Most of us can’t imagine the reality of living in a warzone. Things may not be perfect here in Canada, but the idea of existing day-to-day in a country torn by fighting, terrorism and poverty is simply beyond our ken. It’s all the more startling and more miraculous to discover a vibrant, vivacious LGBT artist blooming in Beirut, Lebanon.

Alexandre is a male belly dancer, and in the midst of Arabic machismo and religious intolerance he is a flamboyant symbol of queer liberation. He blends in well enough by daylight, clothed in T-shirt and shorts, long hair tied back in a fashionable man-bun as he cycles through the broken city.

But when night arrives, he is transformed.

The music is sinuous. Slinky. Exotic. The dancer cascading long ebony curls, hips undulating, legs bare under sheer fabric, belly peeking out from a flimsy sequined top. This Alexandre, this unabashed expression of a powerful, effeminate gay man, is scarcely recognizable as his daytime self.

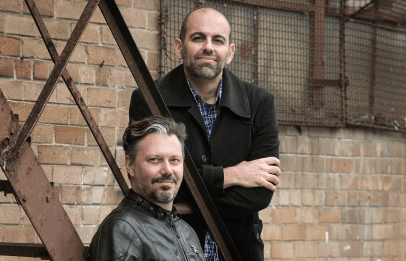

“When you see Alexandre you see an artist for change,” says Nabil Mehchi, co-creator and director of Interrupt This Program, a five-part documentary series for the CBC. Along with his partner and co-creator Frank Fiorito, Mehchi has visited cities reeling from major traumas in search of underground arts movements. The series’ premiere episode is set in Beirut, and showcases the efforts of a graffiti artist, a rapper and a writer. But Alexandre is the star of this show.

“Alexandre just walking on the street as a gay, effeminate man is a form of protest,” Mehchi says. “It’s a political statement. And in the Middle East, what he’s doing is revolutionary.”

Baladi, or belly-dancing, is an ancient art form normally relegated to women. It has waned with the rise of Islamic fundamentalism in the region, as women are not exactly encouraged to bare their tummies while gyrating on a stage. Alexandre aims to change that with his baladi stage show — even in the face of very real and present danger.

“My audience is essentially a very conservative one,” Alexandre says in the program. “But they are loving it because I’m a good dancer that dances something that they have missed. They have missed the authenticity of this art.”

When he first started out, Alexandre encountered resistance to the idea of a man dancing baladi. But that didn’t stop him from honing his craft, dancing at bars and pubs.

“What’s interesting is the reaction of the people,” says Alexandre. “The homophobes opening champagne, veiled women coming to sit at the table full of alcohol, very macho men asking me to dance. It’s interesting to see reactions of people that just needed to change their perception and their mood of the moment.”

Mehchi and Fiorito were inspired to create the series by their trips to Mehchi’s home country of Lebanon. He and his family escaped Beirut in the ’90s, as the bombing from invading Syrian forces inched closer and closer to their suburban home.

“We lived in a Christian enclave,” says Mehchi. “By the end of the ’80s there was a lot of shelling, and we lived in bomb shelters a lot. We had family living in Montreal, and Lebanon at the time was very francophone. So it was a good choice for us.”

Going back to his homeland has been both challenging and inspiring to Mehchi. On one hand it’s sad to see the devastation wrought by so many years of war, but the resilience of young artists is heartening.

“To be honest it’s very emotional to go back. You see a new generation that is much more empowered than we were. I feel incredible admiration, and I was humbled by them.”

Finding artists to profile wasn’t easy. There is no arts infrastructure to speak of in Beirut, and the only real network for creators and performers is social media.

“Facebook and Instagram play a big role,” Fiorito says. “We also talk to people in the field because, obviously, they’re not going to be in the newspaper.”

Both men found the underground culture a stark contrast to life in Canada. Fiorito was particularly shaken after witnessing the arrest of two men suspected of being gay.

“I feel privileged as a Canadian, being there,” he says. “Sometimes we complain of our country and it’s very trivial when you look at those people who have so much courage. That’s the biggest difference, really. Here artists don’t risk their lives to create their art.”

(Interrupt This Program premieres with Beirut: Art as a New Narrative

Friday, Nov 6, 2015, 8:30pm (9 NT)

CBC Television

The show will also be made available weekly to viewers online via cbc.ca/arts)

(photo courtesy of Martin Laprise)

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra