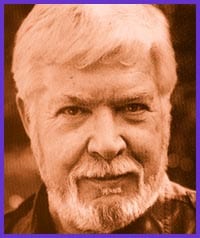

Flip over Timothy Findley’s ninth novel and his greybeard face peers at you with a gaze both penetrating and mischievous. To those young enough to be just discovering this bracingly queer lion of CanLit, he may, at 69, look like a slightly dissolute grand-dad. But I still can’t look at any photo of Findley without seeing the irrepressible daydreaming kid, helplessly imagining worlds.

Pilgrim was on the bestseller lists even before its official release date, and its flood of vivid imaginings will likely keep it there. It blends fiction, history, dreams and madness into a panorama of events and historic figures, all linked by the tormented mind of one ornery, mysterious, possibly insane man.

Pilgrim is unable to die – and not for want of trying. Following his latest failed suicide in the garden of his London house in 1912, he finds himself in the care of famed Zurich psychiatrist Carl Jung, transported there by a beautiful woman who is both infatuated with him, and attuned to a mystical quality in him that she hopes Jung might be able to explain.

Pilgrim, who has no apparent birthplace or family, at first refuses to speak to Jung or anyone else. But Findley makes us privy to his thoughts, which provide a revealing and tart counterpoint to the mechanical probing of Jung’s clinical method. The uneasy dance of these two men – one, the voice of arrogant, plodding authority, the other, a voice of riddle and evasion – provides the backbone of a story stretching from the seige of Troy to the carnage of World War I.

Pilgrim is desperate to escape “the dread necessity of self.” It becomes clear to us, if not to Jung, that he has simply seen too much history, experienced too much injustice and stupidity. Entering his mind and his journals, we witness a cavalcade of the famous and infamous: a callous Leonardo Da Vinci, a ruined and moribund Oscar Wilde, a Teresa of Avila bemused by her own saintliness, a thief who steals the Mona Lisa. We walk through Paris with Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas, view the tyranny of Savonarola in medieval Florence, and meet Gustav Mahler over dinner.

Pilgrim confirms Findley’s gift for evoking eras and places. He can make a room or a landscape spring fully formed into the mind. His dialogue is invariably sharp and involving; his characters portrayed with wit and affection.

The pleasures of this book unfold moment by moment, in scenes like deftly painted miniatures. But as the story leapfrogs through history it begins to seem too far-fetched, and finally just oddly unfocussed and disconnected, as if Findley couldn’t bring himself to cut cherished parts for the sake of defining and polishing the whole.

The spirit of this book remains moving. It’s about finding a will to live, and knowing that it can be found only in grappling with whatever life presents. Passivity is the ultimate failure. Pilgrim puts it most memorably in his final letter to Jung: “What life requires of one is that one live beyond the endurance of it.”

Pilgrim.

By Timothy Findley.

Harper Flamingo.

486 pages. $35.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra