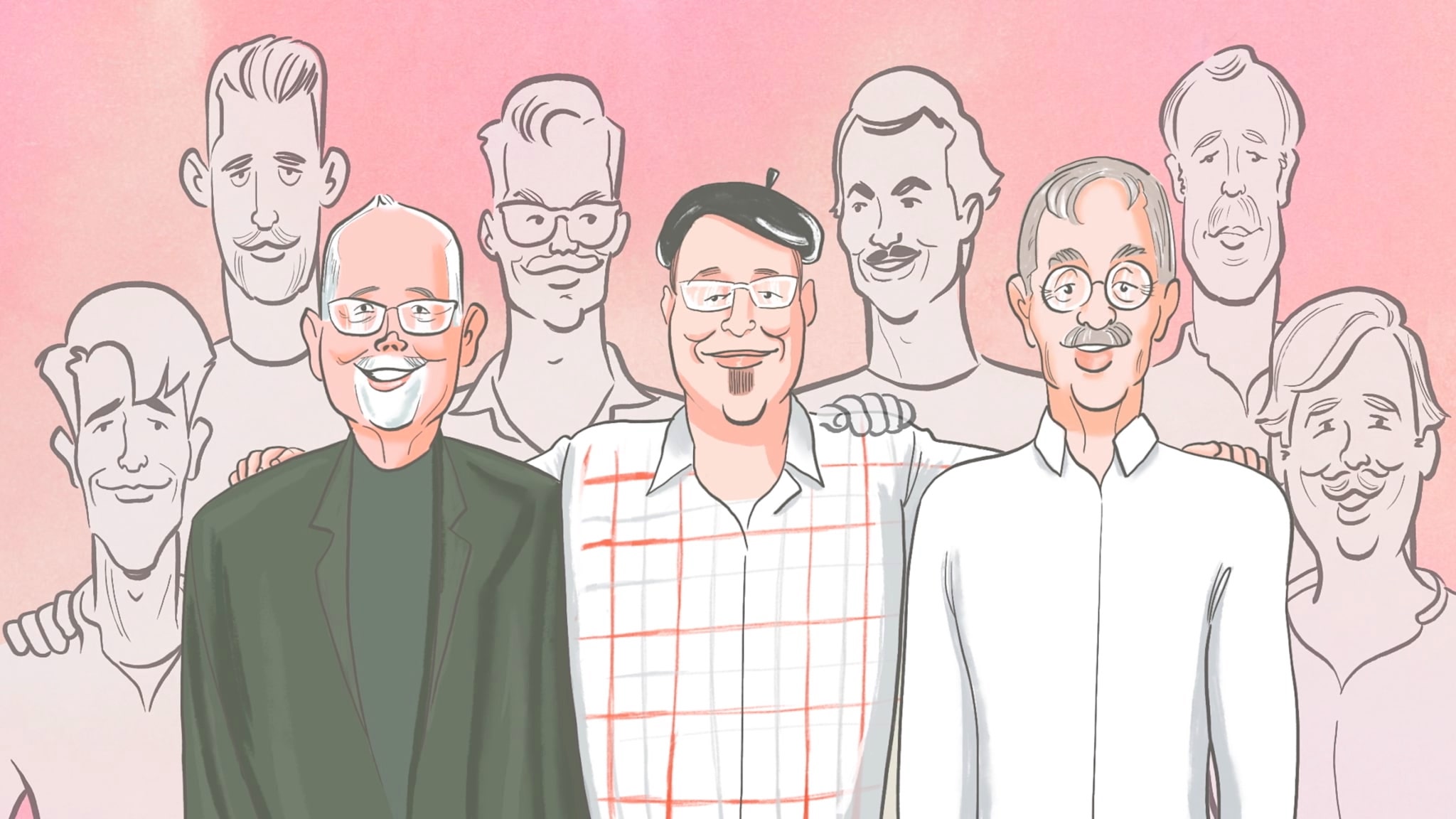

On Monday afternoon, May 9, Gerald Hannon took his last breath. He chose to end his life with medical assistance (what we now call MAID), a decision very much in keeping with the way he chose to live his life: on his own terms. I was with Gerald at the very end, along with two other close friends, Peter Kingstone and Gerry Oxford.

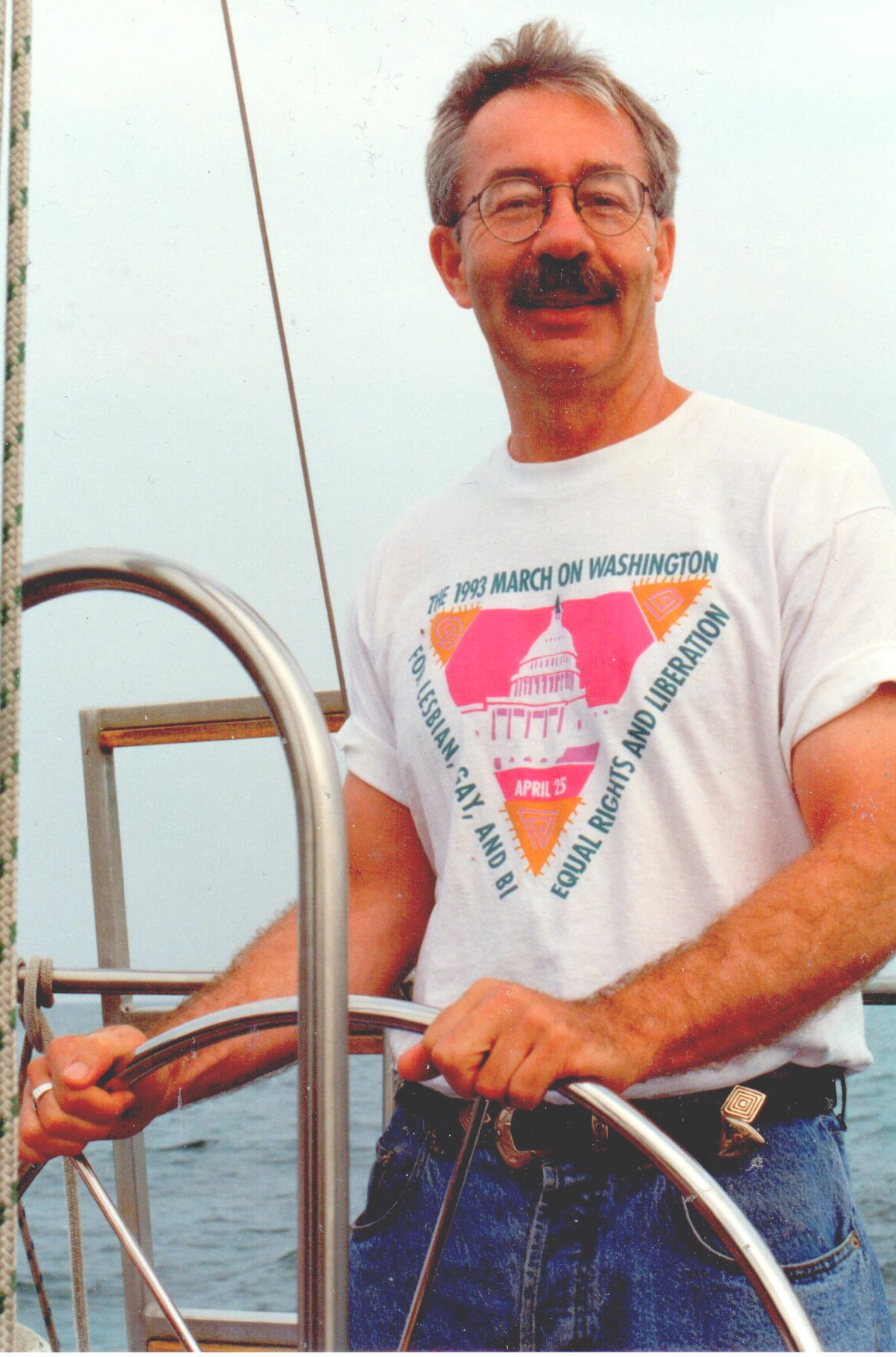

Four years ago, Gerald began to exhibit signs of atypical Parkinson’s disease, which progresses more quickly than regular PD. By April, he was needing daily help in showering, dressing and eating. He could no longer type or manipulate a mouse. He experienced intense fatigue such that he no longer felt even like listening to classical music, once one of the great loves of his life. Gerald’s memoir, appropriately titled Immoral, Indecent & Scurrilous: The Making of an Unrepentant Sex Radical, will be published this summer by Cormorant Books. Although he was not able to hold a final copy of the long-delayed book in his hands, he did get to see a special advance copy. It was enough to confirm his decision to end his life before it became unbearable, an option made possible because of recent changes in Canada’s MAID legislation. Great performers always know when to exit the stage.

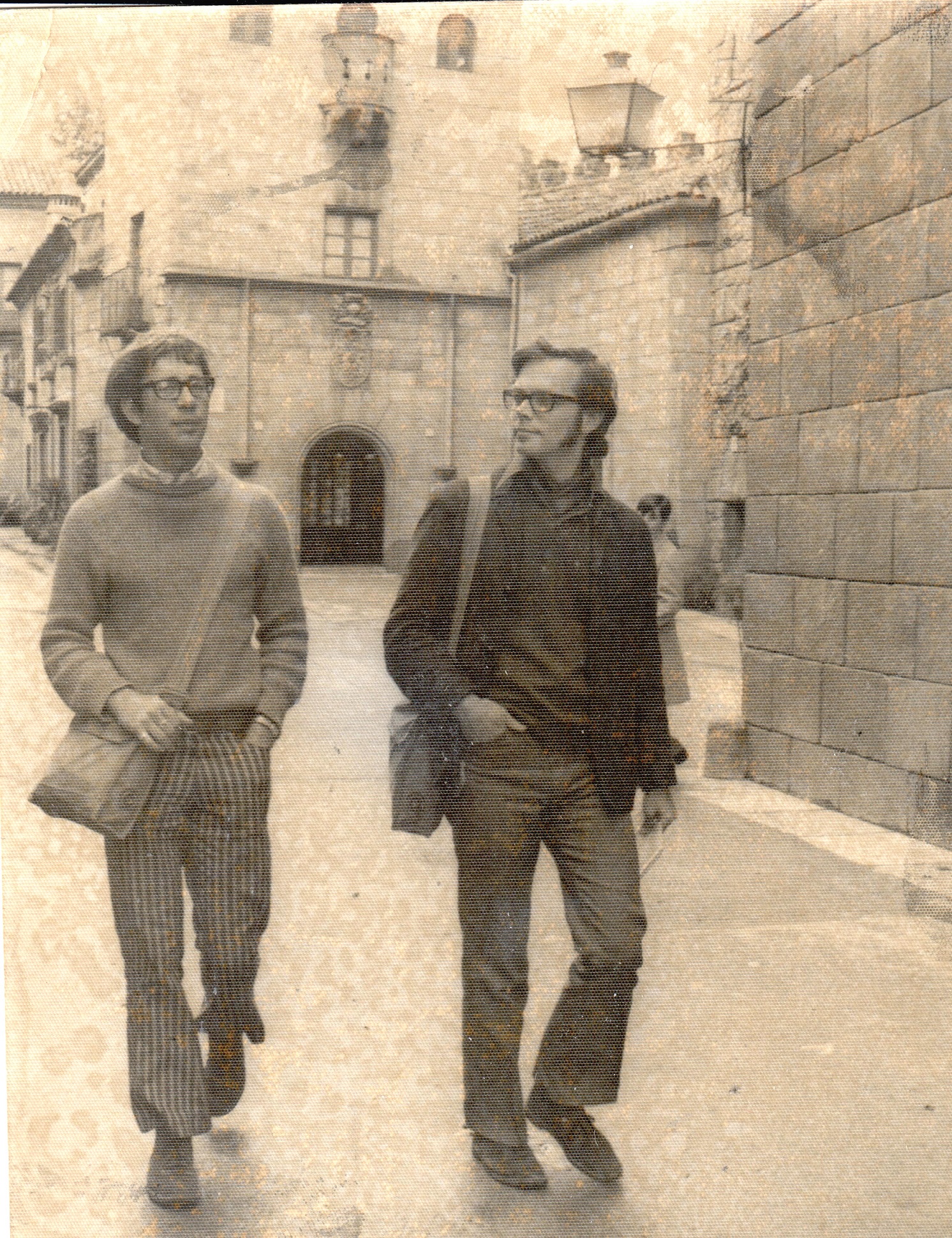

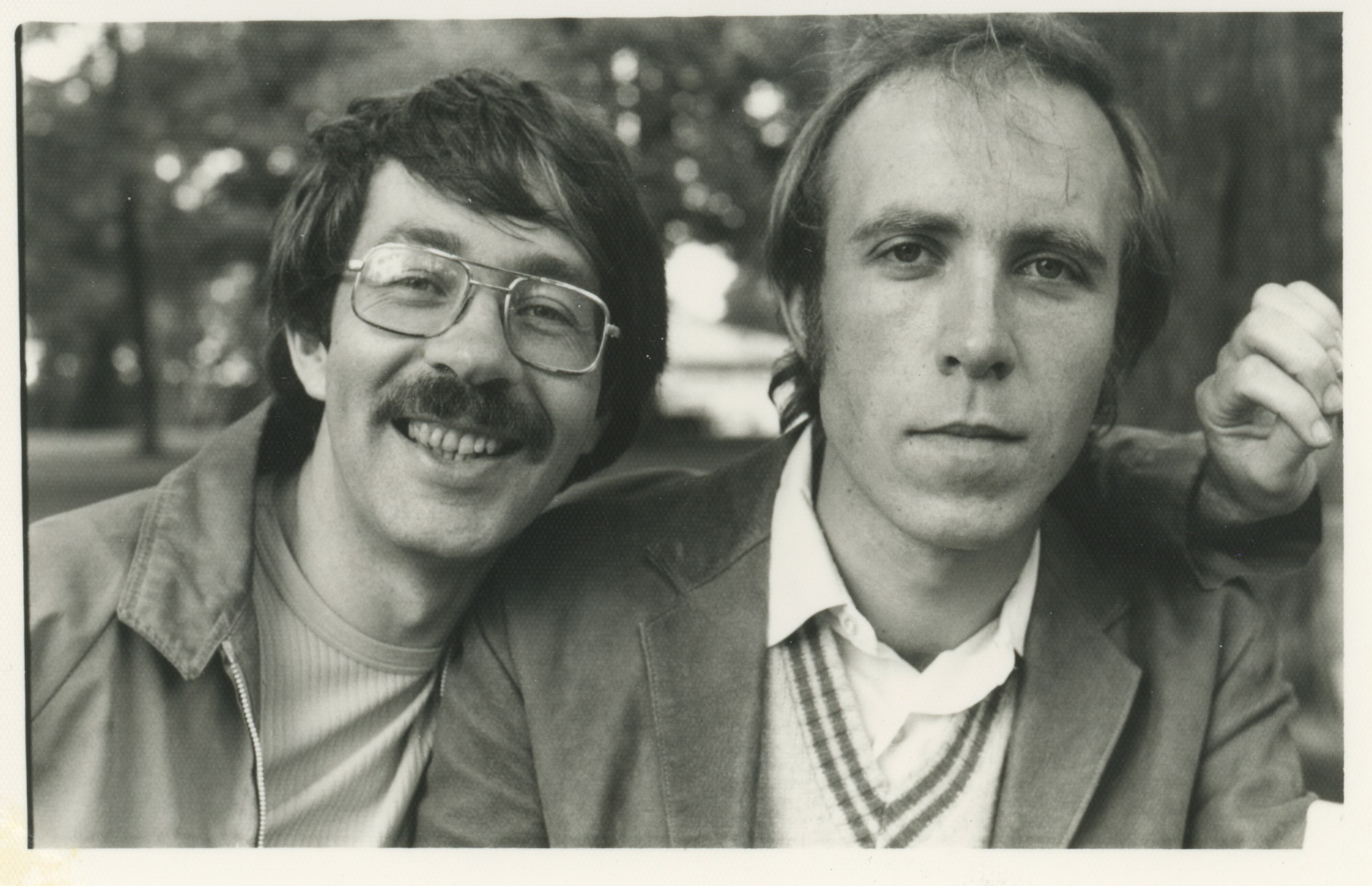

Gerald was my oldest friend. We met 54 years ago, in March 1968, when we both got hired, with zero training, as teachers of English as a second language to adults. We have shared so many experiences since that time. In 1970, we spent a year travelling together in Europe, where we participated in our first public gay demonstration. It was in August 1971; a march on Fleet Street in London to protest homophobic coverage in the English tabloid press. It was a scary as well as exhilarating experience, and soon we were back home in Toronto, eager to plunge into the emerging queer movement here.

Credit: Courtesy of Ed Jackson

And get involved we did. We joined the editorial collective for issue two of The Body Politic, the pioneering gay liberation journal. Gerald honed his skills as a writer in those early years, writing every kind of article or story that the fledgling journal needed to have written. As he notes in his memoir: “My career was shaped and served by words.” He became not only our best writer but also our main photographer, after learning to develop his own negatives and contact sheets. We lived the quintessential 1970s life: we shared a communal house; we cycled everywhere; we belonged to a food co-op; we joined countless queer demonstrations and protests.

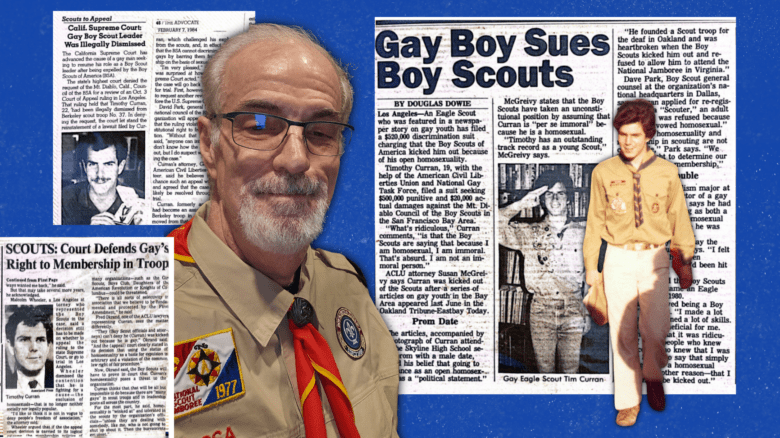

Gerald had an unerring ear for the best phrase, as well as an occasional instinct for the sensational in his writing, coupled with surprisingly little awareness of possible consequences. His article exploring intergenerational sex, “Men Loving Boys Loving Men,” got The Body Politic into a heap of trouble. We were charged with “use of the mails to distribute indecent, immoral and scurrilous literature” and the ensuing high-profile trial transformed the paper into a never-ending legal case as well as a magazine of record. Ultimately, the charges didn’t stick and we were acquitted of criminal charges three times.

Credit: The Body Politic

After The Body Politic ceased publication in 1986, Gerald looked for new ways to survive. He taught journalism part-time at Ryerson University [now Toronto Metropolitan University] and began to dabble in sex work for extra income. He was good at both, charming his students and offering a non-judgmental “courtesy boner” to the male clients who ended up at his door with an infinite range of sexual needs.

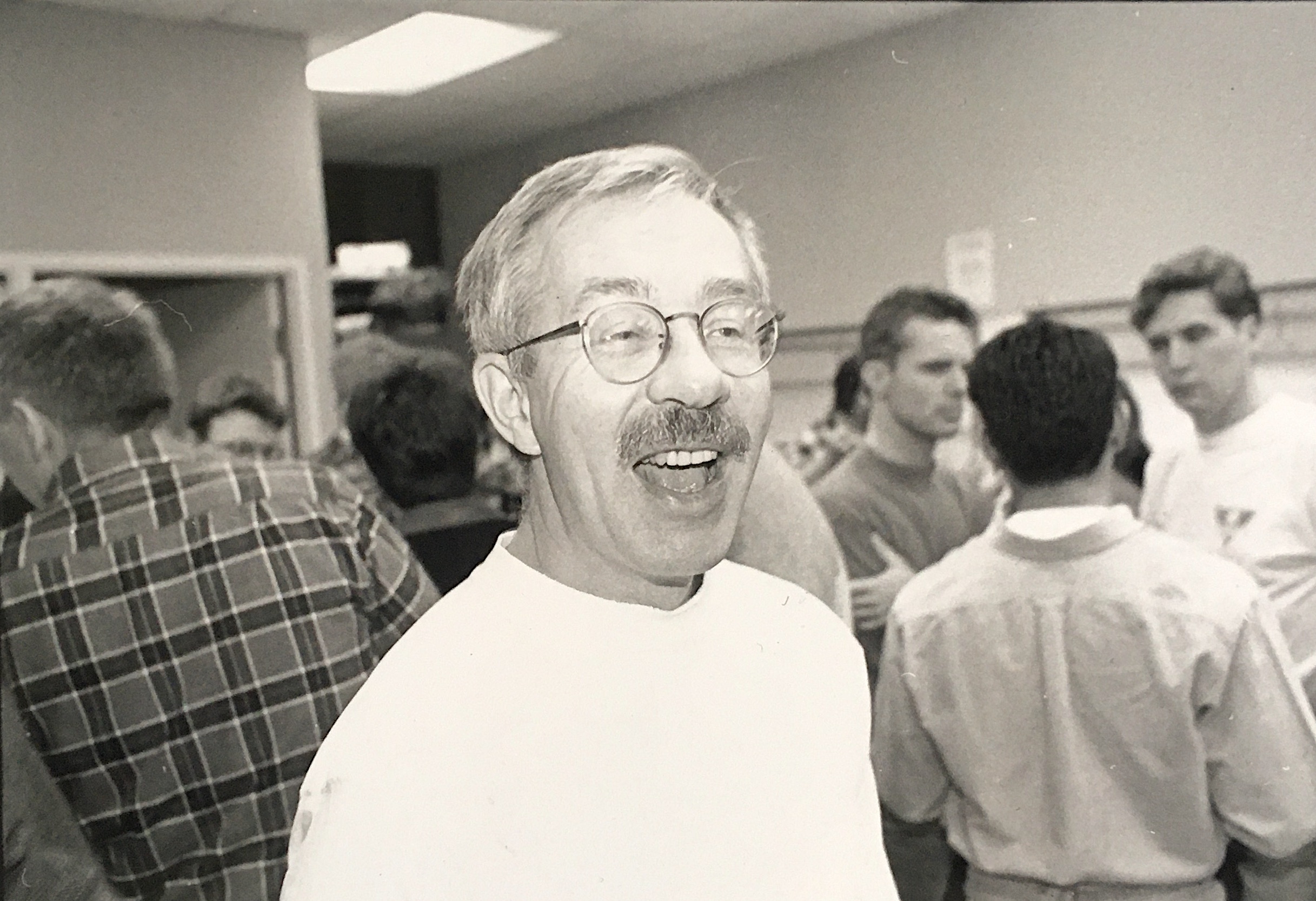

Gerald became a media sensation in 1995 after the child-sex-abuse-obsessed writer Judy Steed, remembering his earlier sympathetic writing about pedophilia, learned to her horror that he was teaching at Ryerson. Following his own advice to his students never to resort to a “no comment” evasion, Gerald responded truthfully to a Toronto Sun reporter who asked if he was a sex worker. Next day’s front-page headline, “Ryerson Prof: I’m a Hooker,” launched the media ruckus that rocked Ryerson and turned the life of “proftitute” Gerald upside down for months. Toronto journalists could scarcely believe this courtly, 50-year-old man was a self-declared sex worker who gave cheeky, quotable responses during packed press conferences. Finally, Ryerson bureaucrats, alarmed at a growing bleed of risk-averse corporate donors, cut their losses and terminated Gerald with a financial settlement.

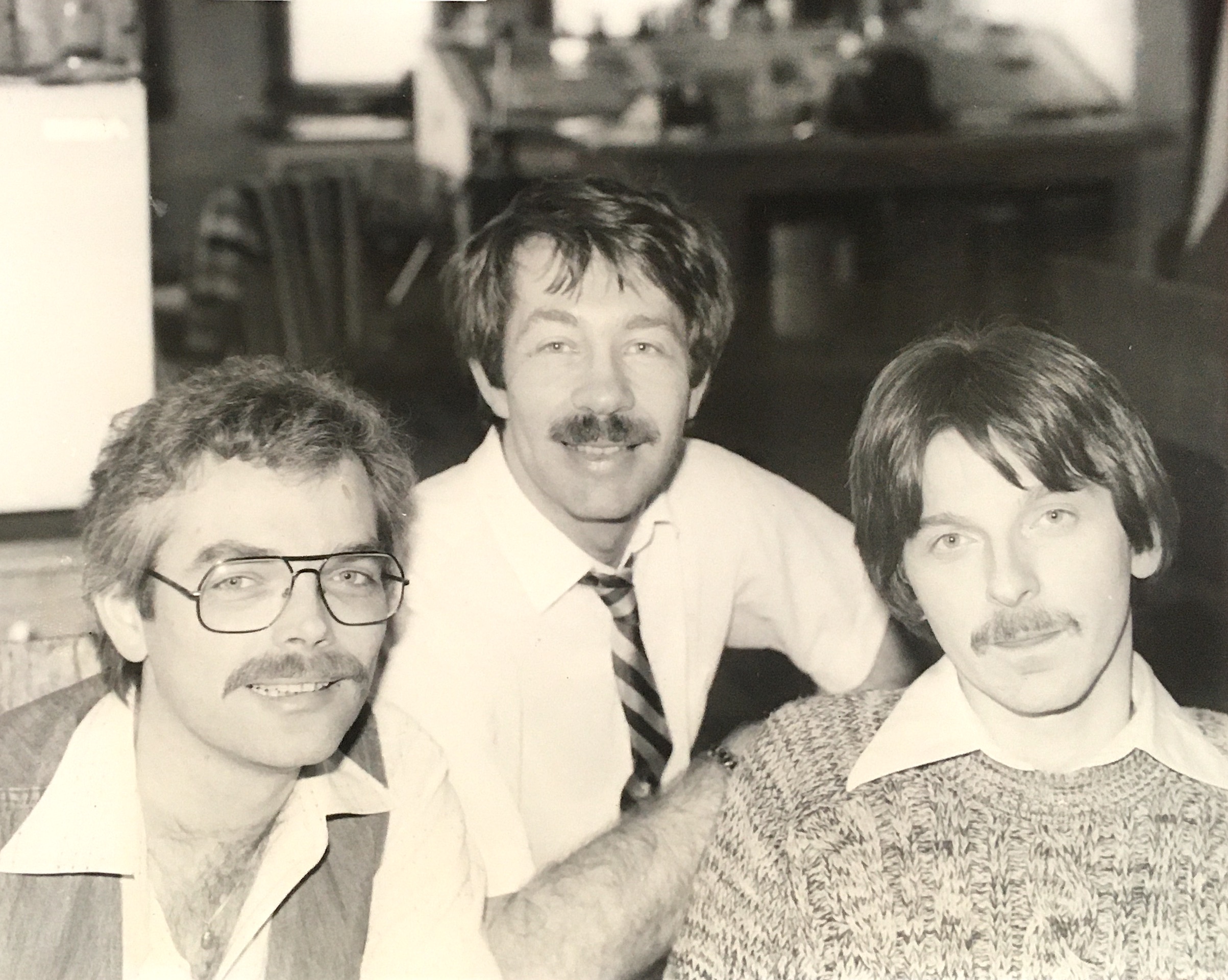

Credit: Ed Jackson

After that episode died down, and with the support of magazine editors who recognized his writing ability, Gerald became one of the most reliable mainstream journalists writing in the city, winning numerous National Magazine Awards. He became known as a superlative profile writer who adroitly captured people as diverse as architect Jack Diamond, mayoral candidate Rob Ford, singer Measha Brueggergosman, writer Tomson Highway and artist Kent Monkman. (All of his writing can be checked out on his website.)

In his later years, what gave Gerald the most joy was singing opera. He became involved in Toronto City Opera, a small community company, playing roles such as Rodolfo in La Bohème and Baron Zeta in The Merry Widow. A shameless ham, he was at his best mugging his way through the comic roles.

I recently asked Gerald if he wanted to write his own obituary. He demurred, saying that was best left to others. But he did offer one comment that was vintage Gerald: he opined that, whatever was written, he would likely have done a better job. And he was right.

I can’t imagine not having Gerald in my life. I will miss him terribly.

As will many others. Pink Triangle Press has asked friends from different periods of Gerald’s life to recall episodes that best capture their memories of him.

— Ed Jackson bounced from queer journalist to community health educator before finally retiring to obsess about queer history. He is the co-editor of two anthologies: Flaunting It!: A Decade of Gay Journalism from The Body Politic and Any Other Way: How Toronto Got Queer

Credit: The Body Politic

Xtra reached out to a number of friends and colleagues for their fondest memories of Hannon and what they see as his legacy. If you have a story about Hannon that you’d like to share, please join the Xtra Community to share your comment at the bottom of this collection of tributes.

“He spends the week in a pair of shocking pink shorts”

Gerald’s journalism and his activism were informed by his enormous curiosity and openness, and his willingness to withhold judgment until he had heard things out before formulating and articulating a thoughtful opinion. Oh, and did I mention his exquisitely refined love of silliness? As a result, he was both a fascinating friend and an ideal travel companion. From our many trips over many decades, a few images stand out.

1988: We’re in Jaipur, India, a few days into a two-month trip. We’re both still in culture shock, but Gerald nevertheless trustingly agrees to pay a gentleman a few rupees to drape a very large boa constrictor around his neck. Gerald beams; the snake looks away disdainfully. I nearly faint, so someone else has to take the photograph.

1999: We’ve arrived in Cozumel, on a week-long resort vacation with my extended family. Gerald opens his suitcase in our beachside cabin, and, with a look of puzzlement, says, “I only packed long, woollen pants.” (Because it’s January. And he was packing in Toronto.) He spends the week in a pair of shocking pink shorts purchased at the gift shop, much to the delight of my nieces and nephews, ages six to 12, who adore his oddness and the way he treats them like Real People. The shorts become his signature cottage-wear for at least a decade; the friendships with the kids last forever.

2014: I’ve convinced him to celebrate his 70th by doing the West Highland Way walk in Scotland with me. He’s starting, possibly, to feel some of the effects of his illness, or maybe it’s just old age. But he’s endlessly game and never complains, as long as the day’s exertions end in a hotel, a meal and one or more glasses of Scotch. One raw afternoon, we conquer the aptly named Devil’s Staircase and are headed downward to our reward in Lochleven, which we can see way off in the distance below us. Sadly, the path seems, perversely, to head up and in the opposite direction, and it has started to rain—hard. I snap a picture of Gerald standing despondently in the middle of said path, wet in that way that is much wetter than being just naked-wet. But a hotel, a meal and a glass of Scotch later, and he’s ready for more.

I am infinitely grateful for, and will always desperately miss, Gerald’s company on life’s journeys.

— Gerry Oxford is a former Torontonian who now divides his time between Haliburton and New York

“I’d come back and there’d be four or five letters he had written me”

I met Gerald in the change room at the downtown YMCA when I was 17. My friends and I were just talking about the pronunciation of “almond,” as stupid as it sounds. Gerald interjected about the correct pronunciation. English was a big thing for him because he was a writer. From then on, any time I saw him at the Y, I’d say hi and we’d start to have these two- or three-minute conversations. At the time I was starting to listen to classical music, and he had a whole lifetime of knowing about classical music and going to concerts, so we became friends from there.

I remember the first time we went to the Toronto Symphony Orchestra together because it was my first time experiencing an orchestra. It was The Planets by Gustav Holst and I was like, “Oh my God, this is amazing.” It was such a completely different experience for me.

He was such a very caring and supportive person. In the beginning, I had the problems of an 18-year-old, but he would treat them like they were of equal importance to him. He was never some adult who’d say, “Oh, you’re just a kid, your problems aren’t that big.” He always treated me like a grown-up, even though there was a 50-year age difference between us. As I got older, he’d let me use his apartment when he was out of town, and I’d go there and imagine what it would be like to have my own place.

We started writing letters to each other, which was amazing because it got me to read more, and helped improve my writing. He started out sending me clips of things he wrote to another friend, what books to read, stuff he recommended. But we shared other interests beyond music and music, and I’d write him back. I always looked forward to getting his letters. I’d be away for a while and I’d come back and there’d be four or five letters he had written me just waiting for me.

He’s given me everything, concerts and so many other life experiences. Sometimes I couldn’t believe I had a friend like him.

— Ali Syed, student of math, Toronto, in conversation with Xtra

Credit: Courtesy of Jane Farrow

“He sobbed. We all sobbed”

Generous. Gerald was unstinting in his generosity. He gave of his heart, his talents, his take on the world freely and beautifully.

I was on the receiving end of this lavishness on more than one occasion. In 2006, when presented with the opportunity to lead a neighbourhood walk for the first-ever Jane Jacobs walking tour initiative, I chose to feature early queer Toronto history.

I figured I could piece together the basic narrative and guide people through it, but how much cooler would it be to feature one of the guys who pretty much put the queer in queer Canadian history? To my astonishment, Gerald Hannon agreed to co-host the walk.

The May morning of the walk dawned crisp and blue. The crowd of 60 or so people, of all ages and orientations, gathered on the steps of the King Eddy hotel on King Street East. We set the scene of queer life in the 1950s. Men came to hear show tunes in the hotel piano bar accompanied by their female “beards.” Across the street at the Letros Tavern, crowds jammed into the basement for Halloween balls and drag shows featuring “bejeweled and begowned contestants.”

Gerald pointed up at a nondescript office building across the street. This is where, in 1979, the Toronto Seven staged a “Gay Sit-In” in Attorney General Roy McMurtry’s 18th-floor offices, demanding action on police and legal harassment. He wrote it up for The Body Politic back then, and had perfect recall of the events and people, relaying it in vivid detail interspersed with sparkling camp wit. His command of the material, and how to present it, made your spine tingle.

We invited people to share their own anecdotes and perspectives—and they had them. “I wore a tight pink sweater and once saw Noël Coward there.” “We danced with our lovers or dates, but when the buzzer rang we switched back to men with women so the cops wouldn’t bust us.” “I’d rent a practice room at Heintzman Pianos and cover the window with my jacket and make out for hours with my girlfriend.” Gerald never hogged the narrative; he inspired people to reflect on and be empowered by how they were woven into it.

The tour peaked at Yonge and Wellesley when Gerald stood on the same spot he did on that very cold evening of February 5, 1981, and relived what it felt like to participate in the birth of the modern queer Canadian movement. There, surrounded by hundreds of others protesting the bathhouse raids, chanting “No more shit,” he testified to how good it felt to push back and to know that our community had finally hit their limit. He sobbed. We all sobbed.

Twenty-five years had passed since that night, but Gerald brought it all back in Technicolor with his prodigious talents and generosity of spirit. Gerald was a show, not a tell, as they say in journalism. And having had a front-row seat for a few of those shows, he changed my life.

Within months of that walk with Gerald, I left my job as a producer and host at CBC Radio to take the Jane’s Walk movement from a local Toronto event to a global phenomenon offering volunteer-led neighbourhood walks in hundreds of cities around the world. We should all be so lucky to walk, and sob, in the streets with a man like Gerald.

— Jane Farrow is a writer and principal of Dept of Words & Deeds

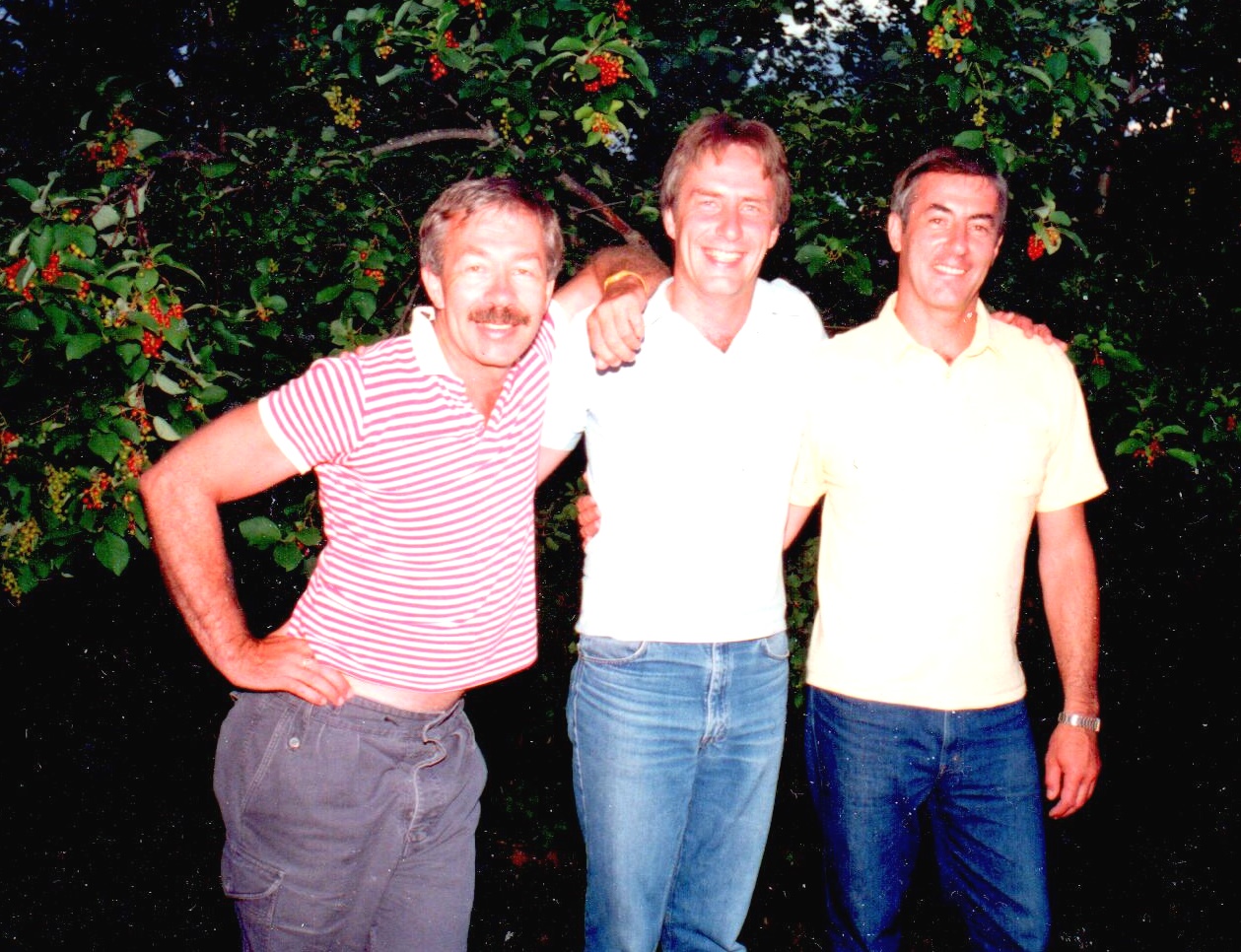

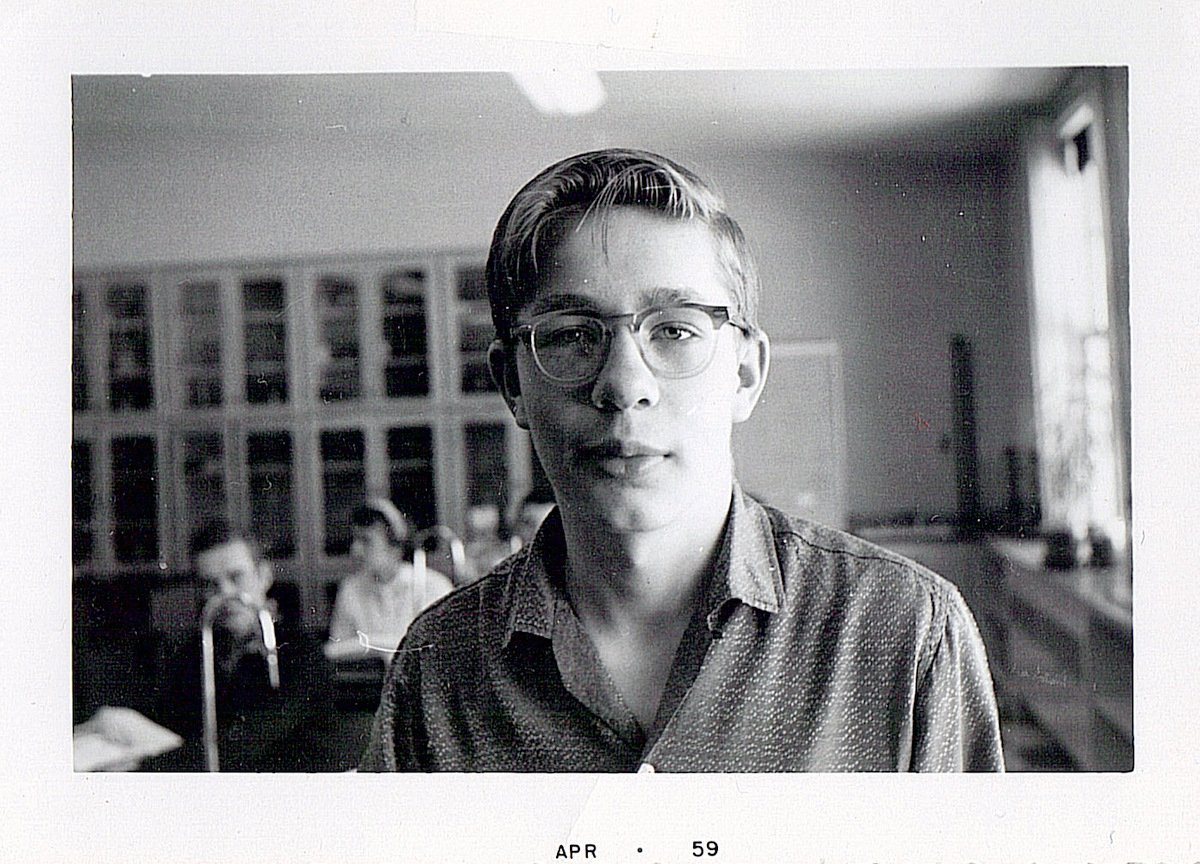

Credit: Courtesy of the Hannon family

“Gerald was there to be Mickey Rooney, I got to be Judy Garland”

Moving to Toronto from Long Island, New York, in 2000 meant for me the end of a treasured Met subscription, but my husband noticed a Toronto District School Board continuing-education course in “opera chorus.” I viewed myself as a consumer of opera rather than a practitioner, but I had sung in various choirs since high school, so I cautiously signed up in the fall of 2001, the same time Gerald joined.

Gratifyingly, I found that the Toronto Opera Repertoire (TOR), under the unapologetically old-school direction of Giuseppe Macina, mounted public performances of fully staged operas. The venue was a grubby former high school auditorium, but the sets were real and the costumes were top-of-the-line Malabar! The demanding solo parts required auditions, but the chorus was open to anyone who paid tuition, showed up and quickly got “off book.” I found these ambitious goals congenial and I jumped right in.

Gerald, a soloist, shared my enthusiasm for this amateur departure from mundane everyday life. We quickly became friends and were drawn into the administration of TOR, he as president and me as secretary. Our complementary skill sets and concordant attitudes made for a harmonious relationship. For example, my professional experience as a data analyst made me the obvious choice to measure the cast members for their costumes; Gerald’s brilliance with words made him the one to write grant proposals and translate libretti into witty projected surtitles (with the occasional reference to local issues). And he shone brightly in his solo roles, especially the difficult “patter roles.”

We cemented our bond with a long-running email conversation. Almost daily for 10 years, we touched on topics ranging from dull administrivia to more provocative topics such as the diverse personalities of our company. We admired the courage of singers who were handicapped by Asperger’s or a stutter. Other quirky cast members induced snarkier reflections.

One summer, Gerald took the train to western Colorado to sing with me in the chorus of Pagliacci. The soloists were professionals—we decided it was the closest we’d ever get to singing at the Met.

Our ambitious version of TOR ran into headwinds: principals and audiences aged, funding became elusive and Gerald and I stepped back as a new version of TOR evolved. Of course, there were rough spots, but they have been smoothed by grateful memories. Looking back, our TOR years summon up those idyllic pre-war MGM musicals in which the leads decide to “put on a show in the barn.” And because Gerald was there to be Mickey Rooney, I got to be Judy Garland.

— Barbara Thomson is a retired statistician and official FOG

“It was the first time he had ever been paid for his writing”

In April 1985, Tarragon Theatre commissioned me to create a large-scale performance installation for their first Spring Arts Fair. Wagner’s Rinse Cycle linked a live Metropolitan Opera broadcast of Parsifal to stylized tasks of washing, drying and ironing in real-time. These chores continued alongside a slideshow of images, portable radios suspended from pipes, and readings.

For the latter, I had solicited contributions from several personalities on the theme of opera and laundry. Gerald’s told of how as a youth he had to secretly listen to Met broadcasts in his basement, on a dusty tube radio beside the family wringer-washer. This was read in the five-hour show as part of our own Radio Opera Quiz. The following week, from funds awarded for the purpose, I sent him a small cheque for his effort. Gerald, an early member of The Body Politic and a prize-winning investigative reporter, later astonished me upon revealing that it was the first time he had ever been paid for his writing.

My further connection with Gerald and opera would wait another 18 years, when the phone rang and he asked me to join him in a production of La Bohème as Head Waiter in Act Two. This was the start of my nearly 20 years of singing in chorus and non-singing comic parts with Toronto City Opera, frequently sharing scenes with Gerald onstage.

— David Roche is a Toronto performance artist and singer who has known Hannon since the early days of 1970s gay lib

Credit: Courtesy of The ArQuives

“Coming out, telling the truth, became the radical ethical imperative”

Gerald Hannon didn’t have a political bone in his body. That may seem to be an odd assertion to make about someone whose life was immersed in a series of political controversies, from intergenerational sex to sex work. But politics involves strategy, tactics, calculation, compromise, identifying allies, sometimes subterfuge, all modes of operation foreign to Gerald. I once described him as guileless; that is, innocent, without deception. Gerald always said exactly what he thought to be true, without much consideration of any possible consequences because telling the truth was just obviously the right thing to do.

I think, like many of our generation, Gerald was shaped by the ethic of coming out. Queer, small-town boys growing up in the 1950s learned very quickly to keep their own council. But then gay liberation happened and overthrew all that. Coming out, telling the truth, became the radical ethical imperative. Gerald was a convert. In an early Body Politic, he wrote, “Throat-ramming must become the social extension of our public struggle for civil rights…. It means never appearing in public with another gay person (or persons) unless it will be obvious that you are gay people.… It means never appearing in public alone unless it is as obvious as you can make it that you are a gay person.”

It was this radical honesty, the imperative of always telling the truth about sexuality, that shaped Gerald’s work. He was not a pedophile himself, but if sexual repression was harmful, and young people were sexually repressed, then writing about youth having sex with each other or with adults was the ethical thing to do. He expressed that “truth” in a series of articles that culminated in “Men Loving Boys Loving Men,” and criminal charges against TBP that dragged on for years.

Later, when he was teaching journalism at Ryerson [now Toronto Metropolitan University] and supplementing his income as a sex worker, why wouldn’t that be a truth he would share? That got him excoriated in the media and eventually fired.

Gerald wasn’t one of those people who delighted in telling others “hard” truths that could wound. He was gentle and kind, but just could not understand what all the fuss was about sex, or why anybody considered talking about it such a big deal.

In the midst of trying to build a political movement, with all the strategy, tactics, calculation, compromise, alliances and sometimes subterfuge involved, Gerald’s guilelessness could be infuriating. But for Gerald, the analysis was straightforward, and the principle of speaking one’s truth was never to be abandoned for the sake of political expediency.

— Tim McCaskell is a long-time gay activist and writer, and was a member of The Body Politic collective for more than a decade

“I twirled him a couple of times and he gamely followed”

“Two, Four, Six, Eight, Gay is just as good as Straight. Gay rights now!” These were just a few of the chants of the early gay rights movement. Shouting them, at the forefront, was Gerald Hannon.

When I first met Gerald, he didn’t have a mustache. In fact, I was the one with a downy shadow. I knew very well who he was. His reputation preceded him. As a teenager growing up in Winnipeg, I would sneak-read The Body Politic at the socialist bookstore, Liberation Books. Gerald was both lauded and vilified for his politics and writing. So, the prospect of meeting him made me nervous, even hesitant, but I was also curious and excited.

When we finally met, I was surprised, disappointed even, that this gentle, soft-spoken man was the notorious Gerald Hannon. He didn’t have horns, as painted by the right-wing media, nor did he breathe fire. And this is exactly what I came to love about him—his ability to be quietly, yet fully, present, and his faculty for observation and non-judgment.

In the early days of getting to know him, I attended one of Gerry Oxford’s famous Coach House parties. Climbing the sweeping staircase to the second floor recalled the grandest Paris apartments, and I imagined entering the salon of 1920s lesbians Natalie Barney and Renée Vivian. Instead, I encountered a room brimming with gay men, with not a lesbian in sight. Music played, but unlike every dyke party I had ever attended, there was no dancing. These were The Body Politic intellectuals.

Later that evening I held out my hand to Gerald, and we started to dance, he clumsily at first.

“One, two, three, one, two, three,” I whispered while deftly taking the lead. I twirled him a couple of times and he gamely followed. And here we were, a former lesbian separatist dancing with a gay male liberationist. “Two, four, six, eight …” Years of friendship ensued.

In April, I saw Gerald one last time. Maya and I spent a tender hour with him. As we were leaving, I was tempted to hold out my hand and twirl him one more time. But he was too fragile. Instead, I gave him the best hug possible; one learned from every Butch Dyke, Faggot, Queen, Radical Fairy, Queer, Lipstick Lesbian, Trans, Two-Spirit person who ever hugged me.

The kind that says, for this one moment I will never let you go.

— Justine Pimlott is a gender queer filmmaker, activist and sometimes tap dancer

Credit: James Thomson

“After a swanky dinner, Herbie pulled out his dick and slapped it on the table”

It is hard to imagine how my life would have turned out differently had I not met Gerald Hannon. He opened not only the world of gay people to me, but also opera. Gerald was my first boyfriend; at the time he was the most famous homosexual in Canada, and even still today is the only person I have ever met who actually saw Sputnik.

Gerald and I met in 1982, at a party at Michael Lynch’s house, where I was James Fraser’s date. This was the pre-AIDS era where at parties The Body Politic people would nod and seriously opine, “Promiscuity really is the glue that holds the gay community together.” I said “Oh, who is that, he’s cute.” James then introduced me to Gerald. It turned out I really liked Gerald. In fact, he was quite fun.

At the beginning I was still in architect school; things were tight, but he wasn’t any wealthier—full-time at Pink Triangle Press was paying $8K/year—so, it worked. Gerald, who was once slightly frightened by the Royal York Hotel—emerging from Union Station the first time, it was the biggest thing he had ever seen—got a crash course in architecture, and I, a crash course in the wonders of being gay, by masters of the craft, his circle of friends, most of whom were somehow connected to The Body Politic.

One time, Gerald and I went to New York City for a long weekend. We stayed with his friend Herb Spiers, who lived in a loft near Gramercy Park. He had the whole second floor of an old commercial building that his boyfriend Ray Gray had purchased for a song when New York almost went bankrupt in the mid-1970s. Ray’s space was the whole top floor of the building (and the roof), which we visited using a tiny elevator that only stopped at two and seven. It was crazy awesome, also exactly what you would want.

Ray was an interior designer from Hollywood, California. Handsome. His loft, fully marbleized, was adorned with big Babylonian movie flats and large paintings. After a swanky dinner, Herbie pulled out his dick and slapped it on the table; it was his way of saying it was time to go to the Saint, an unbelievably fabulous private gay club inserted into an old theatre. For a brief moment there, I got a glimpse of the A-list New York gay life I had only ever read about, or heard about from Gerald, in what would turn out to be the last moments before it all went bad. Ray would be dead in a year.

Gerald took me to the Anvil, the Everard, the St. Mark’s, the Mineshaft. He thought I should see these places, so many stories were attached to them. But also he took me to a party at the home of the writer Jonathan Katz, where we both met the gay hero Harry Hay, founder of the Mattachine Society, the first gay rights organization. Both publicly and later privately, Harry was generous with praise for Gerald’s writing and activism; that is where I really got the sense of the importance of Gerald. Without Gerald, not just our city, but all Canada, would have been less free. He opened up the law, throat-rammed it until it hurt, turned himself into the Antichrist in the eyes of some, while carving out a larger space in our society for LGBTQ folk, who were always there anyways (also the whores). If they knew Gerald as I do, they would know his gentle kindness, his passion, his humour and love. Being with him makes me happy and I will miss him so.

— Chris Lea served as the first openly gay leader of a Canadian political party (Green Party of Canada) and was on the board of the Toronto City Opera with Gerald Hannon

Credit: Andrea Houston

“His bitchiness was entirely understandable”

The first time I ever spoke with Gerald Hannon, I got a journalism lesson. “I wouldn’t allow any of my students to conduct an interview like this,” he said, reprimanding me.

It was a pretty rich irony, given that Hannon had just been cancelled from his part-time Ryerson teaching gig after the Toronto Sun put him on their cover, with the quintessential Sunny headline: “Ryerson Prof: I’m a Hooker.”

I called him up to try to sort out the various newspaper stories, some critical of him, others defensive, some on the fence. His bitchiness was entirely understandable: many writers rely on teaching gigs to supplement their income, and Hannon had just lost his, for reasons that were spurious, at best (memo to the university formerly known as Ryerson: might be time for an official apology to Hannon). On top of that, Hannon was getting mysterious calls from a psycho crank caller—approximately 20 per day—from a number Bell Canada told him didn’t exist.

The next time I met up with Hannon was about a year later when we were both on a panel about queer sexuality and scandal in the media. I had profiled Ashley MacIsaac for the American gay and lesbian magazine The Advocate, and had chosen not to include quotes from the famous fiddler regarding his appetite for water sports or teenage boyfriends. Maclean’s magazine learned of the profile before it appeared, and assumed we would run with the dirt, so they pulled him off their annual Honour Roll list. Many felt I’d done the right thing by protecting MacIsaac. Hannon wasn’t having it. “You failed,” he said. “You could have worked to explain his sexual activities, helping readers to understand them, rather than taking them out of the article altogether.”

It seems I was getting a big fat F from Professor Hannon, and not the kind of F he was famous for giving. He laughed with me at the post-panel cocktail party, when I asked if there was any remedial work I could do to get back in his good books.

Hannon’s honesty, like many of his other traits, was part of what made him an utterly brilliant journalist. He never worried about hurting feelings or offending. It matched his bravery, his wit and his incredible ability to craft sentences and paragraphs.

Losing Hannon and his talents is devastating. My only comforts are that he was able to choose a dignified exit, and that he managed to finish his memoirs before checking out. They should be required reading for every journalism student.

— Matthew Hays is a Montreal-based journalist and author who teaches courses in film studies and journalism at Marianopolis College and Concordia University. He has contributed to Xtra since 1991

“He soon was composing new works using notation software on his computer”

Gerald was in my life from as early as I remember. He was there taking pictures at events my dad took me along to, dinners and drag parties… and in the last days of my dad’s life. He was my auntie—I grew up with him always around. He was sweet and a little awkward, and even to my child’s sense of the world, he had his head in the clouds. As I grew up and began reading his journalism, especially his long profiles of famous Canadians, I was shocked at his astute observations and pointed opinions, which belied that childhood impression.

When I was a tween and Gerald was middle-aged, I sat at a dinner party as he explained in his usual half-reluctant, almost doddering way that he was learning to play piano and read music. He soon was composing new works using notation software on his computer that he’d also taught himself to use. At 14, having failed utterly to please my dad and learn to play the piano—and convinced I was out of time to ever learn an instrument—this was a revelation. I have not shied away from learning new things as I’ve aged, and always remind myself of Gerald’s late-coming to music when I feel fear. This year, at 50, I decided to learn trope—the cantillation system for chanting Torah—and in June will do so in front of my synagogue for the first time. Thank you, Gerald.

When I was 15, Gerald interviewed me for an article in The Globe and Mail, in which we talked about my growing up in the gay community, and his mother’s lesbian life. It was the first time I committed to print my evolving identity as “erotically straight and culturally gay.” This evolved over the next decade, as I helped build a movement of kids with LGBTQ parents, into the word “queerspawn,” which I coined in the early 1990s, and is now the preferred descriptor for many thousands of folks with queer parents. Gerald himself eventually described himself to me as “probably the oldest queerspawn you know, Stef.” Thank you, Gerald.

The obituary Gerald wrote for my dad—who died when I was 19—remains one of the sources I turn to when I miss my dad [Michael Lynch, a university professor, journalist and activist who taught the first gay studies course at a Canadian university]. In its precision and unflinching queerness, its avoidance of the worst tropes of obits, especially AIDS obits and unmaudlin elegy, Gerald captured and kept alive an essence of him that felt true then, and still feels so. Thank you, Gerald.

—Stefan Lynch was raised in Toronto’s gay community in the 1970s and ’80s, and was the first director of COLAGE, the international organization for people with LGBTQ+ parents

Credit: Maurice Vellekoop/StoryCorps

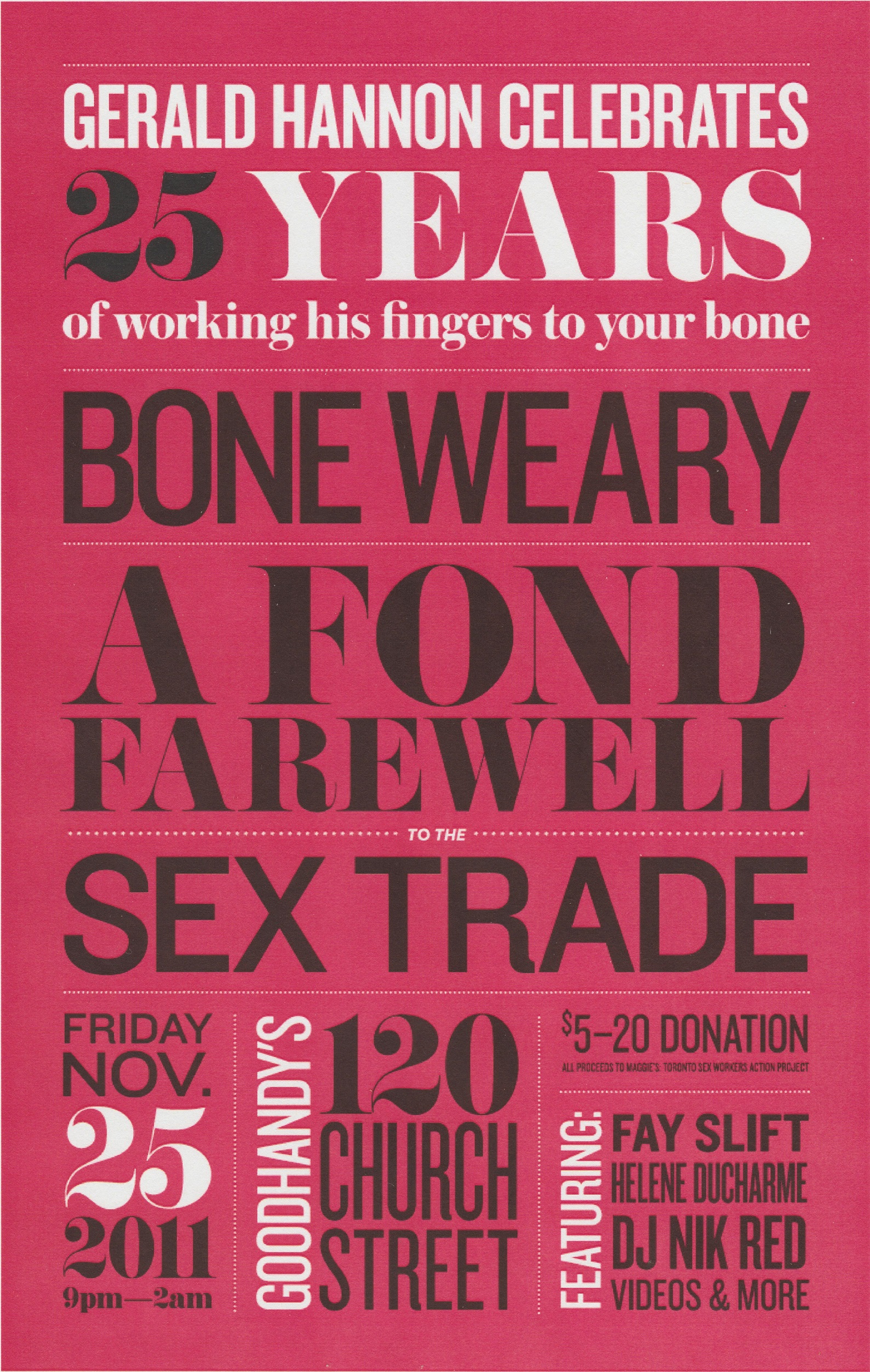

“Curtains had to be pulled in case there was a sniper”

Gerald Hannon never missed an opportunity to be a mentor to young journalists, including myself.

One of my fondest memories of Gerald is of covering a party to celebrate his retirement from sex work in 2011. The event was at the club formerly known as Goodhandy’s, and doubled as a fundraiser for Maggie’s: Toronto Sex Workers Action Project. At the time, Hannon was watching the Ontario courts closely, because the previous year Justice Susan Himel had struck down three key anti-prostitution laws.

Today, sex work is still not a protected right, nor is it decriminalized.

At the party, Gerald gave me advice that I later asked him to expand on, because I felt it needed to be shared with other young people in journalism: that sex work can be a very lucrative side gig if writing isn’t paying the bills (as it so often doesn’t).

Gerald described himself as a “satisfier of human need, whatever that need may be,” in an essay/love letter to sex work, which he read at the party. “Prostitution has been the splendid discovery of my middle years,” he said.

“Fifteen years ago, I lost a teaching job for honesty and a complete lack of shame.”

In 1995, Gerald found himself at the centre of a media circus after the Toronto Sun revealed that he worked in the sex trade. “Ryerson Prof: I’m a Hooker,” screamed the front-page headline.

At the event, Gerald talked candidly about what it was like to go through that period, and how everything changed the day the newspaper hit newsstands. The backlash was immediate. Its eruption echoed earlier controversies. The university had already investigated him because of his 1977 Body Politic article “Men Loving Boys Loving Men.” “Ryerson had completed an investigation and determined I was not teaching pedophilia, I was teaching journalism,” he said. That investigation, of course, had followed the prolonged legal battle about the article.

He described how those controversies impacted his ability to teach. “There were death threats. That was the worst. I had to be escorted to the class by security. Curtains had to be pulled in case there was a sniper. Students had to be allowed in one by one. Once inside, the door had to be locked to the classroom with a security guard standing outside.”

Years later, I’m now an instructor in the School of Journalism at the same institution, Toronto Metropolitan University (formerly Ryerson). And in 2018, I was so lucky to have Gerald speak to the students in my Queer Media class, who learn all about how journalists like Gerald helped pave the way for them.

It was such a beautiful and powerful full-circle moment for Gerald, returning to talk to a room full of future journalists about system-changing journalism at the same school that fired him all those years ago.

— Andrea Houston is managing editor of Ricochet Media and instructor at Toronto Metropolitan University School of Journalism

“Gerald was a champion of the bon mot and the double entendre”

It was his laugh. Gerald’s Hannon’s laugh, somewhere between a chortle and a snigger, started somewhere deep within, and bubbled up through his shuddering torso and out quivering nostrils and lips. He laughed often, which is partly what made him so endearing. Coming out into the gay community in mid-1970s, Toronto was scary for a Chinese kid raised Catholic in the Caribbean. This was a time when you could count the number of non-white faces in a crowded gay bar on one hand. The gay movement was even less diverse, and therefore more intimidating, not because people were unfriendly; it was just so unfamiliar. Gerald’s joviality was a welcome mat.

What I recall most volunteering at The Body Politic offices is the constant trade in witticisms. Gerald was a champion of the bon mot and the double entendre. But his writing also possesses that other kind of wit: keen intelligence. It’s courageous, too, in its fearless confrontation of social convention. When Gerald wrote about being a prostitute, he paid the price with his teaching job, but his case no doubt contributed to opening up conversations about sex work.

He was one of Canada’s original gay activists, from the era when gay liberation was linked to sexual liberation. Gerald was the best kind of relic.

— Richard Fung is an artist and writer born in Trinidad and based in Toronto

Credit: Courtesy of The ArQuives

“You could envision him stepping off a curb in front of a speeding truck”

When I met Gerald Hannon in the fall of 1972, he was not a striking figure. He was somewhat shabbily dressed, had thick lips, a bulbous nose and small eyes that were sadly reduced by thick spectacles. More than myopic, he seemed inner-directed, oblivious to the passing world. You could envision him stepping off a curb in front of a speeding truck.

I had just arrived in Toronto from Saskatoon and met Gerry and Ed Jackson at a meeting. I figured they were lovers based on small signs of intimacy—a question from Ed about where Gerry had left his jacket, perhaps, or whether he had streetcar fare.

Eddie was protective of Gerry, but they were just friends: it was Ed and I who became lovers. By the next summer we were living together in a household that included Gerry, his new lover Robert Trow, and Herb Spiers. Four of us were members of The Body Politic collective, and we moved the newspaper’s offices into our basement. We lived together for the next six years.

Robert took on the day-to-day “mothering”—making sure that Gerry was fed, dressed and on time—but Ed, the rest of us in the household, and many other friends continued to keep a protective eye on him.

Unprepossessing in appearance, Gerry was another man when he spoke. His voice was deep, rich and, yes, fruity. Witty, insightful, self-assured, he chatted as though he were reading from a beautifully crafted script. Yet he was a careful listener, and his conversation was quick and responsive: scripted but at lightning speed. Small wonder that his written work was so fine.

Over time he became The Body Politic’s star writer. Brilliant and audacious, he also had a blind spot that meant he couldn’t quite see why lesbian readers would object to a proposed article, “In Praise of Big Cocks.” And he foresaw no problem with writing an account of the love between men and boys.

Inevitably, the speeding truck arrived. In 1977, Gerry, along with TBP board collective members Ed Jackson and Ken Popert, were arrested on obscenity charges related to the publication of “Men Loving Boys Loving Men.” They were dragged through the courts repeatedly over the next six years, until the Crown finally accepted their acquittal.

As author of the piece, Gerry achieved notoriety and his self-appointed protectors feared that he would be forever blacklisted and unemployable. One friend made Gerry the beneficiary of his life insurance policy and was subsequently taken by HIV/AIDS. The bequest allowed Gerry to buy his condo. Another left Gerry a large chunk of his estate, which helped ensure Gerry’s comfortable retirement. Some of us hired him for freelance writing jobs after The Body Politic ceased publishing. Others championed his career in journalism.

Those of us who protected Gerry did so not just because he was lovable and vulnerable, but because you knew he was important. That perception was justified when he fought the law and won. The “Men Loving Boys Loving Men” case did not change public opinion about man/boy relationships. But it did help establish gay people as a self-defined class of people with a forum in which we examined our own lives, discussed our own interests and developed our own mores: a community with a legitimate claim to freedom of the press.

Gerry’s legal wins were satisfying for his protectors, but the real joy came from watching as Gerry’s writing talent prevailed, and he went on to reap journalism awards, stir up fresh controversy and rebuild his notoriety. That was his gift—he made winners of us all.

— Merv Walker is a Saskatchewan-born retired writer and gay activist

Credit: Courtesy of Ed Jackson

“My first major ‘straight’ assignment”

By 1988, Gerald was hardly a neophyte writer. His byline, after all, had been appearing since 1972 in the pioneering and influential The Body Politic. It’s not true to say that as a writer he was little known outside of the gay community, given the long-running drama around “Men Loving Boys Loving Men.” But he hadn’t appeared widely outside the gay press. What happened in November 1988 was “Gay After AIDS,” a feature for Toronto Life. Gerald called it “my first major ‘straight’ assignment.”

His second “straight” piece was a profile of the Globe and Mail’s cerebral art critic, also for TL. Here’s how it opens: “John Bentley Mays is not a drag queen…. But I can tell you what he looks like in a dress.” It was a silver award winner at that year’s magazine awards. A look at Gerald’s website suggests what followed. There, you can read 250 articles—far from everything he’s written—most for mainstream publications that range from Cottage Life and Chatelaine to the Globe and Canadian Business, with a little porn thrown in. But Toronto Life was his biggest market; between that first piece and 2014, when he was winding down his freelancing career, Gerald wrote 62 articles for the magazine, 52 of them profiles. A lot were National Magazine Award winners.

Take a look at his site and you’ll see why. “He’s a contender because he is a master of retail politics. He is the Walmart of politicians. Price point is everything.” That’s from Gerald’s 2010 piece on Rob Ford, a gold award winner. Or this: “I see now that one thing I loved about my mother’s cooking was its predictability…. Food, perhaps because it was scarce and unvarying, always seemed to tremble with the potential for good or ill.” Another gold award winner, “The Alchemy of Pork Fat.”

On Shinan Govani: “It may be, for a gossip columnist, that having a life, with all its wounds and bliss and gaucheries, would be perilous…. So you float through the land of smiles, night after brilliant night, till the purring all around finally stops, the Cheshire smiles begin to fade and your eyes adjust and you’re on the street now, 4 a.m., and there’s your cab, and there, somewhere up ahead, is your apartment.”

Gerald, my old friend, will be remembered as many things: activist and icon, shit disturber, sex worker, great journalism instructor. What I’ll think of the most are his luminous words on the page.

— Lynn Cunningham is a freelance editor and Toronto Metropolitan University J-school associate professor emerita

“In a world full of obvious lies, it was riveting, slightly scary truth-telling—and I needed it”

I met Gerald Hannon through Toronto Life magazine. He had been writing for the magazine for years by the time I joined the staff. His profiles were smart, full of originality and, as Toronto Life’s longtime editor Sarah Fulford said, written for the reader, not for the profile subject. Sometimes you fall for a profile subject. He might have done so, but that never affected the writing. His best pieces—profiles of Jack Diamond and Zena Cherry, of Measha Brueggergosman and Edward Burtynsky—often won National Magazine Awards. They were often as good as magazine writing can get. He was equally good on men and women.

As a junior editor at Toronto Life, I asked him if he would write a short double profile for my section, the front of the magazine, on one of each. I wanted him to write about the then First Couple of the Left, Jack Layton and Olivia Chow. Doing two people justice in a small space needed that extra level of deftness I knew he could manage. When firming the assignment up, I told him that we had a special Gerald rate for these pieces. “Oh,” he said in that nice melodic voice of his. “Is that rate higher or lower than the regular rate?”

As a gay editor and writer, I particularly admired his activist coverage of the bathhouse raids for the predecessor to this publication and his piece (also for Toronto Life) about the AIDS crisis, written early on. In that piece, he wrote, in his raunchy and literate way, about the range of sexual preferences and practices in his set. Things were happening indoors, outdoors, everywhere. I read it in one sitting—it was just a year or so before I’d come out. In a world full of obvious lies, it was riveting, slightly scary truth-telling—and I needed it. I am grateful to Gerald and his cohort for opening various doors that so many of us then walked through. The talent and bravery, the humour and drive toward excellence in the man.

— Alec Scott is a Toronto-based writer and editor

“You won’t believe it. I’ve thought of an idea!”

One evening, in the mid-summer of 1997, Gerald Hannon and I were sitting at his place, sipping Glenlivet, one of his favourite single malts. We had likely eaten, likely ordered in, likely Thai, since the best spot for delivery was a Thai restaurant in the Gay Village. He had recently had another wonderful, perceptive profile published, this one in Canadian Art on artist Attila Richard Lukacs, who was a perfect subject for Gerald, being an edgy painter of high and low culture.

Gerald described him this way: “He’s not handsome (imagine the Pillsbury Dough Boy, fresh out of jail, slim now, but still soft, still white, still smooth, with a stylized dagger tattooed on his right calf), but he’s sexy.”

“You were assigned to write that story, weren’t you, Gerald?”

“Yes.”

“And you never think of story ideas yourself, do you?”

“No.”

“Why is that?”

Gerald looked at me with his characteristically doleful expression. “I don’t know, Davey. They just don’t come to me.”

In the business of freelance writing, it is rare to find someone so advanced in their career, and as successful as Gerald, who never produces story ideas. They are the currency of exchange between writers and editors. There is an expectation that every freelance writer generates ideas. Among other things, they enable a writer to avoid being assigned stories that are lame, or of no interest to the writer.

“Do you ever wish you could come up with your own ideas, Gerald?”

“No, Davey.”

“Why is that …?”

And so on.

Sitting in my office one morning weeks (or was it months?) later, my phone rang.

“Davey,” said Gerald, sounding like a small boy who had discovered a shiny new bike on Christmas morning. “You won’t believe it. I’ve thought of an idea!”

I wish I had a good resolution to this story, but I don’t remember what the idea was, whether it had any promise, whether he ever pursued it or whether it was ever published. Which probably suggests it wasn’t a winner.

Was there ever a more brilliant writer with so few story ideas of his own? In the end, it didn’t matter because his observations saw through any artifice, and his insights into the nature of each assigned profile subject were so penetrating that he captured more of their essence than even the subjects themselves understood. As a writer, he had an intelligence and inventiveness that did everything … except generate story ideas.

— David Hayes is a Toronto-based freelance journalist

“Most of my artistic projects were dreamed of in response to what Gerald and I were talking about”

I met Gerald in the winter of 1996. He had come to Trent University to do a talk about the Ryerson scandal. It was still raging so he couldn’t really talk about it, so instead discussed freedom of thought, questioning our assumptions about the world, and activism.

For some reason they put the talk in a very small room. Professors occupied all the chairs. Myself and the few other students who had come sat on cushions at the back. It felt like one of the most poignant talks I had been to, moving away from the theoretical philosophy and cultural theory I was learning, to the practicalities of a life.

We adjourned to a university lounge for wine and cheese. I boldly walked up to Gerald and told him I had enjoyed his talk a lot. There were a lot of people around him. He shook my hand, though I’m not sure if he asked my name. Gerald doesn’t remember this at all.

I really met Gerald in 2000 when I interviewed him for a magazine some friends and I were starting about queer life, writing, work—in fact, I can’t really remember what it was about. I had never interviewed someone before, so we met for dinner at Gerald’s favourite restaurant. I had a tape recorder and took notes. (By the way, Gerald’s favourite restaurants were usually empty and very quiet; we used to joke about how him frequenting a place was probably the death knell of the establishment.) I don’t think I wrote a good profile, but what started was a bond.

I have been asked what Gerald meant to me. I have come up with “muse.” Most of my artistic projects were dreamed of in conversation with or in response to what Gerald and I were talking about. Trying to see the world through his eyes opened up a world for me.

I have also been asked what memory I have of Gerald or when I was closest with him. I feel horrible because I don’t have one. But I’ve never felt far from him. We saw each other weekly, if not more, for 22 years. He will be with me the rest of my life, and I hope to share his wisdom and insights with others. My conversations with him will continue.

— Peter Kingstone is an artist in Toronto

Credit: Ryan Crouchman

“Who could read those words and not wish to have written them?”

Whether a bewildered naïf or a sly provocateur, Gerald often gave the impression of someone hovering somewhere just beyond the mundane details of life.

This persistent extraterrestrial aura, this apparent ignorance of earthly consequences, perhaps contributed to his distinctive prose style, and certainly to his habit of writing the original and the unexpected. And, in some cases, the unwelcome.

We both wrote political pieces for TBP throughout its 15 years, but I felt that I was writing billboards while he was setting off fireworks. Referring to the gay activists of the 1970s, he wrote that we “grabbed today and shook it until tomorrow fell out of its pocket.” Who could read those words and not wish to have written them?

But he was a challenging co-worker and occasionally left me wondering whether I was the target of a droll, never-ending leg-pull or perhaps had wandered into an undiscovered Oscar Wilde script.

For example …

In the early 1980s, having been tasked with the purchase of a suitable phone system for TBP’s new office on Wolseley Street, Gerald bought a product festooned with features ill-matched to our needs. When questioned, he explained that he found comparison-shopping too confusing, and so bought the system because he liked the colour.

Some years later, I sweated for many days to construct a budget allowing us to thread our way through the financial crisis that led to the closure of TBP, but the preservation of Xtra and our organization. As I finished presenting it, Gerald blandly turned to his desk, rummaged around and produced a wad of paper which, unfolded, turned out to be an overdue bill for thousands that made confetti of my plan. After receiving it some time before, he said, he had folded it up and tucked it behind his desk caddy because he hadn’t wanted to think about it.

See what I mean?

And I vividly remember another collective member, in a moment of frenzied frustration, picking up the in-basket from his desk and hurling it across the room at Gerald in the wake of a particularly inflammatory Hannonism. (He missed.) So, it wasn’t just me.

Gerald sometimes modestly remarked that writing was his only talent.

An obsessive and anxious rewriter myself, I once asked him how many drafts and revisions he went through to produce his come-read-me pieces. His reply, offered in a deflatingly offhand fashion: “Oh, I never do drafts; I compose the whole thing in my head and just write it down when it’s done.”

It may have been then that I realized that my future lay in publishing, not in writing. I could never learn to be a Gerald Hannon. Because being Gerald Hannon was a talent, not a skill.

— Ken Popert, Xtra’s former publisher, has been involved with Pink Triangle Press since 1973 when he helped establish the news department of The Body Politic

Credit: Ed Jackson

“As the evening wore on, we longed for the opera lesson”

A snapshot. The last time I saw Gerald. JP and I came to say goodbye, although we never uttered those words. Ed was arranging these visits—a farewell tour of sorts.

As we sat, Gerald hovered precariously above his chair, then dropped into his seat, his body frail, almost weightless. We talked, touching lightly on everything from his activism and sex work, to how we met. Gerald was in fine form, managing several quick-witted bon mots.

We recalled an evening, many years ago, in which Gerald had invited a small group for dinner and opera appreciation. As it turned out, the evening became something else entirely. One of his “gentleman callers” unexpectedly showed up, and Gerald, being Gerald, asked if we were okay with a change of plan. After some discussion, we agreed, but as the evening wore on, we longed for the opera lesson.

Gerald later wrote about it, describing the pseudonymous “Steve” as “an obsessive exhibitionist who likes people of both sexes to tell him how fabulous his cock is and then to jerk him off.” (Reader, we declined.) He also mischievously portrayed JP as a “devout lesbian” who “thought (Steve’s) cock rather small, though it turned out the only others she’d seen were in gay male porn.”

It was the kind of evening that gets better with retelling. Now, here we were, decades later, sharing a good laugh about it. Across from us sat Ed, who seemed pleased the visit was going so well. How do you say goodbye to someone on the brink of choosing his own death? These were precious days—at once troubling, profound and life-affirming—and we were navigating unknown territory as best we could.

As we talked, Gerald began to flag. “Are you okay?” I asked. “No, I’m not,” he said, but he wanted us to stay. Later, I asked if I could take a photo. “You look so beautiful,” I said, “and the light …” And he was beautiful, the afternoon light caressing his face just so. Gerald gazed directly into the camera, but he was clearly far away—here but not here.

A moment forever captured in a photograph. A memory that may or may not get better with retelling.

— Maya Gallus is a documentary filmmaker and writer

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra