchat, what I remember most about that evening is the direct correlation between the age of the poet and the amount of clothes they wore. While some of the more mature women wore elaborate shawls and scarves, the young female poet wore a bra on top and the young male poet wore his shirt completely unbuttoned. That young poet was named Sean Horlor.

Apart from the Skank literary smut cabarets I used to help produce which featured strippers and performance artists, Horlor’s nipple was the first—and the last—I’ve seen at a literary reading.

When asked what he believes poets are supposed to look like, Horlor concedes that Vancouver’s West Coast sensibilities have probably influenced people’s perceptions, so that when they see a poet without a black turtleneck and thick black glasses, not to mention bongos or empty liquor bottles, they get confused.

He goes on to describe how he often gets mistaken as straight and that when people find out that he’s gay, let alone a gay poet, it sometimes takes them a few moments to process the information.

That said, if people end up reading his poems because they like his arms, or eyes, or whatever body part, he believes it’s a small tradeoff if it means people take the time to read his work.

That this gay poet also used to work for Premier Gordon Campbell as a speech writer; or that he used to work at Butchart Gardens and can name all the flowers and plants as he walks down a street; or that he runs half-marathons; or that after partying all night he’d hang out in his tight t-shirt with 80-year-old nuns in Victoria to talk about the lives of Saints—”I came for books, but stayed for the sister-to-sister chats,” he says; or the fact that much of this interview took place around the ping-pong table in Horlor’s living room can only complicate people’s perceptions. (For the record, Horlor is a much better writer than ping-pong player.)

“I think there’s sort of a definite expectation for gays to be smarter, be cleverer, be wittier, to be more things to more people,” he says. “Most of the time I feel like an actor. How much can I get away with?”

While Horlor’s poetry avoids the overt, confessional nature of many of his contemporaries, his life experiences inevitably sprinkle and infuse his words. Although he doesn’t write an obligatory “coming out poem” or “my first rave poem” many queer readers will pick up on the subtleties of his gay sensibility.

His is definitely a collection by someone who has held a glowstick in his hand. And definitely a collection from someone with Catholic roots.

“I grew up thinking that it was important that you believe in something, not necessarily a god, but something,” he says. “It’s been a pleasant surprise to me just how many gay readers have connected to my section of the seven heavenly virtues. I find that intriguing and refreshing.”

Many writers have remarked on the meditative and observational nature of his poems, a quality rarely seen in someone so young—especially someone born in the ’80s, a decade better known to some for its shoulder-pads-influenced women’s fashions. In 2006, his poem “In Praise of Beauty” won This Magazine’s coveted Great Canadian Literary Hunt Award. He’s also received Canada Council grants and scholarships to the Banff Centre.

“There’s a gay poet and a poet who is gay,” says Horlor. “They don’t necessarily have to be exclusive, but there are those two terms. I had to mature personally in order to feel comfortable to write gay themes and realize that I belong to a long gay tradition. I’m proud of the fact that I can walk down the street holding hands with my boyfriend and it’s because of the hard work of those people 10, 20, 50 years ago. To pretend not to be a gay writer is a slap in the face of those people.”

On his inclusion in the groundbreaking anthology of Canadian gay male poets, Horlor reflects on his years of feeling isolated in the writing department at the University of Victoria, where he was the only male poet, let alone gay one. “I would have loved to have had access to such a book and all its poets. Sometimes I felt like such a unicorn. I hope my work, along with the other contributors, inspires a new generation of poets.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra