ROYAL TREATMENT. The Royal is unveiling a major retrospective of Bruce LaBruce's films including a limited run of Otto, a master class and a panel on censorship.

This year has been busy for iconic radical queer auteur Bruce LaBruce. The Toronto writer, artist and filmmaker premiered his new film Otto; or, Up with Dead People back in January at the Sundance Film Festival and has toured the world with it since, from Turkey to Brazil and all stops in between. As the year winds down the Royal is unveiling a major retrospective of his films including a limited run of Otto, a master class and a panel on censorship — a subject that LaBruce is keenly aware of. (Curiously his most controversial film, Skin Flick, will not be shown — a decision LaBruce wasn’t involved in.)

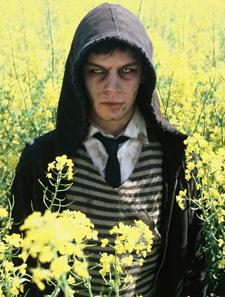

Otto, LaBruce’s sixth feature film in a career spanning two decades, is arguably his most mature work, a descriptor that will no doubt turn off some fans. Toning down some of his shock tactics — wound-fucking and roadkill-devouring scenes notwithstanding — and his more outrageous humour, Otto is a sweet, strange film about a hoodied lost boy who may or may not be a zombie.

Otto is also the perfect movie to launch a retrospective with, considering that it looks back toward youth while reworking key elements of LaBruce’s prior endeavours. “Otto is a summing-up film for me,” says LaBruce. “It kind of takes narrative ideas or fixations or thematic obsessions from my previous films and rolls them all together.

“I want to move in a different direction after this.”

The film is recounted by two very different narrators. The first is underground filmmaker Medea Yarn (Katharina Klewinghaus) who is in the middle of making her zombie agit-prop “magnum corpus” called Up with Dead People, which advances the idea that zombies are a “revolution against reality.” She tells us that what we are watching is taking place in the future, when zombies are common and capable of reason and speech. She also claims that the latest generation of zombies is gay, which has only increased the intense violence inflicted on them by the living.

The other narrator is a young man named Otto (Jey Crisfar) who believes himself to be a zombie and very well could be. Either way he is suffering from amnesia, with his former life coming back to him only in bits and pieces. As he staggers about Berlin, he encounters various misadventures as he pieces together his true origins, including falling in with Medea and her cast and crew, becoming Medea’s latest star.

LaBruce takes a totally unspectacular approach to his subject by suggesting that humans have become so zombified in our “somnambulistic conformist behaviour” that live humans never actually clue in that Otto is undead. (His rigid passivity brings to mind gay icon Joe Dallesandro, who was the dense rock around which the others’ dynamic personalities orbit in Paul Morrissey’s films.)

With its focus on an underground filmmaker, Otto brings to mind my personal LaBruce favourite 1994’s Super 8 1⁄2 (LaBruce describes Otto as “really a kind of remake” of this earlier film). LaBruce has a background in film studies and his critical take on film history, both mainstream and underground, and on their narrative, style and genre conventions are evident throughout his work. Typical of his self-reflexive approach, LaBruce identifies with Medea — thankfully his films are better than hers — but he sees himself in the young zombie hero as well.

“Otto sort of represents how I felt when I was a gay teen dealing with a world that is very hostile toward homosexuals and being super-sensitive in a really harsh environment,” says LaBruce. “Medea is more how I feel now. She has a broader political critique that extends beyond the gay world, she makes sense of the world through her art, which makes her more empowered and in control of what she’s doing.”

The cultural landscape has shifted significantly over the course of LaBruce’s career, with the homocore scene that he helped spawn spreading internationally and helping to foment a global queer movement that rejects mainstream values, institutions and aesthetics. What was once underground has become its own sort of niche market, particularly in the infinitely permissible contemporary art scene where artists like Terence Koh, a LaBruce collaborator, make big bucks with transgressive queer aesthetics. LaBruce is now competing for attention with the generation of provocateurs whom he inspired.

LaBruce never shied away from sexually explicit material in his work, which many of the most edgy New Queer Cinema directors never ventured into. “It really got noticed because there wasn’t that much of it going on at that time,” he says. “I ran into censorship problems. It was regarded as maybe a resurgence of more daring material that had sort of disappeared since the late ’60s or early ’70s.”

Over the past decade LaBruce has worked a lot in gay porn, but you couldn’t really say that he’s found a home there. “It is still such a conventional scene so I’m not so convinced at this point about porn being a site of subversion or radicalism. It just seems to almost stay the same or get worse. In terms of the critique presented by Otto – where [porn] is this place that attracts dead and damaged souls – I always argue that that’s its function: It’s the place where you work out a lot of politically incorrect sexual fantasies.”

Otto is also marked by a pronounced soft side, but LaBruce doesn’t find it that much mushier than his past work. “I think that [emotional] side is almost always there, it’s certainly in No Skin Off My Ass and Super 8 1⁄2, maybe less so in some films. But even in Hustler White, there’s a sentimental aspect to not only the relationship between my character and the hustler but between the other hustlers searching for tenderness in an extremely brutal world.

“Sometimes I think people miss the romantic and tender aspect because of the more obvious kind of brutality of the landscape.”

Ever the outsider, LaBruce draws on many different scenes while impishly satirizing their customs. Similarly his movies hop from one subculture to another, whether it be Santa Monica Blvd rent boys and sex radicals in Hustler White, Nazi skinheads in Skin Flick or leftist would-be-terrorists in Raspberry Reich.

While his current work isn’t coming from the position of extreme marginalization that he experienced in late-’80s and early-’90s Toronto, it hasn’t become comfortable and complacent either. Largely working in Berlin now, he has most recently invaded the city’s experimental theatre scene. “Berlin theatre is light years ahead of most of North America, so in terms of what I was doing — which I thought was strange and out-there — people thought it was maybe a little conventional.”

With actress Susanne Sachsse (from Raspberry Reich and Otto) and her performance troupe Cheap Collective, LaBruce created a theatre piece called Cheap Blackie: The Nine Stages of Death and Dying of the Bourgeois Family. LaBruce describes it as referencing the films Whity, Teorema, Boom and Reflections in a Golden Eye: “They’re all films about some sort of outsider/hustler character who comes into the bourgeois family and fucks them up or fucks them literally or makes them have some sort of epiphany or crisis in their lives. So I just took dialogue from the four films and mashed them all together or put them to music… it was almost like a weird avant-garde cabaret type of thing.

“I find that kind of environment really makes me question my own limitations.”

Following the performance’s big success, his next project is to create a follow-up production in fall 2009. It would appear that LaBruce has found a place that, in challenging his sense of what’s radical, feels something like home.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra