It’s a terrifying reality many independent theatre directors have had to face: an actor gets sick and drops out of the show. While the situation usually leads to a fevered process of recasting to get things back on track, Natalie Feheregyhazi used just such circumstances as an opportunity to take a different approach with her production of Michel Tremblay’s La Duchesse de Langeais.

Penned in 1973, the piece calls for a single male actor to play an aging lovelorn drag queen. But rather than search out another guy to fill the role, Feheregyhazi adapted the piece to be performed by trio of actors: two men and a woman.

“There were so many themes in the play I related to as a woman that I thought it would be interesting to explore the text through a female voice,” the Saskatchewan-born, Paris-educated director says.

“I’m the kind of woman who never wants to show vulnerability publicly, even though I have a very sensitive nature, which is exactly what the character in this piece is experiencing. We have a tendency to brush off loud, brassy women, but I want people to think about the fact that underneath all that there’s often a huge sensitive heart.”

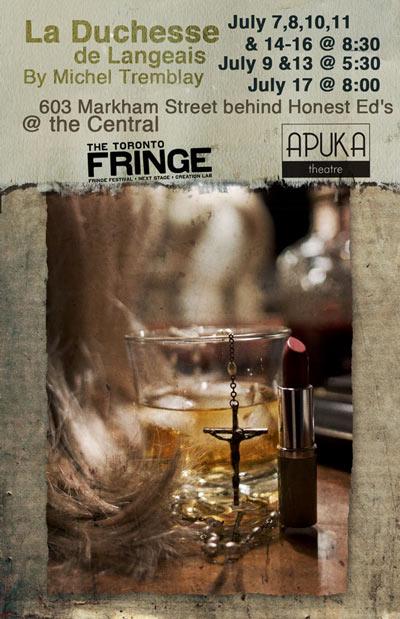

In the original piece, La Duchesse drowns her sorrows in cheap Scotch while speaking about a doomed affair she’s recently had with a handsome young man on a tropical vacation. Long past her prime, she gradually comes to the realization that she no longer has the sexual currency she once did and berates herself for thinking the object of her affections would enter a lasting relationship with her.

“I’ve spoken to a lot of men in that age bracket about the experiences of the character, and they all say she’s made an obvious mistake and should know better,” Feheregyhazi says. “But the desperate need to be loved and nurtured hasn’t faded with age, and she’s struggling to find it. Losing one’s value in society as their physical attractiveness fades is another element a lot of women can identify with.”

Splitting the role into three parts also suggests the Holy Trinity of the Roman Catholic Church, a nod to the intense religiosity that permeated French Canada in those years. Both Tremblay’s own life and the lives of many of his characters were marked by a schism between being true to their identities and sexuality, while living in terror of eternal hellfire for going against the laws of the church.

“The character grew up in the first half of the 20th century, so the church was still a dominating force in daily life,” Feheregyhazi says. “Her internal dilemma of living a life that is true to who she is, but fearing that the sin of being gay will lead to damnation, is a huge part of her experience. She’s at an age where she can see her own death on the horizon. She’s torn between living the life she wants and being redeemed before death.”

In addition to the unconventional casting, Feheregyhazi has adapted the piece to be presented in a bar. Abandoning the comfortably controlled environment of a theatre for the unpredictability of a local watering hole has its challenges. But Feheregyhazi saw it as an ideal setting for a few reasons.

“I’m primarily interested in the connection between the characters and the audience, and working in a site-specific venue allows you to do that in a more effective way,” she says. “I worked as a bartender for years, and so I’ve seen many manifestations of this character, inviting people to join in their drinking as a means of connecting with them so they can tell their story. It seemed like a perfect way to present the piece.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra