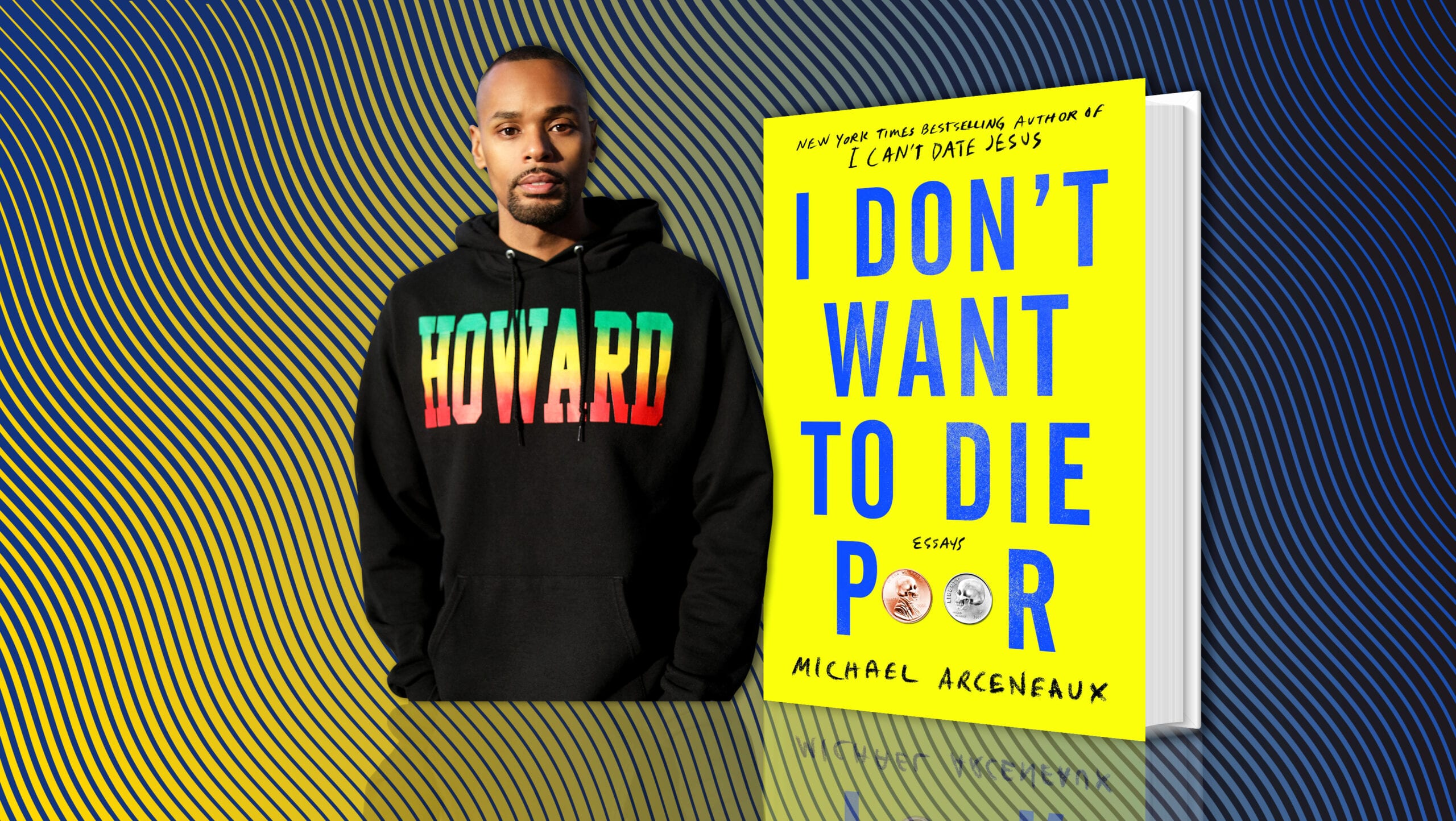

Michael Arceneaux, The New York Times bestselling author of I Can’t Date Jesus, is a Houston-born, Beyoncé-loving writer now based in New York City. His words have been featured in just about every publication, from The Guardian to Buzzfeed, and his unique brand of social commentary has led him to being named one of the best Black bloggers to read and one of the top #BlackTwitter voices to follow. “I’m turning into Iyanla Vanzant or Yoda with age,” he says, “which is fine because I feel like both of them carry a blade.”

With his second book, I Don’t Want to Die Poor, Arceneaux turns his attention to his struggles with debt. Based on his New York Times op-ed, “The Student Loan Serenity Prayer,” the essay collection details how money has impacted every facet of Arceneaux’s life and explores the paradox of social mobility.

As the world grapples with our ongoing new normal due to the continued spread of COVID-19, the publication of new books like Arceneaux’s, which was released Apr. 7, are in jeopardy. Like others in creative industries, Arceneaux looks on with trepidation as barriers to success grow exponentially. “I’m worried,” he says, “but the moment is bigger than me.” As a Black, gay author who doesn’t centre white people in his work, Arceneaux admits that it’s sometimes difficult to gain access to the largest possible audience. That means, he says, he has to be mobile and get the word out himself.

“A lot of people have been saying how my book is so timely now, in light of the pandemic,” he says. “But my book was timely before this: [It addresses] why there’s a pandemic, and particularly why the pandemic is so much worse in the United States despite us having all of the resources in the world.” While the book is timely, Arceneaux adds it’s “minus the doomsday plot and the racist game show host president.”

I spoke with Arceneaux about his first two books, discomfort when talking about money and ideas put forth by U.S. politicians running for president about student loan debt.

When you first found out that I Can’t Date Jesus made The New York Times bestseller list, what was your reaction?

It was important to me to make the list and I’m really glad I did, because it wasn’t just me. It’s Samantha Irby and Darnell Moore. It’s DeRay Mckesson. It’s so many other people. But I do know that that success wasn’t just mine: It helped make it easier for other people to get book deals, and to get book deals better than mine. So it felt good. But you know, at the same time, I had lost my health insurance and was high as fuck on the elliptical, just trying to escape for a minute.

How did you settle on using your debt experiences for the subject of the second book?

I knew I wanted to write about student loan debt in some way, I just didn’t know when I was going to talk about it because, to be blunt, it’s very uncomfortable to talk about money and struggling with debt. I wrote this essay for The New York Times Sunday Review about private loan debt just to kind of see my own level of comfort, and to see if there was actually an audience for that. Because I think so many of the narratives about debt is basically like: “I sacrificed for 96 years and didn’t eat for nine hours out of the day and now I have no debt,” which is stupid. I wanted to shift the narrative, and people were receptive.

In the book, you talk about sacrifices you made to be a writer. Why was it important for you to include that?

A lot of people in media and entertainment, Black included, don’t recognize and don’t verbalize the fact that most people—in the same way that white people can afford the sacrifices required of this industry—do not pay people what they deserve. The few Black people that are in these spaces are usually middle class, which is very much a privilege in and of itself. I am not a middle-class child. And so when I hear these stories from Black people in entertainment, I don’t think they really acknowledge the fact that you came from a nicer setting than most. So while it’s not to take away from the fact that you worked hard, you need to add the fact that you had a little bit of a boost.

I’m always cognizant of the fact that I am very lucky to be in every space, even the ones that I’m complaining about. Even though I did not get what I thought I deserved for that first book, it worked out for me in the end because at least I can get royalties now (please keep buying this shit). But at the same time, I know white boys less than me on paper who got [a better deal] than me and sold less. It doesn’t matter. It’s just not fair, but I have to deal with that. I think more people need to be honest about that sacrifice and be willing to say “I had to struggle.”

Say more about that, because you’re one of few people who are public about their difficulties in this way.

I could easily just say, “Oh, I worked hard.” But that’s a bullshit story. I know I’m on a tangent now, but I need people to really know it’s hard to really get out of your situation. I Can’t Date Jesus is about learning to be yourself and allowing yourself to have that freedom to live. But freedom is also really expensive. Your life is often determined by how much money you bring in, who you’re connected to and whether or not there’s somebody else who can help you actually get connections, people who can get you real money, real social mobility. I think more people really need to talk about that, particularly the proximity to whiteness and how much that plays a role in their success—I’m one of the few people who comes from Black media but who has written for white people and still gets to be in white spaces. That is a lot harder than people say or recognize.

You mentioned how people generally aren’t comfortable talking about money. I feel like that’s compounded for Black folks. Are you now comfortable talking about it after writing this book?

I would say that it doesn’t necessarily make me more comfortable, but I’m more willing to do something that makes me uncomfortable for the sake of the greater good.

You talk in the book about your student loan debt, which I feel like I’ve always been told is the “good” debt to have—that is, until loan company Sallie Mae comes knocking six months after graduation. In what ways would you say your student loan debt has prevented or curbed your ability to live, thrive and to be part of this social mobility thing?

I had the chance to have my dream job, to work under the editor-in-chief of Vibe magazine. But it only paid $28,000. I was willing to do the work, but that was not going to help me be able to live in New York City, no matter how I tried to swing it, on top of paying those private loans that did not allow me any grace. So I made a choice that maybe in hindsight I shouldn’t have made. That job could’ve changed the trajectory of my life, but I couldn’t take it because it fundamentally was going to have me defaulting [on my loans] from jump, which would have potentially hurt me from trying to rent my own place, to be in the city, to get certain access.

But even with that dream job, you have to be able to afford to sacrifice, to accept it. You have to be fortunate to suffer through whatever you’ve got to do to get through that. So I asked to move back home instead and figure out how to support myself as a writer. I had to humble myself and figure out a way back out, because I couldn’t take that job; it just was not going to work. Some people might have chosen a different path, and that’s perfectly fine. But you can’t say that my choice wasn’t reasonable because I’m still taking a risk, but I’m just being more calculated about the risks.

And those calculations never stop.

I don’t love freelancing, but the first financial crisis of my adulthood put me in that situation, along with the [ever-changing media landscape]. Like, I have to make a certain amount of money to function and I was very adamant about my second book—I got more money. I got what I felt I deserved. But that was from having a conversation with another author who told me what she got, and now I talk to people about what they should be asking for. That’s how we, particularly non-white people who do not have any real space in that world, can learn how to start getting what we deserve.

There’s a lot of blame lodged at younger people for our country’s economic woes because, apparently, we spend too much money on avocado toast. But what do you think the broader public just doesn’t really understand when it comes to some of the personal debt we’re dealing with that prevents us from, for example, buying a house?

People fall for the okie-doke: They really believe in this idea that life is a meritocracy. Sometimes I also think a lot of people not only hope to be rich, they hope to be as greedy and awful as the rich people are now. And it’s such a ridiculous concept because if you really took time to think about it—and most people don’t really think enough about it, sadly—the idea of you becoming these rich people that you aspire to be is highly unlikely, because the system is designed for you not to catch up. And so when people try to say, “Oh, you took out this debt, blah blah blah blah.” Well, you know what? If I didn’t take out this debt, I wouldn’t be talking to you right now. The problem is, I shouldn’t have had to take out that type of debt to do anything.

In the book, you go through a lot of the other careers that you contemplated or tried out as you were looking for success and consistent coin as a writer. I’m wondering which one might you still try at this point in your career?

Well, I definitely can’t be a Republican plaything now. I actually still might just have to go rap. I mean, I’ll be 36 in a few weeks. But, you know, bars. Or I can go back to having pretty feet and be a Big Toe Hoe if all else fails. I respect that work. You do whatever you have to do to survive.

Some people have been saying that your book is even more timely right now because a lot of student loan and debt conversations are happening this election year. What are your thoughts on the discourse that we’re seeing among our politicians right now?

I liked how Bernie Sanders and Liz Warren talked about debt cancellation. I leaned more towards Bernie, but Liz still would have helped a lot of people. Either way wouldn’t impact me at this point, I don’t think, but we need to cancel debt. It would generate revenue. If you’re not talking about real debt cancellation, you’re not being serious.

I implore the Joe Biden campaign, who could use every boost of energy, ginseng and whatever else, to talk more about debt cancellation. That is a real issue. And honestly, so many people are already hurting, but they’re going to be hurting so much more [in the midst of and after this pandemic]. And these companies—particularly these private student loan companies, which none of these politicians talk about enough nationally—are going to be even more awful to you because they don’t care. I just can’t deal with Sweet Potato Saddam again, so I need Joe Biden to pull it together.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra