When many of us were growing up, the rules were laid out in pretty much every children’s book: girls liked pink bunnies, Barbie dolls and playing mommy; boys preferred toy guns, sombre colours and sending GI Joe on covert killing sprees; and woe betide any child who deviated from these social “norms.”

But what about the kids who defied conventional roles? Where were the books for Jenny, who dreamed of ruling the seven seas as a ruthless pirate king? Or for Todd, whose pirouettes were so graceful and filled with flourish? For the kids who fall between those established gender lines, there is little media that reflects their rich and varied lives.

Flamingo Rampant stands as a proud exception to the rules of children’s publishing. Established by activist and author S Bear Bergman, this crowd-funded micro press produces books with themes that support LGBT families and gender-independent kids.

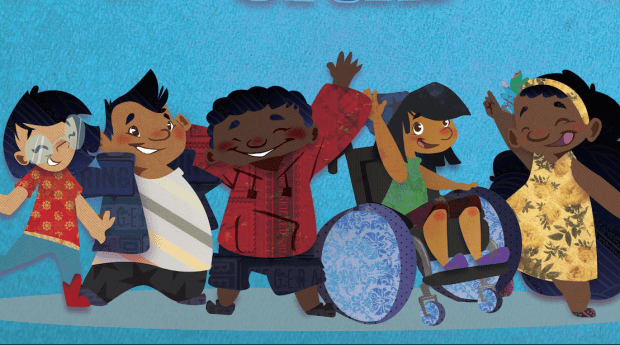

“We have a few core commitments,” Bergman says. “Half or more of our books feature kids or families of colour, half or more feature girls and women and all of them had to be LGBTQ positive. I don’t mean just mentioned — I mean joyously celebrated.”

As a well-regard activist and published author, Bergman invests a lot of time examining and commenting on the tangled issues of gender and sexuality. But it’s the role of father and co-parent that inspired his entry into children’s publishing.

“My husband J Wallace works for the Toronto District School Board. He does a lot of education teaching teachers how to create gender inclusive classrooms and conversations about different family units.”

As part of this work, Wallace orders a number of the children’s books available to teachers as resources in encouraging this atmosphere in their class. He and Bergman found the existing materials discouraging — as did their four-year-old son Stanley.

“This box of books arrived, so we cuddled up to read some at bedtime. The first was a difficult story about a kid who was different and got bullied. The second was more or less the same.

“Stanley started to look uncomfortable. All of these books have so much bullying and harassment and violence. He looked up at me and said ‘I don’t want any more bully stories.’ My heart just broke. I put him to bed, got out a legal pad and started crunching numbers for another Kickstarter campaign.”

Bergman had utilized the online fundraising service once before to raise capital for his first two children’s books, Backwards Day and The Adventures of Tulip, Birthday Wish Fairy. The success of these two showed the author that there was an audience for gender inclusive children’s books, but a paucity of material.

The second Kickstarter campaign proved a huge success, raising enough money to publish the series of books Bergman had envisioned when creating Flamingo Rampant.

“I really wanted to do six books and sell them as a curated set,” he says. “I think, as a set, they do something that has never been accomplished before. They create a picture of lesbian, gay, bi, queer family life that is robust and various and inviting and joyful and welcoming.”

It proved an ambitious undertaking, particularly in finding illustrators for the works Bergman commissioned from friends and colleagues within the writing community.

“I asked everyone I knew who was a good writer and a good storyteller if they had ever considered writing a children’s book. For some I took the idea to a writer and asked them if it sparked something for them to write.

“Finding illustrators was more difficult. We had a very intense commitment to racial diversity. One of the real pitfalls of having a racially diverse children’s book is that some illustrators just draw everybody the same and then colour them differently.”

Bergman wrote the first book himself, a timely tome called Is That for a Boy or a Girl? For any parent of gender non-conforming kids, it’s a question that can give rise to a great deal of frustration.

“It just comes up constantly,” Bergman points out. “And sometimes it’s over the most ridiculous thing. Like, Stanley had lice and I had to get lice shampoo. The pharmacist asked me if it was for a boy or a girl. His reasoning was that girls have longer hair and need a bigger bottle.

“Or I go to the library and look for videos about sea creatures. They ask if it’s for a boy or a girl. What the fuck do you care? It’s sea creatures!”

The goal of Flamingo Rampant books isn’t to discount that boys and girls may like traditionally gendered things, but rather to open up the field of play. So Jenny can be a pirate king who plays with dolls, and Todd can pirouette gracefully in army fatigues if he wants to.

“So many children are a hearty blend of things they like,” Bergman says. “If nobody tells them that there’s a whole set of things they’re not supposed to like, they feel quite free to like whatever they want.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra