First novels are criticized with such merciless scrutiny, it is a wonder that their debut status is the very attribute for which they are publicized.

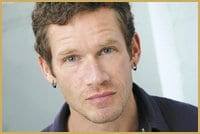

Brett Josef Grubisic’s freshman effort, The Age Of Cities, however, is met with little skepticism: the many years under Grubisic’s belt in the field of English literature immunize him from being labelled a novice writer.

Grubisic earned his MA in English literature from the University of Victoria sometime in the 1990s — he can’t remember exactly when — where, a theatre critic, he wrote for the student newspaper. He received his doctorate in 2001, simultaneously studying and teaching at UBC, where he is currently a professor. Although he has edited two compilations of short stories, and been a regular contributor to Xtra West, he had never attempted his own novel.

The Age Of Cities takes place in 1959 British Columbia: the Cold War is raging insidiously across the continents and social upheaval is imminent throughout the world — but Winston Wilson, the novel’s protagonist, wouldn’t be the person to tell you so with any sort of urgency.

Very little, in fact, can shake Wilson’s composure — aside, that is, from his unusually and inexplicably swollen foot. After a fruitless visit to a downtown podiatrist, he runs into Dickie, a flamboyant and fiendishly witty city boy. The encounter leaves him wary of, though charmed by, his new acquaintance.

As Dickie introduces his newfound pet to his dilettantish posse, the reader is deliciously confounded as to how Wilson, a resourceful librarian, can be as unsettlingly ignorant of the posse’s obvious homosexuality as he is.

Wilson is taut, rigid; an air of restraint blankets him throughout his story, even as the context of the novel, the conservative 1950s, sustains his naïveté.

Having extensively read mid-century Canadian literature, Grubisic met no challenge writing in the dialect of the period with such fluidity. But even the hilariously wicked dialogue is outdone by the lush, vivid, and delicately crafted settings described throughout the book.

The meticulous attention to detail with which Grubisic constructs the bars, the restaurants, and even Stanley Park provokes the desire to live in this otherworldly Vancouver, based as much on the images in the author’s mind as on the authentic city.

Ironically, Grubisic’s detachment from the period was what inspired the novel’s lovingly formulated setting. “Reality is always less interesting,” he says. “As an era that had finished before I was born, I didn’t feel a huge personal investment in representing it with pinpoint accuracy.”

Accurate or not, it was 1950s Vancouver bar space, which he was researching for a separate project, that piqued his interest in the era. “That secretive and coded and half-visible world of our queer ancestors was both fascinating and foreign. As something quite alien to me, its values and form really held my curiosity.”

Grubisic detects a strong sociopolitical connection between that bygone age and today.

“I think that right now in Vancouver, and absolutely right now in many places across the globe, there are women and men who are forced to rely on secretive and marginal places and relationships because they understand the unwelcome consequences of visibility. Even I know that. I can be as queer as I like in certain places. In other places, outside of cosmopolitan urban spaces, I know that made visible, my queerness can get me into trouble or upset the locals. At such times I can, like the men in The Age Of Cities, choose to blend in or can seek out dark corners in bars and parks to find my own kind.”

Perhaps the most interesting and original aspect of The Age Of Cities is its unusual conception as story within story: found inside a hilariously misogynous home economics textbook, Wilson’s manuscripts are discovered by an anonymous, invented editor, whose introduction concludes the novel.

Moreover, Wilson ends his story, written in the third person, with two epilogues — one arguably more pessimistic than the next. “Your certainty as a reader is up in the air,” Grubisic explains, adding that the atypical structure adds dimension to the book.

The novel was published by Arsenal Pulp Press, whose policy is against publishing ordinary fiction. The fact that it was the only publisher Grubisic approached makes it obvious he’s not exactly bracing himself for major commercial success.

“I don’t write with gaining a huge audience as my goal. Were that the case, I’d write the most formulaic of bestseller pap, a bit of Dan Brown mixed with Stephen King and Tom Clancy. Voilà: instant airport bookstore visibility from Athens to Akron.”

He continues, “Writing about, say, a heterosexual man’s quest for self-fulfillment because it would attract more readers would make me feel cynical and a sellout. Maybe in a sense even a traitor. And if I’m going to sell out, I may as well do it big time and write formula pulp fiction.”

I wonder if he considers writing to satiate the interests of his own sexual demographic selling out. “I’m not inclined to see sexuality as somehow separate from identity,” he responds. “So I wouldn’t say I was writing about sexuality any more than Margaret Atwood or Douglas Coupland is writing about sexuality. My focus is on intersecting groups and communities, and my interest is in the fluidity of each and what the implications are for people who find new affinities or reject old ones.

“What happens to the self when it has to discard parts of itself in order to make space for newly forged bits? These concerns are not particularly about sexuality, even though the specific social context in The Age Of Cities is queer, queer, queer.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra