This story is part of a series of travel and culture features spotlighting London, U.K., this summer.

Queer Britain, the U.K.’s first museum exclusively showcasing LGBTQ+ art and history, opened in London last month with an inaugural show of photography spanning more than 100 hundred years. The exhibition—a mix of archival and contemporary images—was put together by Matthew Storey, a curator with Historic Royal Palaces.

“It’s to welcome people to the first brick-and-mortar home of the museum and to celebrate the museum’s achievements so far,” Storey says over Zoom from London.

Earlier this year, Queer Britain moved into a Victorian warehouse in London’s revitalized Granary Square, located alongside a canal near King’s Cross railway station. Neighbours include the Central Saint Martins art school, Drama Centre London and the Regent’s Canal Towpath park. “It’s an incredible time to be in King’s Cross,” Storey says. “It’s a real cultural hub now around Granary Square.”

Credit: Courtesy of Queer Britain

Queer Britain began four years ago, the brainchild of Joseph Galliano, former editor of Gay Times. After seeing the success of a queer art show at the Tate Modern, Galliano realized there was pent-up demand for exhibitions exploring queer and trans art and history. He soon partnered up with the U.K.’s National Trust, the Tate, creative agency M&C Saatchi, the visual media company Getty Images, among others.

While fundraising and building the team, Queer Britain began connecting with audiences through a series of stand-alone exhibitions. “The current exhibition is partly things that people might have seen before,” Storey says. “It’s a chance for people to celebrate what Queer Britain has already done.”

The exhibition features selections from previous QB efforts like Chosen Family, a pop-up exhibition in Covent Garden in 2019, and The Madame F Award, an open competition sponsored by the wine label created by QB and M&C Saatchi in 2021.

“My favourite piece,” Storey says, “is one of the first things you’ll see, from the Getty Images collection: a Victorian photograph of two music hall performers, two women dressed beautifully in men’s clothes. I wanted to get something really early because I wanted to show how queer people have always been a part of every human society.”

The exhibition, continuing until July 4, isn’t the museum’s inaugural show, per se; occupying only three rooms, it’s considered a preview. The museum’s as yet unnamed opening show is scheduled for July 20.

“In the current exhibition, we’re also showcasing new acquisitions, because the museum is actively acquiring,” Storey says. “So, we wanted to have some contemporary works that people wouldn’t have seen before.”

The contemporary pieces include portraits by photographers Robert Taylor and Allie Crewe. Among the latter’s work is “Grace,” which won the British Journal of Photography’s Portrait of Britain Award in 2019, part of a series of portraits of trans and non-binary folk called You Brought Your Own Light.

“That portrait is so beautiful. It’s so human,” Storey says. “We keep saying it looks like a modern-day Vermeer. It really calls to mind very classic histories of image-making, yet it feels so fresh and contemporary.”

With many of the archival images, much mystery still surrounds exactly what is being depicted. Storey cautions against imposing our modern sensibilities onto the past.

“I am doing this as a volunteer, separate from my work for Historic Royal Palaces,” Storey says. “In my day job, very often I’m dealing with art and objects from hundreds of years back. That experience has led me to always look at the past with an open mind.

“Understanding of gender and sexuality was different in the past; social constructs were different in the past; vocabulary, terminology were very different in the past. And being very aware of that, I don’t like to retrospectively apply the labels that might work for us today to people in the past.”

And yet, giving a queer reading of some of these image is too tempting at times. Storey has a delightful way to describe how he approaches that relationship with archival images. “Something I say over and over again: when you look at a photograph of a crowd scene from the 19th century, or a wall of portraits, one thing you can always be sure of is that not all of those people are straight.

“There was just as great a diversity of sexuality and gender identities and experiences in the past as there is today.”

Credit: London Stereoscopic Company/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

“It’s so important to remember the long histories of queer and trans lives and identities, which have always been an essential part of the human experience,” says Queer Britain curator Matthew Storey. “We don’t know how these two immaculately dressed Victorian music hall performers may have seen their own identities, but their style is part of an important theatrical heritage.”

Credit: Hulton Archive/Getty Images

“Looking at images from the past can raise as many questions as answers,” Storey says. “What were these young men, who were probably soldiers, feeling with their crossdressing? Perhaps this chance for some queer self-expression provided some light relief during the First World War.”

Credit: Courtesy of Queer Britain

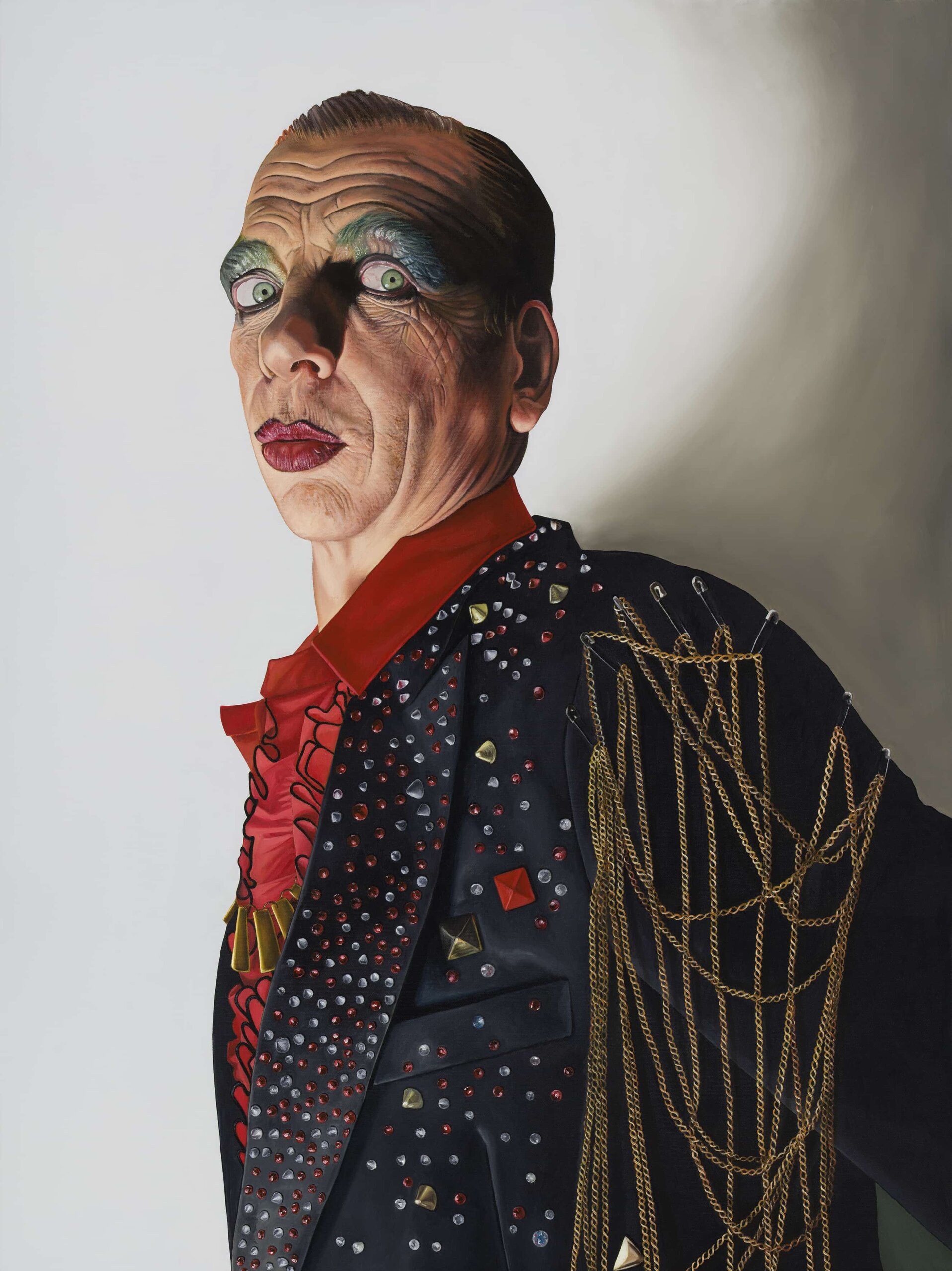

One of the few painted works in the Queer Britain exhibition is of performance artist David Hoyle, painted by Sadie Lee. “David Hoyle is a legend of the queer performance scene, and this portrait shows you why,” Storey says. “His performances are uplifting, creative and uncomfortable. It’s a formidable painting, and the first image you see in the opening display. It won first prize in the inaugural Queer Britain Madame F award on the theme of ‘queer creativity.’”

Credit: Allie Crewe

“We keep saying it looks like a modern-day Vermeer,” Storey says. “It really calls to mind very classic histories of image-making, yet it feels so fresh and contemporary.”

Credit: Courtesy of Queer Britain

“Part of a Queer Britain pop-up project in summer 2019, Alia Romagnoli’s portraits reponded to the theme ‘chosen family,’ reflecting the important communities queer and trans people build around shared identities. Alia draws on her South Asian heritage in these beautiful images, and I love how their vibrant colour brings a sense of the joy and beauty of queer experience.”

Credit: Courtesy of Queer Britain

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra