Whatever women do they must do twice as well as men to be thought of as half as good. Luckily this is not difficult. — Charlotte Whitton

Often working in politics means covering up significant parts of your personal life. You know all those drunken/topless photos floating around Facebook? Not so funny when you’re a public figure. But as much as politicians nowadays mustn’t reveal too much of their less-than-professional activities, the consequences of discovery must have been infinitely more serious for a lesbian mayor of Ottawa in the 1950s and ’60s.

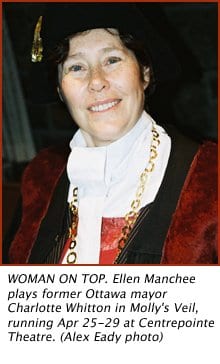

In Molly’s Veil, playwright Sharon Bajer explores the distinct public and private lives of feminist Charlotte Whitton, the first female mayor of a major Canadian city. Local actress and historian Ellen Manchee plays the lead role in the GOYA Theatre production.

“As a historian, I am very attracted to historical theatre,” says Manchee. “Charlotte is such a fascinating character. Before her, the municipal government hadn’t seen such a strong woman in politics. Then women continued to be even stronger — she was a pioneer of that.”

On one hand, Whitton was reputed to be a rather conservative municipal leader: she believed that women had to make a choice between marriage and a career, and they should not continue to work once they were married. She also cared little for progressive views on abortion, divorce and sexuality.

“Her ideas were typical of the time. She wanted immigration controlled. She considered unmarried women with children weak and inferior,” says Manchee, sharing details from her research.

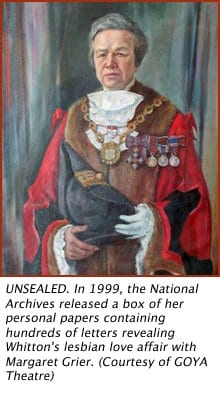

On the other hand it has been discovered that Whitton may have been engaged in a long-term lesbian relationship with her friend of over 30 years, Margaret Grier (played by Stephanie Haines.) In 1999, more than 20 years after Whitton’s death, the National Archives of Canada released a box of her personal papers containing hundreds of letters — arguably of a romantic nature — to her dearest companion and housemate.

Before these letters were revealed, it was assumed that Whitton and Grier lived in what the Victorians would describe as a “Bostonian marriage.” It was deemed socially acceptable at the time for women, either spinsters or feminists who chose career over marriage, to live together. But the term never implied anything romantic in the relationship.

“There’s no question they had an intense romantic love. Was it a physical love? That, we can only guess. But it was certainly passionate. Charlotte wrote letters even after Margaret died that said things like, ‘Oh Marty, I miss you so. I didn’t deserve you.’ It was a passionate grief,” says Manchee.

The play itself details Whitton’s inaugural appearance as mayor in 1951, and dramatizes an interview between the new mayor and a young journalist (played by Rachelle Casseus). During this interview Whitton slips back into memories of her relationship with Grier, who, at the time of the play, had recently passed away. Manchee says the play is less about politics and more about the relationship between these two women.

“It’s about love,” says Manchee.

Manchee admits that she struggled with Whitton’s apparently contradictory lifestyles when it came to developing her character. After all, the two women kept Lent and communion: could they have been both religious observers and lovers?

Whitton’s relationship is not something that would have been discussed openly around the municipal water cooler.

The question remains: why did Whitton ensure that these letters were concealed for so long, even posthumously? Manchee suggests that perhaps Whitton wanted to be remembered first and foremost for her political achievements, and not simply for her personal life. But then, why were these letters revealed at all?

“She likely imagined there would be a time when her relationship would have been accepted. She wanted it to be known,” says Manchee.

And that is something very beautiful to consider.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra