The new documentary Raw! Uncut! Video! takes as its subject the fetish porn video company Palm Drive Video, created by the legendary Jack Fritscher (founding San Francisco editor of the notorious Drummer magazine) and his longtime companion and husband, producer Mark Hemry.

Fritscher’s story alone could provide material for several documentaries: he attended a Catholic seminary for both high school and college (remarkably remaining celibate throughout), became a tenured professor and assumed a variety of academic posts at universities and art institutes, wrote novels (including 1968’s I Am Curious (Leather)) and non-fiction works (including the first book to investigate gay Wicca and witchcraft) and made videos and photographs that are now in important collections around the world.

Growing up in the repressed 1950s, Fritscher became a member of the army of lovers and perverts who moved to San Francisco in the early ’70s to explore their homosexuality. In 1977, he became editor-in-chief of Drummer, a magazine devoted to the “leathersex” lifestyle—a particularly extreme expression of the gay sexual militancy that became the driving force of the liberation movement in the West: men unrelentingly pursuing their sexual desires and fantasies as a core part of their lives.

The international distribution of Drummer spread articles about and images of leather and rubber styles and aesthetics and BDSM (bondage, discipline, dominance and submission, sadomasochism) practices around the globe, unapologetically promoting a gay movement without boundaries—a politically sexual radicalization of homosexual freedom. Fritscher also instigated the sexual appreciation of larger gay males—known these days as “bears”—and of older gay men, launching the “daddy” revolution that still holds sway in gay culture.

Credit: Courtesy Alex Clausen and Ryan A. White

When Fritscher met Hemry the night after the White Night riots (triggered by the light sentencing of the man who assassinated pioneering gay politician and activist Harvey Milk) in 1979, a long and happy union began. The couple formed just on the cusp of the advent of HIV/AIDS, a pitiless disease that would decimate the gay community and, for some, put the brakes on the extreme militancy of gay sexual liberation. The couple eventually left San Francisco, the epicentre of the so-called “gay plague,” for a bucolic ranch in Sonoma County, where they started their porn company Palm Drive Video.

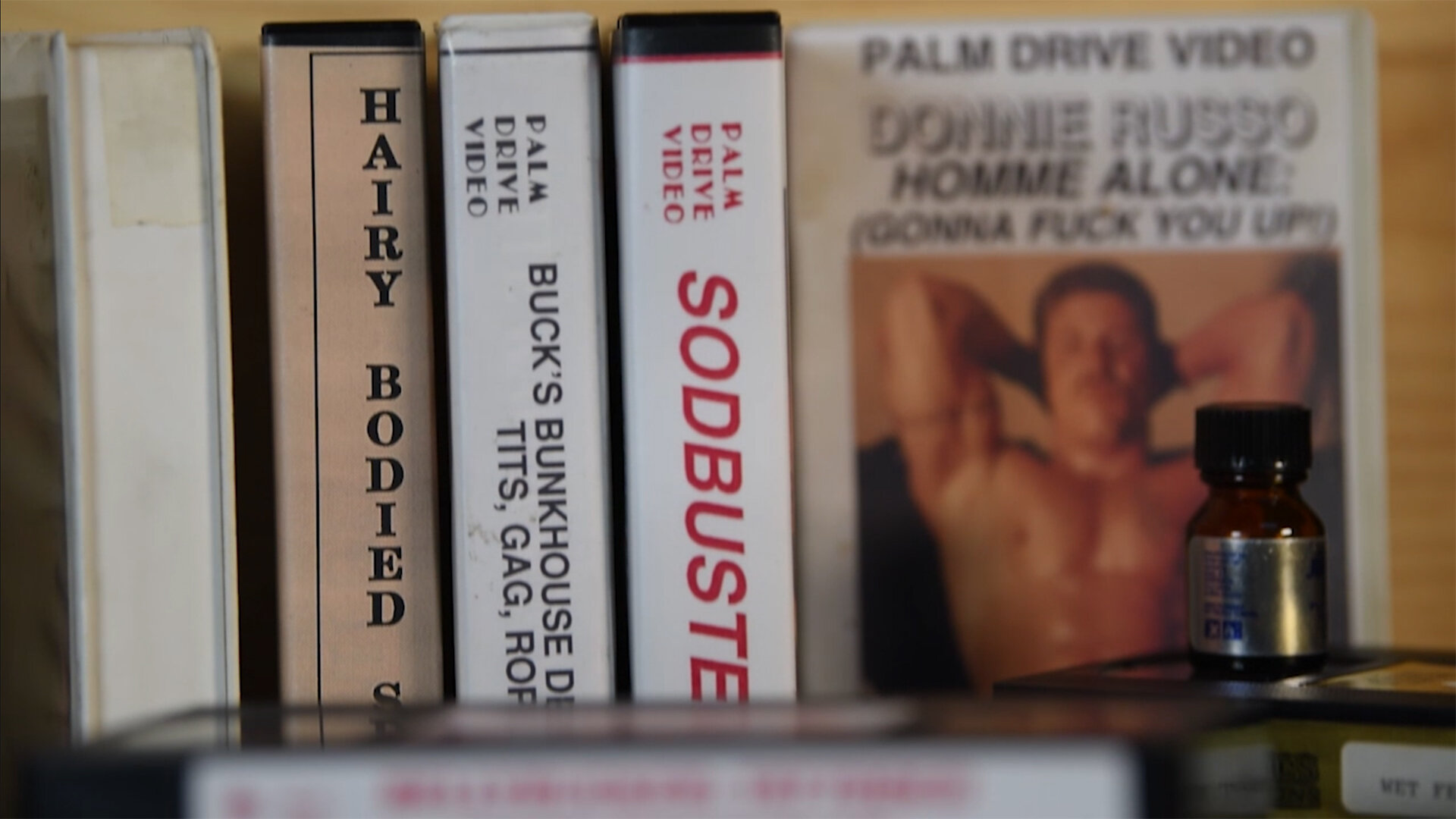

They specialized in solo sexual performances by authentically masculine men, cowboys or construction workers who they would meet in their everyday lives. In the more than 150 videos they released from the 1980s until 2001, guys pose naked or in fetish gear—from leather to football uniforms to caveman costumes—talk dirty, use unexpected items as part of their sex play (a plastic toilet plunger?), are tied up and dominated and, in the company’s most notorious videos, fuck mud and have their faces rubbed in vomit. As the couple produced these videos, their compound became a kind of safe-sex haven for those lusty fellows who sought an unfettered space for complete freedom of sexual expression, including scenarios of raunch, kink and confession.

The documentary by Ryan A. White and Alex Clausen, which screens until Aug. 22 at the Vancouver Queer Film Festival, admirably explores the life and fantasies of this kinky gay married couple—two men who managed to keep the tradition of militant gay sex going after the AIDS crisis of the ’80s and ’90s and into the repressive era of gay assimilation. I recently talked to the filmmakers about their experiences making the documentary.

On one hand, your documentary Raw! Uncut! Video! seems like a time capsule, but for the uninitiated or for people who didn’t live through that period, it almost seems like science fiction. The porn that Palm Drive Video was releasing was a kind of extremism that is almost shocking today, especially for younger audiences. Are you expecting blowback or do people take it as a strange document of a bygone era?

Alex Clausen: It’s hard to know. So far the reaction has been fairly positive. Older folks have had a take like, “I never really thought of looking at fetish porn in that way.”

On social media, I get comments for things I don’t consider offensive at all—a person putting their arm around someone else’s throat while they’re kissing them, for example. I’m not saying this is how everyone responds, but there’s this strong idea these days of harm or safety, coercion or permission. Do you find it strange, the way that the zeitgeist has shifted to such a degree that those images are more shocking now than for a previous generation of gay men for whom it was just normal behaviour?

Ryan A. White: One thing that’s interesting about the kind of conversations we’ve had with folks about the film is the idea of the porn archive. When we look at gay history, going back to the 1960s, the 1970s, there’s not a whole lot of visual archive of sexual cultures in particular. So we’re looking at the archive of pornography as kind of a site of history, where we can find our lineages and our histories, where we came from, how we got here. That angle has been quite productive when we’ve been talking to folks. People will say, “I get what you’re doing. This is way outside my box, but I get it.”

But at the time those videos were made, they were an expression of someone’s actual sexual life. It wasn’t intended to be something confined to an archive. Sometimes I feel the same way about my work—you don’t want to be forced to put it in a context that’s not right. In your film, [American writer and feminist] Susie Bright—I love her—said that the stuff from Palm Drive Video should be at the Whitney Museum of American Art, that it wouldn’t be out of place there. In one way, I know what she’s talking about, but on another level, I have mixed feelings about it because it’s not something necessarily to be curated, it’s the way that I chose to live my life and my sexuality. We’re in an era of judgment, where morality seeps into a lot of the political discussions going on now. Is that something you have to tippy-toe around or can it be just presented as part of people’s lived experiences?

White: Something in the film’s exploration of fetish, which Jack and Mark talked a lot about, was the trust between them and the folks who are in their films. And I’m hoping that aspect of the film, perhaps, pulls away some of the hard reaction to, “Oh, is there consent?” I would hope that maybe people are drawn in a little more because it’s clear that this was a safe space for people.

Credit: Jack Fitscher

When you talk to the mother of the straight guy who’s a bit ambivalent about what he did in the Palm Drive videos, it’s not like he has negative feelings towards that; it’s something he knows he doesn’t need to be ashamed of. But it’s reassuring that it’s his mother who tells him that. In the film, there is that element of trust and consent, and of forming relationships with people. But putting it in the context of the more contemporary leather scene, do you think the scene has become more like fashion? Have elements of the original scene gone underground, or are not as vocal as they once were, because they think there might be disapprobation or a kind of scrutiny on what is done in the scene?

White: We had a lot of conversations about this kind of stuff with Jack and Mark. Toward the end of the documentary, Jack’s going through some Super-8 footage that he shot in the ’60s and early ’70s, before they did Palm Drive Video. He made a comment that everything was so homemade back then. There were no stores that sold all this bondage gear. You made that yourself. You found some rope. Whatever you had in your garage or in your toolbox suddenly became part of that exploration.

I love that boot with the two little straps on it so that you can put it on your face. That would be high fashion now, but it was obviously improvised. I’m definitely stealing that idea.

White: That was neat, seeing the stuff that they had saved. Now there’s been this commercialization of sexuality and fetish. People have easy access to ball gags or harnesses or whatever. But going through the archive with Jack and Mark, and going through their garage, where they have a lot of costumes and things they’ve saved over the years, it brought us back to how these folks were pioneering this scene, looking at what they had available and asking, “How can we make this sexy? How can we integrate this into our erotic lives?”

I like the irony of the fact that the AIDS crisis almost forced people to become more extreme in their sexuality, or at least to explore more extreme fantasies. Because, in a sense, the SM scene, and what Jack and Mark were doing, was safe sex. They were shooting individuals, usually not more than one person, which was like built-in safe sex. But back in those days in the ’70s, early ’80s, post-liberation but pre-HIV/AIDS, a lot of gay men seemed to live their lives like what was going on in these videos. There was a much more militant sexual attitude, where maybe the average gay man, when he wasn’t working, would sometimes live his life like he was a porn star. In the film, Mark said he had a day job, but as soon as he came home, it was this whole other highly sexualized life. Is there that same kind of outlet now for people or do they not need it in the new era of assimilation?

White: For queer folks, with having more acceptance, in not feeling confined, perhaps that pressure is not there as much to enact more extreme fantasies. Maybe this is not exactly answering your question, Bruce, but I feel that in a lot of ways the AIDS epidemic did put a big damper on the idea of queer folks just doing whatever they wanted to do.

There are speed bumps sometimes, but AIDS was more than just a speed bump.

White: It was a pretty big speed bump. Jack and Mark retreated because of AIDS. They left San Francisco, they got this ranch in Sonoma County, California. But then at the same time, they maintained that sort of day-to-day sexuality through their filmmaking. Jack didn’t say this himself, but I see it in Jack’s filming—the camera was, in a way, his dick. While Mark would be off at work, Jack was able to have these guys come over to the house, and Jack would get to have these scenes with these guys, push them and get them to do what they wanted to do and explore. But it was safe because he was behind the camera and he wasn’t actually physically engaging with them. And then Mark comes home and goes through all that footage and then gets to have his own sexual experience as the editor, the person who brings it all together. The filmmaking aspect of it kept them going and kept them active sexually, but in this very safe way. Then they had this creative artistic output in the end.

Credit: Courtesy Alex Clausen and Ryan A. White

They embodied both sides of the gay experience, in terms of their being an extremely long-term couple who have this very loving relationship, which fits in more today with the model of marriage. But they had their cake and ate it, too. When you look at that gay militancy in the late ’70s and early ’80s, every city had a number of dedicated gay leather bars. The very act of liberation, after having repressed your sexuality for so long, was your sexuality bursting out of the closet, where suddenly anything was available to you. What do you guys think about the fact that that no longer exists? Or does it exist and I’m just not tuned into it?

Clausen: I hope those things are going on and I hope it’s without social media, without being covered by the media. For some of those things to be successful, it can’t be super accessible like everything is now. When everything is so well covered and documented, it loses its specialness.

That whole generation of gay pornographers, like Peter de Rome, Wakefield Poole, Jack Deveau and Fred Halsted, they were very educated, very cultured men. They know a lot about the history of eroticism and about de Sade and those kinds of things. Did you find out what Jack and Mark’s references are? Drummer was almost like a magazine for the refined leather men, even though it was super dirty, because there were also articles about other things.

White: One thing about Drummer was that it was before there were apps, before there was the internet. You met people in Drummer—the whole personals section was incredibly important. That’s how men who were into that kind of fetish sexuality met each other. Yes, there are hot photo spreads, and Jack always considered himself something of a—not an anthropologist, per se, but he would see what was going on in the scene in San Francisco or in New York, what was going on at the Mineshaft. Are cigars “in” this month? Then he would do a story on cigars or on cowboys or whatever. You might not have known you were a cigar fetishist until you saw some hot dude in Drummer smoking a cigar. Then you’d look in the personal ads and find all these cigar dudes.

Jack is almost like the late American fashion photographer Bill Cunningham of the leather scene. He not only observes the zeitgeist, but he ends up influencing it as well. What about this idea of the performance of masculinity, the performance of gender and whatnot. When you see, in the film, the way Jack found the models—I hate to use the word “authentic,” but they were these super masculine guys, some of them working class. It used to be a fetish for some people if they were in a bar and met a real ditch digger or rancher or farmer. Does that same kind of authenticity exist in our contemporary culture?

Clausen: Near the end of the film, when they talk about the end of Palm Drive Video, they talk about the difficulty finding the models that they were looking for, what they considered their authentic models.

Credit: Courtesy Alex Clausen and Ryan A. White

Maybe gay bars in the past were more of a melting pot and I’m not sure people have the same access anymore.

White: The culture has changed so much, too. Jack and Mark would go to gay bars searching for models, but they would also go to the county fair, be hanging out around the bathrooms. They’d go to construction sites. Pick up hitchhikers. Some of the models were dudes they picked up on the side of the road.

It could have been dangerous, I’m sure.

White: For better or for worse, and I think for worse, that kind of cruising culture is pretty much gone. Most folks don’t go to public restrooms to look for sex anymore. Some might, but fewer than in 1987 or 1977.

There’s a lot more cameras, there’s more monitoring of it. It’s more clamped down on. Did you talk to Jack and Mark about how they view more contemporary ideas in the gay world about sex and sexuality?

White: They absolutely love everybody showing off online. They love that.

They probably love OnlyFans because they kind of invented OnlyFans in a weird way. It sounds funny, I know, but had there been social media back then, they would have been on top of it. But it was melancholy for me when, near the end of the film, they were wondering where all this stuff would end up. Would it be in a gay archive or maybe in an art context, or would it be the dumpster? Do they have a plan for archiving all their stuff?

White: They have identified a few major archives within the United States that deal with sexuality and sexual culture who are going to be taking some of the Palm Drive archive. They were such a boutique studio, selling everything on VHS out of their own house. There were other companies doing similar things, but then, who’s got the market cornered for mud fucking?

The mud fucking is the image that nails the whole brand the best. I love that. I’m going to steal that, too.

Raw! Uncut! Video! screens at the Vancouver Queer Film Festival until Aug. 22. Bruce LaBruce’s 13th feature, Saint-Narcisse, is currently on the festival circuit. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra