When Rachel Pollack was 15 years old, she experienced a miracle. She had been diagnosed with cancer that year, and her parents, who were conservative Jews, made a vow to remain fully kosher for the rest of their lives if their daughter survived.

“Her parents brought her in to have surgery, ” her widow, Zoe Matoff, tells me over the phone. “They opened Rachel up, and they found that it wasn’t cancer. It was extreme calcium deposits. And they actually took a hammer and chisel and hacked away at Rachel for four hours.”

Pollack lived. For the rest of her long life, she believed that she’d had cancer, and that it had been transformed by her parents’ prayer.

Matoff has seen plenty of miracles since Pollack died at age 77 on April 7 of this year: showers of golden leaves on her grave in midsummer, a floral scent in her bedroom that never goes away. Matoff still uses present tense when speaking of her: “I say is because, you know, she’s around, my God. I’m getting reports about it. She’s helping people. They’re writing every day to me, telling me ‘Rachel’s helping me,’ you know? Like, she sits on the edge of their bed and they have a discussion with her.”

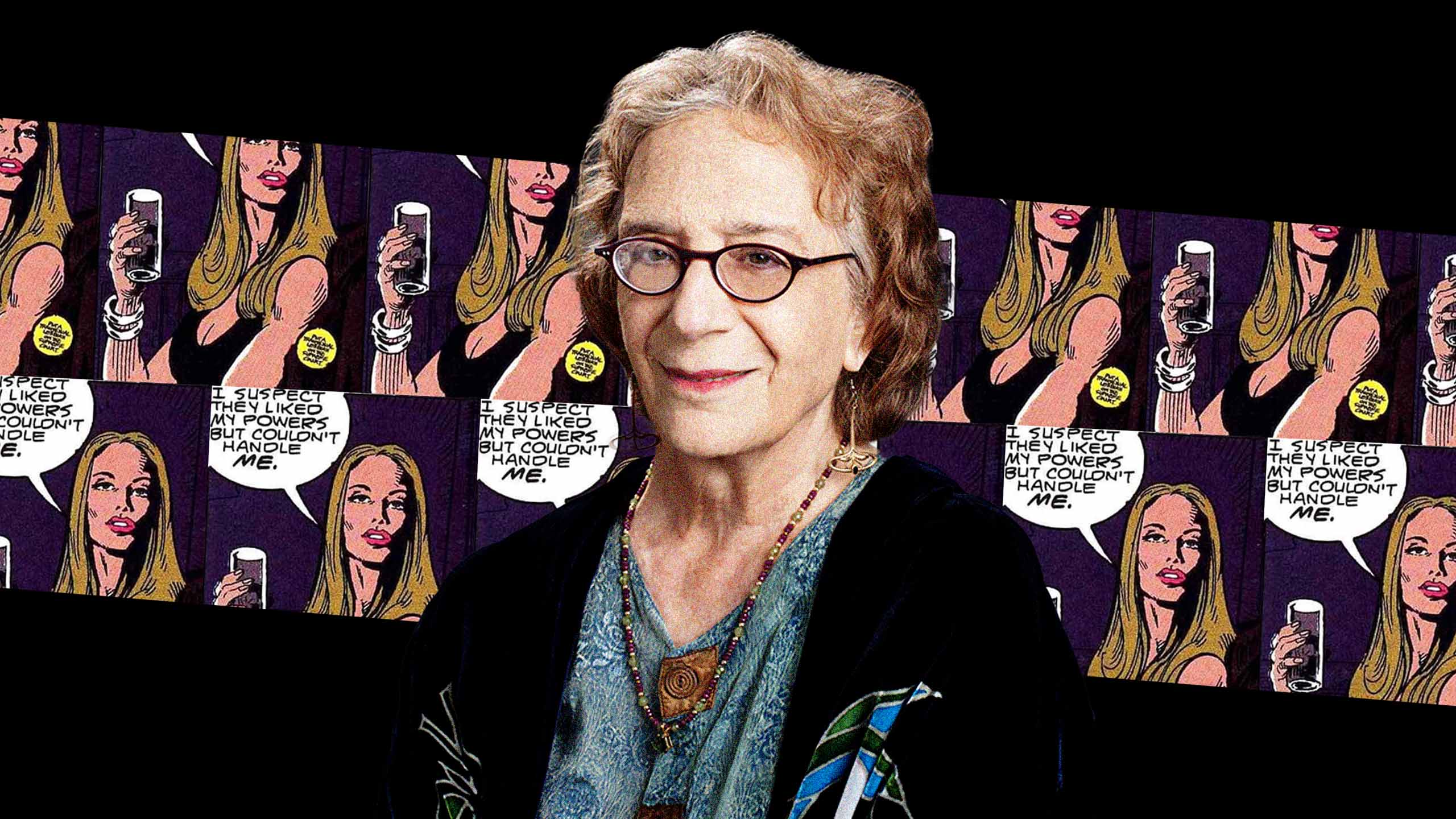

Pollack saw miracles in the world, and she was someone who taught other people to see them. Most famously, she did this through the Tarot; she was a world-renowned expert on the cards, consulted and cited by authors like Alexander Chee and Neil Gaiman. Her book on the Rider-Waite, 78 Degrees of Wisdom, is the go-to text for anyone trying to learn the cards. Yet the number and diversity of Pollack’s accomplishments make it hard to sum her up: She was an activist. She was an award-winning science fiction novelist. She was a comic book writer, who created what is widely cited as the world’s first trans superheroine, Coagula, for DC Comics’ Doom Patrol.

I first became interested in Pollack’s life because of one line in her (surprisingly short) author bio: “She was a great influence on the women’s spirituality movement.” It’s a line that can be read two ways: either she was a very big influence, or she was a very good influence, and the latter was sorely needed. Pollack was a trans woman—an out and politically active trans woman, at that—and “women’s spirituality” was one of the most infamously transphobic corners of feminism’s second wave.

Here is another miracle in the story of Rachel Pollack: as early as the 1970s and 1980s, in the midst of a TERF stronghold, a transfeminist lesbian was trying to create a trans-inclusive vision of spirituality. Not only was she not kicked out, but she actually won.

Rachel Pollack was born in Brooklyn in 1945 and raised in Poughkeepsie, New York, but she often said that her life began in 1971: the year she sold her first short story, came out and discovered the Tarot. She had been thinking about her gender for a long while, until—in the middle of an acid trip—she realized that her greatest fear was that she actually wanted to be a woman. The instant she realized this, she said in a 2021 talk to Arts University Plymouth, she also knew that she already was a woman, and always had been. From there, it was just a matter of telling the world.

The early years of Pollack’s transition were spent in London, England. Her coming out coincided with the birth of the gay liberation movement in the U.S., and for that reason, going stealth or assimilating into the cis world was never something she wanted. She was visible and political from the beginning: in 1972, she helped to write the trans manifesto “Don’t Call Me Mister You Fucking Beast,” along with poet Roz Kaveney and several others. In the 1990s, she was a regular contributor to TransSisters: The Journal of Transsexual Feminism.

Pollack was also tight with the cis lesbian feminist community in London, until, suddenly, she wasn’t anymore. In her telling, she was blindsided: early in 1972, she left England with her then wife, Edith Katz, to visit family back in the U.S., and came back a few months later to find that trans women were no longer welcome in the movement.

“I had lots of good friends, or so it seemed,” Pollack said, in a 1995 interview with TransSisters. “When we left, there was a going-away party for us by this group of radical women who had a commune; and they were crying and saying, ‘We’re so sorry to see you go. Please come back.’ We went away, and three months later we came back, and the very first thing we did was to rush to see our good friends. There was one particularly good friend of ours whose name was Frankie. When we rang the bell, another woman answered the door and she stared at us and she said, ‘Frankie’s not here. You can wait in there,’ and she pointed to a room in the back. We went into that room, and it was empty—there was no furniture in it—and we were kept there like we were penned.”

Pollack and Katz were eventually rescued, but from that point forward, the treatment Pollack received from cis feminists was so hostile that she moved to Amsterdam to escape it. She was grateful the change was so sudden, she told TransSisters, because it made it impossible to blame herself: “I would have been tempted to think, ‘Well, I must have done something. It must be my fault, I must have acted badly.’ Instead, for me it was an overnight shift.”

This may explain one of Pollack’s most distinctive qualities, one that was mentioned by nearly everyone I interviewed for this piece: she faced tremendous amounts of bigotry and hostility without ever seeming to internalize it or even acknowledge it. Matoff tells me that when she and Pollack walked down the street, people would turn and stare. Matoff would want to fight them, and Pollack would calmly wave it off. She seems to have felt that other people’s transphobia was neither her fault nor her business.

“She never took anything personally. She just knew who she was, and she didn’t let those things touch her. It’s amazing,” Matoff says.

This approach extended to how she dealt with other feminists. “Some of those early feminists were militant, [and] still are, about who could be a feminist and who is whatever gender they are,” says Pollack’s student Janet Maika’i Rudolph, who runs the blog Feminism and Religion. “In my experience, at least, she sidestepped all of that and just went this whole different direction.”

When her friend Neil Gaiman created the trans character Wanda Mann for The Sandman, he showed Pollack what he’d written. Gaiman says she wasn’t pleased—and, certainly, Wanda has come in for her fair share of criticism from trans people over the years, with Gaiman himself admitting he’d write her differently today. There was no falling out, however: “She felt I’d got [it] wrong, so told me she would remedy that by putting her own trans character, Coagula, into Doom Patrol,” Gaiman wrote on Tumblr earlier this year.

The first trans superheroine in comics came into existence because Rachel Pollack wasn’t happy with how other comic writers were portraying trans women. Over and over, rather than fighting bigotry or internalizing it, Pollack sat down to out-create it. Coagula was neither her last such project, nor her most ambitious. Within a few years, Pollack would go from inventing heroines to creating gods.

The women’s spirituality movement evolved out of the second wave of feminism, in response to the recognition that the Christian church (among others) was a preserve of the patriarchy. The way we imagine God tells us what we value, these feminists argued: Western Christian patriarchy’s insistence on a God who was bodiless, asexual, supernatural and male reflected a world where the body, sexuality, nature and women were subjugated.

Women’s spirituality aimed to replace those patriarchal myths with better ones. What that meant was, very often, imagining God as female, and uncovering stories of powerful Goddesses in ancient myths. The problem is that imagining God as a woman tends to summon up a specific mental image of “woman.” Here is where the shit really hit the fan.

Childbirth, pregnancy and menstruation were venerated as the central features of the Divine Feminine. Vaginal iconography was everywhere. The “sacred womb” of the Goddess was invoked at rituals. Goddess worship had two main strains: Lesbian separatist groups, which outright forbade trans women to participate, or Wicca, which was slightly more open, but taught that the life cycle centred on procreative sex between a female Goddess and a male God. (That God, by the way, tended to be defined as much by thrusting rods and staffs and stag antlers as the Goddess had ever been by her uterus.)

Tamsin Davis-Langley, who writes on queer spirituality under the name Misha Magdalene, entered the pagan community in the mid-1980s, before she knew that she was trans.

“I came into witchcraft and paganism and Goddess spirituality expecting things to be really inclusive and welcoming and open, and they were in some ways. And then I started finding all of the places where they weren’t,” she tells me. Even before her egg cracked, the transphobia hurt: “It was difficult for me because I was in my teens and then my twenties as a girl who didn’t know she was a girl. And I was like, all of these things speak to me, but I am not welcome in the places where they are being spoken.”

Many of the “feminist” tarot decks of the ‘80s and ‘90s were born from this culture. You can get a taste by reading the guide to Vicki Noble’s popular Motherpeace deck, published in 1981: The Emperor card, which traditionally represents worldly authority, here represents rape, male violence, “an angry patriarchal structure” and “authority, maybe your boss or your father.” Meanwhile, the Hierophant, representative of organized religion, “has taken over the robes and skirts of the High Priestess, along with the breasts, which symbolize her sacred power,” thus portraying the forces of Christian patriarchal domination as an AMAB person in a dress. The only positive male figures in Noble’s deck are the Sons, who replace the traditional Knights—children, subordinate to their mothers, and thus safe.

Here, from Pollack’s self-designed deck the Shining Tribe, is her description of the Emperor: “A number of modern tarot decks have taken on the issue of patriarchal culture. They have tended to see the Emperor as a kind of villain, with gentle, childlike males as an alternative. Such images both belittle men and demonize them.” Instead, Pollack offered, women who drew the Emperor card might try to see themselves in it: “It might be a strong experience to imagine ourselves as the Emperor. What might it be like to contain and express such power and determination?”

The Hierophant is changed to the gender-neutral “Tradition,” and that is that. It seems to be as close as Pollack ever got to a direct rebuke of her peers’ transmisogyny. Yet that tiny tweak—don’t look for male power, look for your power—changes everything about how people see these cards, and therefore, how they think about gender and power when reading them.

Your tolerance for woo-woo may vary (though, if it really bothers you, I would suggest not reading an article about a tarot expert) and it’s true that contemporary feminists often dismiss women’s spirituality as a relic or a theoretical cul-de-sac. Yet it did have an impact on the wider culture: in Gaiman’s Sandman, for instance, Wanda is harshly rejected by the moon Goddess because she doesn’t menstruate. It’s not portrayed positively (we readers like Wanda a lot more than we like the Goddess), but it’s a pop-culture rendition of what most people took to be the default feminist stance at the time.

Pollack believed the Goddess would accept Wanda. Soon, she set out to prove it. Her biggest contribution to women’s spirituality, The Body of the Goddess, was published in 1997. For a trans woman to write a book on Goddess worship in the mid-’90s was gutsy. For a trans woman to call that book The Body of the Goddess is fucking bonkers. It’s mind-blowing. It gets more so when you open the book and find that Pollack’s Goddess not only likes trans women; she is one herself.

Pollack doesn’t ignore menstruation or childbirth as aspects of female embodiment, but she doesn’t stop there either. She also locates trans and gender-fluid goddesses throughout mythology. Some—like the intersex goddess Cybele and her likely transfeminine priestesses, the Galli—are canonical. Others are creative interpretations of existing myth: Pollack notes that the Greek goddess of love, Aphrodite, is “created” when a male God named Ouranos loses his genitalia. Afterward, Ouranos essentially disappears, and a brand-new, very feminine Goddess arises to replace him.

Even trans guys get a turn. Pollack tells us that Dionysus, the Greek god of wine, madness and ecstasy, was raised as a girl and was sometimes known as “the Womanly One” for his feminine looks and unusual kindness to women. In a 1995 essay for TransSisters, she gets even more detailed: Dionysus “went mad in adolescence,” was cured by Cybele, and went on to become an androgynous he/him whose myths portrayed him liberating people of all genders from the patriarchy. At rituals, Pollack tells us, “his male followers would dress as women, [and] his female followers would strap on large phalluses,” suggesting that liberation took a highly recognizable form.

“Back in my time, because it was so early, everyone was defined as sick, being trans was a sickness,” Pollack said in a 2021 interview with LGBT+ Health and Wellbeing of Scotland. “I started seeing that the alternative—the way not to be sick, is not to say I’m not sick, I’m okay. Because that’s negative … The way to overcome sickness is to have power, to see that what you’re doing is a great thing. And that it’s worldwide, and as old as humanity.” It was important to find images of trans divinity, she told TransSisters, because “the way for us to have a healthy sense of our bodies is to see ourselves mirrored in a context that’s not a medical context, in a context that a more beautiful, deeper, profound aspect to it, and in this case, it’s a religious context, or a sacred context.”

It matters for a trans woman to see her body as the body of the Goddess, just as it mattered for many cis women to envision a God who could menstruate. Finding Dionysus in the Greek pantheon feels like finding Pollack in the women’s spirituality movement, or Pauli Murray behind Ruth Bader Ginsberg, or Sandy Stone at Olivia Records. It’s proof that not only have trans people always been part of the story, but some of the most famous stories in the world are about us. In those stories, we are not dirty, or shameful or victimized. In some of those stories—like Rachel Pollack’s story—we are divine.

In the 2020s, the women’s spirituality movement is rapidly fading from memory. Some leaders, like the feminist and environmentalist Starhawk, have spoken out in support of trans rights. Others, like Z. Budapest, are still spreading conspiracy theories about trans women and hexing people who try to update their chants.

In terms of legacy and impact, Rachel Pollack towers over nearly all of them. She is possibly the most well-known tarot writer of the 20th century; 78 Degrees of Wisdom is still bought with many people’s first decks by default. She has only become more influential as time passes: Tarot is increasingly mainstream, and U.S. Games Systems editor Lynn Araujo estimates that tarot deck sales “have doubled or tripled every year for the past ten years.” That’s a lot of first decks, and a lot of people reading Rachel Pollack; many of whom don’t even know she’s trans.

Rachel Pollack was not a fortune teller, but she did successfully predict the future: in 2023, “alternative spirituality” looks a lot more like her work than it does like the second wave. There are now dozens of queer and trans tarot decks, from artists like Fyodor Pavlov and Trung-Le Nguyen. adrienne maree brown, author of Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Changing Worlds and Pleasure Activism: The Politics of Feeling Good, has co-designed a tarot deck; novelist Michelle Tea has written a tarot guide and hosts a podcast on magic and spirituality. There are whole stores devoted to queer Tarot and an entire industry of experts who translate Tarot, astrology and other occult topics through a queer lens: The astrologer Chani Nicholas has around one million subscribers to her smartphone app. Meanwhile, unless you belong to an incredibly specific subculture, you probably don’t know who Z. Budapest or Vicki Noble are.

Pollack was aware of the queer Tarot renaissance, and she was excited about it. Cassandra Snow, author of Queering the Tarot, says Pollack was endlessly supportive and generous of younger writers. “My work has gotten a lot of resistance in being too modern or DIY, even by other queer folks in the tarot community, but Pollack was never one of them. She was enthusiastic and excited to see what others had to say, and I think that kind of encouragement and enthusiasm did even more to open doors,” Snow told me in an email.

That, too, is something mentioned by nearly everyone I spoke to. “You know, it’s like almost everybody and anybody would say that about her,” says Rudolph, her former student. “She just really encouraged people to follow their creativity. She was always, not only supporting, but pushing for more thought.”

She got it. Pollack’s is that rarest of stories: a total trans win. Pollack did not stop with asking for “inclusion” or “acceptance” in a cis-dominated and transphobic community. She transformed that community, re-created it in her own image and emerged as a leader—and, what’s more, she lived long enough to see her victory. It’s a fitting outcome for a woman whose faith in herself was almost crazily unshakable: “She’s optimistic as all get-out,” Matoff tells me, “to the point of what? Are you in denial? How can you be so optimistic about this? But, you know, she would turn out to be right.”

Toward the end of her life, Pollack was working on her memoir. She had actually completed the manuscript—written, like all of her books, by hand in a notebook—and was in the process of dictating it to Matoff and two other people (Matoff can’t tell me who; she says they’ve been sworn to secrecy) when she passed. She was excited about how the book was shaping up. “She would go to the library every day or some spot in the village, and she’d come home and I’d ask her, did you write your memoir?” Matoff says. “She said, ‘Yes, I did. It’s so exciting. I’m remembering things I haven’t thought about for decades. It’s so good. It’s so good.’”

Matoff now believes the book will never be published. Pollack did not just write her books by hand—she wrote in a shorthand of her own creation, which no one else can decode, and her handwriting was exceptionally sloppy. “You can’t read what letters she’s written,” Matoff says. “So even though she says she finished her memoir, and it’s all written down, no one can read it. She was reading her written manuscript [to us] so we could type it up so that it could go forward in publication. But she never finished.”

Rachel Pollack, the great interpreter of symbols, left us her final book—her life story—in a code no one can decipher. It’s all there, but it’s waiting for someone to figure out what it means. Delivering her whole story to the world would take a miracle. When it comes to Pollack, miracles are not in short supply.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra