Kolkata, once the capital of British-ruled India, and today of the eastern Indian state of West Bengal, is the quintessential queer city. Dominique Lapierre’s “city of joy,” with its contrasts of affluence and poverty, perhaps starker than in any other Indian metropolis, shows all the signs of neoliberal globalization. Yet, it continues to embrace at least some shades of egalitarianism and left-wing politics, even as large parts of India turn decidedly right and intolerant.

At the time of India’s independence and partition in 1947, Kolkata witnessed gruesome communal violence. But autumnal Durga Puja festivities in Kolkata and West Bengal still reflect religious syncretism and fraternity that defy the polarization enveloping the country. Nearly 75 years into independence, Kolkata and Bengal haven’t exactly shaken off gender, class, caste and racial discrimination. But the legacies of 19th-century social reformists Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar and Raja Rammohun Roy seem to temper these shortcomings.

Home to names like writer and poet Rabindranath Tagore, filmmaker Satyajit Ray and economist Amartya Sen, Kolkata has been, or perhaps still is, a trendsetter. The city also had possibly the biggest queer icon in filmmaker Rituparno Ghosh (1963–2013). In a painfully short life, Ghosh won national accolades for nuanced depictions of human relationships, and acted and directed in some of India’s best queer cinematic efforts, for instance, Memories in March (2010) and Chitrangada: The Crowning Wish (2012).

“Each of them represents the Kolkata ethos of eclecticism, novelty and courage.”

Kolkata’s queer movements can also rightfully claim to have made an impact locally and nationally since the early 1990s. This was long before queer communities mobilized in many other parts of India. The city has had many firsts in the formation of support groups and coming out of queer-themed publications and cultural productions, and on July 2, 1999, Kolkata witnessed the Friendship Walk ’99, often billed as South Asia’s first rainbow Pride walk. It had just 15 participants, motivated equally by the 1969 Stonewall Riots of New York and Gandhi’s civil disobedience Salt March of 1930. A minuscule start 23 years ago has transformed into thousands marching in Prides in 25 to 30 cities across India.

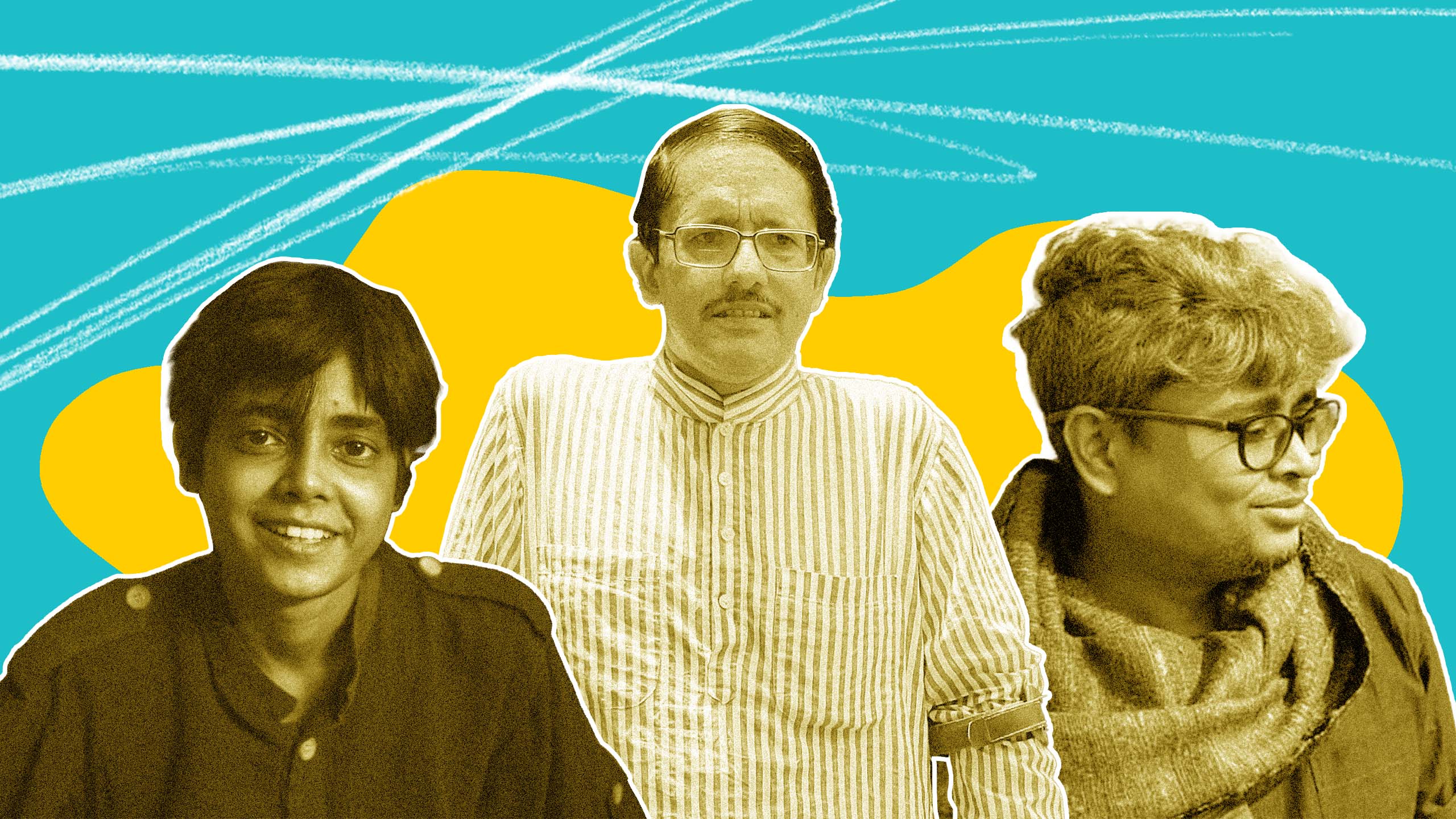

I’ve always lived in Kolkata, have co-founded some of the earliest queer initiatives in the city and in India, and continue to advocate for gender and sexuality diversity through a nonprofit called Varta Trust. I’ve known many queer writers, artists and artivists in Kolkata coming out with exemplary creations, but here I’ve selected just three. As India’s queer movements struggle to move beyond decriminalization (achieved through a landmark Supreme Court verdict in September 2018), these queer Kolkata artists seem to have something to offer for a dialogue on creating a less discriminatory social order. Each of them represents the Kolkata ethos of eclecticism, novelty and courage.

Debalina, 50, is arguably one of the most outspoken makers of queer-themed films in India. Her filmography has landmark and award-winning films in the context of India’s queer movements. There’s … ebang bewarish (… and the Unclaimed, 2013), based on the story of two women in a relationship who died by suicide in the village of Nandigram in West Bengal; and a fictional “sequel” to this film, based on the same event, called Abar Jodi Ichha Karo (If You Dare Desire, 2017). But she created buzz most recently with Gay India Matrimony (2019), which happens to be my favourite.

Credit: Debalina

Set around the 2018 decriminalization verdict, the film is an irreverent dig at the institution of marriage, with dashes of dark and dry humour. Perhaps so much so that the Indian Censor Board passed it only with an adults-only A certificate. But it also brings forth the sharp divides within Kolkata’s queer communities on whether marriage equality is the next big ticket to queer liberation or not.

Going back in time, Debalina worked on the 2000 release Satyer Araley (Veiled Reality), the very first Bengali TV documentary on queer issues, broadcast at a time when India’s queer movements were still in nascent stages. I was among those interviewed for the show, which was telecast on Tara Bangla channel. Though I’d been out in the media for many years as a queer activist, exposure on a Bengali channel was a first for me, too. What struck me was Debalina’s reassuring and sensitive approach, a far cry from the sensational style of many other journalists.

Satyer Araley helped Debalina interview and get to know members of Sappho, eastern India’s first support group for queer women. “This ended my search for answers to questions around my own sexuality, which I’d been struggling with since my years of comparative literature undergraduate studies and engagement with student politics at Jadavpur University,” she told Xtra in an interview. The association with Sappho set her off on a journey of queer filmmaking from which there’s been no looking back.

In the last 20 years, Debalina still hasn’t lost her sensitivity and sensibility as she wields the camera. She doesn’t identify as an activist, but is hard-headed, a vocal critic of homonationalism—queer people being accepted only if they don’t question the dominant ideology—and believes in aligning with larger civil rights movements. Since 2019, she’s been a visible part of feminist and citizen mobilizations to protest the Indian government’s moves related to citizenship, which have been criticized as anti-Muslim and unconstitutional. Because of that visibility, she was even a victim of right-wing violence, unthinkably, in her own South Kolkata neighbourhood. The police provided little support, but the day after the incident, a huge protest march was organized in the area by residents and students from all over the city.

“When I started making films, there was a lot to prove—to myself and to others. Today I see many others taking up cinematic activism,” she says. “With the Indian queer movements more than three decades old now, I’m fascinated by the diversity of the queer mobilizations unfolding across India today and would love to capture it on camera.” But given who she is, her next venture isn’t likely to be a gushing account of the pro-government queer groups that have gained considerable prominence in the last decade.

Rajib Chocroborty, 53, is a poet, schoolteacher and a survivor of prejudices against both queerness and physical disability caused by a road accident. Born in Imphal in 1968, he spent his childhood and adolescence in Shillong, a hill town in a nearby state, and moved to Kolkata in 1984. A lover of books since his childhood, becoming a writer was his dream, and his first poem was published in a college magazine. Kolkata, with its history of art and literature, stimulated his poetic sensibilities.

The city also provided him with the courage to come out as queer to his family and friends when he discovered Counsel Club, one of India’s earliest queer support groups (founded by myself), through a news story in the mid-1990s. “Till I joined Counsel Club, I’d always experienced an oppressive silence, unable to talk about my sexuality with anyone,” Chocroborty tells Xtra. “I tried to express myself through my poems, but that hadn’t helped either. Now, I could breathe easier.” He found greater acceptance at home, but was shunned by many friends because they said his sexual desires were “unnatural.”

The road accident, which happened in 2004, changed his life again when he almost lost both his legs. I was a witness to how both his natal and queer families rallied around him to provide medical, financial and emotional support. Above all, it was his own tremendous resilience that in time he was able to walk again and go back to work.

Chocroborty laughs when I ask him how he maintains an oceanic calm against all odds. “I’d rather describe myself as an angry and sad person,” he says. “I’m tired of being treated as a ‘good boy’ right since my school days. Good boys don’t fall in love, they’re not supposed to have sexual desires. One of my earliest poems, written when I was 15, which expressed desire for another man, drew a remark from a close friend that she couldn’t imagine me having such thoughts; this when the poem didn’t even mention the gender of my object of affection.” As a disabled gay person, the odds have been stacked even greater against finding romantic and sexual fulfilment, he says.

Credit: Partridge Publishing

These days, though, he’s savouring the success of his first two poetry collections, both published in 2021, A Different Shade of Green by Partridge Publishing, and Aakash O Pratibandhi (The Sky and a Disabled Person) in Bengali by Orange Publishers. The books have 60 percent of the poems in common, many of them translated by Chocroborty himself. Several of the poems were previously published in Kolkata’s queer publications like Pravartak (published by Counsel Club) and Swikriti Patrika since the 1990s. But he came into his own just last year, as the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdowns eased their stranglehold.

A Different Shade of Green, a mix of free verse, sonnets, ghazals (like an ode), limericks and haikus, can be many things to many people. For me, it provides an insight into Chocroborty’s thoughts and experiences as a disabled gay man, an intersectionality that still hasn’t gained deeper attention within the queer and disability movements in India.

“As a physically disabled queer poet, I feel put away in the corner, sometimes literally,” he says. “Especially in terms of my disability in queer circles—I can’t have access to the queer literary discourses because I’m unable to attend many of the literary events.”

Though Chocroborty teaches and writes English literature, he suspects his students and colleagues are unlikely to be interested in what he writes. “Anything that is beyond the syllabus is of little interest to most teachers and students,” he says. More important, though, the precedent of queer teachers in Kolkata losing their jobs in recent years on grounds of their sexuality or gender expression, and his school’s location in a semi-urban area, worries Chocroborty. “If the school authorities come to know about my sexual orientation and do pay attention to what I write, I can’t rule out a homophobic response.” And yet, there’s no calming down his creativity.

From A Different Shade of Green:

An Online Affair

I presume you are being cruel only to be kind.

I’m steadily moving down in your list of favourites

and your silence is growing louder.

You may think after shedding a few tears

everything will be fine.

But it does hurt.

And you are starving to death

the life that has been growing within me

for the sake of which I was about to

loosen the bonds that have kept me alive.

Rudra Kishore Mandal, 44, dropped out of studying commerce in Kolkata, against the wishes of his parents, and went off to the southern Indian city of Hyderabad to graduate in fine arts in the 1990s. “But art wasn’t the only thing on my mind,” quips Mandal. “A new chapter started for me as a queer person when I also became part of Saathi, a queer support group formed in the mid-1990s, possibly the first of its kind in Hyderabad.”

Later, Mandal’s job as a graphic designer took him to Mumbai and Delhi. He returned to Kolkata in 2008 to create independent artworks through the varied mediums of painting (using watercolour and pen drawings on paper), digital graphics and art installations, sometimes accompanied with poetry, another of his passions.

Credit: Rudra Kishore Mandal

Eventually out to everyone at home, he also quickly entered the thick of queer activism in Kolkata. In 2011, he co-founded a queer collective called the Kolkata Rainbow Pride Festival (KRPF). For the next eight years or so, KRPF was the prime force behind organizing the Kolkata Pride, which grew fast and attracted nearly 5,000 participants in 2017, an impressive number in India.

KRPF included only queer individuals and allies, and Mandal was a vocal proponent of keeping out queer community groups, NGOs and corporate agencies, because they often tended to prioritize organization over cause and community. Indeed, Mandal and his colleagues were instrumental in making the Kolkata Pride free of all organizational banners, logos and promotional material, including those belonging to the KRPF itself. This was quite against the tide of corporatization impacting many other Pride marches in India.

Mandal was also the live wire in organizing KRPF’s parties for raising community funds to organize the Kolkata Pride, and brought his artistic sensibilities to the party décor and music as well.

“My creations reflect personal explorations into subjects that interest me, but they’re also about going against the norms and the struggles involved in doing so, whether it be gender, career choices or artistic styles adopted by my contemporaries,” he says. Indeed, if I need a graphic to illustrate an anti-establishment stance through Varta’s social media posts, Mandal is the first artist I turn to. His intricate creations fascinate me for the stories they tell through the mythological characters and folklore of Bengal, and elsewhere.

In his youth, Mandal has had struggles both around being queer and an artist: “My parents and extended family felt that the arts couldn’t be a profession for a man. I was supposed to get married and have children. How could the arts have helped me earn enough to maintain a family? I had to move away to a different city to make a mark for myself.” Later, the label of “queer artist” added to the challenges around exhibition opportunities, venues and censorship.

“I want my art to be ageless, accessible to all and enable people to introspect and broaden their thinking.”

Yet, Kolkata’s willingness to explore the bohemian has led to new opportunities for Mandal. He participated in the Kolkata International Performance Art Festival organized by Performers Independent, a collective that experiments with traditional, modernist and contemporary art forms and spaces. The festival, organized annually between 2013 and 2019, was transformative for Mandal. “During discussions among artists, not once was I made to feel like an outsider as a queer person. The best part was that the festival took place in both private and public spaces, such as the streets of Kolkata. We could use not just the walls in the private spaces, but also the windows and ceilings, and in public places, we were right there in the middle of the viewers. This drew in a much wider audience than usually happens in traditional art spaces.”

Mandal has also had international exposure through an exhibition called The Liminal, organized by Queer Asia, the British Museum and SOAS University of London in 2019. The exhibition aimed to provide an insight into how queerness is imagined and experienced in different Asian contexts.

Clearly, family, community and social or cultural institutions have not managed to contain Mandal’s spirit or art. “I want my art to be ageless, accessible to all and enable people to introspect and broaden their thinking,” he says.

Up next for Mandal is his first solo painting exhibition. In the meantime, he is also providing creative insights to Charu, a design and fashion line launched by his sister Prabhati Mandal and friend Prithviraj Nath. Charu uses textiles and crafts from the eastern and northeastern regions of India and focuses on creating genderless clothing and accessories.

All of this is a work in progress, as is the city of Kolkata.

Clarification: August 8, 2022 10:16 amThis story has been corrected to better reflect the roles at Charu.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra