Edward Roy doesn’t mind being called a perfectionist. “Sometimes people I work with say I’m too hard on them,” he says. “But it’s not for the sake of being hard; it’s for the sake of making the work better.”

That said he’s also more than willing to take criticism. “I don’t want anyone kissing my ass or telling me something’s great when it’s not. You don’t learn from that.”

Roy’s in the midst of perfecting his new play The Golden Thug; the Topological Theatre production receives its world premiere at Buddies In Bad Times Theatre on Thu, Apr 6.

It’s a fictional account of the last days of legendary writer, notorious criminal and queer icon Jean Genet. In April 1986 Genet checked into Jack’s Hotel in Paris, dying of cancer and set on finishing his last novel, the posthumously released Prisoner Of Love. What happened during his stay there is somewhat of a mystery.

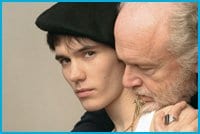

The Golden Thug imagines Genet (played by stage-great William Webster) checking in and meeting a bellhop named Pierre, a sexually confused teenaged delinquent (played by fresh-faced recent National Theatre School graduate Andrew Hachey). The piece moves back and forth in time, between Genet’s last days in the hotel with Pierre, and scenes from his youth in prisons, brothels and other seedy places. Hachey also plays the young Genet in flashback scenes.

Back in 1998, Roy, a longtime Genet fan, decided he wanted to write a play about the late author, so he booked a plane ticket to Paris. He visited the many bars, clubs and cafés Genet frequented, caught his play Deathwatch, which was running at the time, and explored the seedy underworld of Paris nightlife.

After returning to Canada, Roy sat down to write and in 2000 the first workshop was presented at the Theatre Centre. He describes that version of the piece as “an imagistic retelling of Genet’s life from birth to death.” At the end of the process he was left with a 158-page script and a sense of dissatisfaction. “I realized then that I didn’t want to make a bio play,” Roy says. “I wanted something that would evoke the essence of Genet, but it had to be very much in the present.” Roy then did what every smart writer does when working with historical characters. “I knew the history,” he says. “But then I said ‘Wouldn’t it be more interesting if this happened?'”

Genet was known as much for his notorious life as for his body of work. Born the son of a Parisian prostitute, he was orphaned early in life and made a ward of the state. He was first sentenced to prison for theft at around age 15. “It was a horrible time for him because he was poor and isolated,” Roy says. “But it was also a glorious and beautiful time for him because he was a sought-after young man and he was gay.” Genet became popular early in his prison career for his willingness to trade sexual favours for social status.

“What those kids went through was unspeakable,” adds Webster. “They were forced to work constantly throughout the day, with breaks only for prayer. They were deliberately undereducated, just enough to keep them down.” Genet however, took an interest in literature early on, and even started to write while in prison, although guards often confiscated his work.

The following years saw a career in the military, additional prison time, political activism and a rather substantial body of work, including novels, films, poetry, essays and stage plays. “I admire Genet partially because he was one of the century’s first interdisciplinary artists,” Roy says. “He used a variety of media to forward his own political and artistic agenda.”

Roy borrowed the title of the play from an early biography of Genet. “It’s a great metaphor for his life,” he says. “He took the shit he had to swallow and turned it into gold.”

“There’s also an alchemical reference,” says Webster. “The notion of someone who is actually able to take the dross of their lives and turn it into something unique and beautiful; that really captures the spirit of Genet.”

This is not the first time the Buddies space has seen a play exploring Genet and his work. In 1978 a landmark production called Flowers, A Pantomime For Jean Genet, was presented by choreo-grapher Lindsay Kemp at 12 Alexander St, then known as Toronto Workshop Productions. The piece was an almost entirely physical exploration of Genet’s novel Our Lady Of The Flowers. Webster was lucky enough to have seen it.

“I think I saw it at least five times,” he laughs. “It was such an exotic piece. They were mostly naked, had blood dripping from their mouths. It was amazing coming out of that performance how shocking the world was. Time had been almost made to stand still.”

This is also not the first Genet-related piece for Roy. While in the early stages of development on The Golden Thug he directed a production of Genet’s play The Balcony with the graduating class at Humber College. “I love Genet’s plays,” he says enthusiastically. “They require a heightened theatricality and that’s a thing I champion. I want theatre to be an alternative to film and television. We should be trying to broaden our vision, not just offering entertainment all the time.”

Another artist who shared this vision was the late great Toronto theatre pioneer Paul Bettis, who took on the role of Genet in earlier workshops. In an awful, poetic twist of irony, Bettis passed away last fall of cancer, as Genet did 19 years earlier. Roy has chosen to dedicate the piece to Bettis for both his memory and how instrumental he was in its development.

Roy recounts an evening during the workshop: While he was receiving congratulations from the other members of the company for certain developments of the piece, Bettis, is his classic style, announced, “But darling, there’s no plot!” Rather than being upset, Roy was inspired. “It was one of the greatest gifts he ever gave me,” he says. “Everyone was upset, but I remember walking home from rehearsal and thinking, ‘He’s right.’ That was the power of working with Paul. He was irascible and critical and marvellous. I still miss him.”

Roy’s connection to Genet goes much further than simply being a fan of his writing. “A lot of things about Genet’s life parallel mine,” he says. “I was orphaned as a child, twice. I grew up poor. I was a delinquent. I had run-ins with the law. I knew what it was like to be a thief and I knew what it was like to be incarcerated.

“People sometimes can’t believe where I come from,” he says. “I was raised by an illiterate mother. But one day I found a book and started reading. That reading fed me for a lifetime.”

Despite his painful past, Roy has been able to let much of it go, partially through his discovery and practice of Buddhism. “I’ve been studying Buddhism for 25 years,” he says. “It’s helped me to look at the painful parts of my life and transcend them.”

While the play is full of references to memory, Roy is quick to point out that Genet himself was neither nostalgic nor sentimental in his work. “He knew memories are not authentic because we reinvent them,” he says. “I’m not nostalgic.

“I’ve had a very interesting past, but I’m more interested in what’s happening now.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra