To close the year-long celebration of Art Metropole’s 30th anniversary, Andrew Zealley has organized Halos, a massive retrospective of Robert Flack and David Buchan’s art works and personal paraphernalia. With the recent changes and upheavals at Art Metropole, the works of these artists who died early remind us that art communities have the potential to be astonishingly loving and supportive as well as vulnerable to abrupt endings.

Halos marks not only the gallery’s longevity, it marks an era, a time when No Wave was kicking up the streets in the Lower East Side, and when artists and musicians worked closely together. While NYC was exploding with the likes of Lydia Lunch, the Lounge Lizards and the Bush Tetras, Toronto’s art scene was bursting with talented and critical minds such as General Idea, the Homo Genius Collective, Tim Guest, David Rasmus, Andy Fabo, Stephen Andrews, Regan Morris and, of course, Robert Flack and David Buchan – to name only a few.

As post-punk blurred into No Wave, artists continued to play with plasticity in culture, often specifically targeting the Holy Trinity of ultraconservative politicians at the time (Margaret Thatcher, Brian Mulroney and Ronald Reagan). The epidemic of violence, poverty and unemployment of the 1980s turned into an even uglier monster when we began to lose our brothers, friends, lovers and sons to HIV/AIDS. Among the many bright lights dimmed by the epidemic were Flack (1957 to ’93)and Buchan (’50 to ’94). Both men remained dedicated to their artistic processes up until their deaths.

Seeing Flack and Buchan’s work side by side creates an interesting tension. While both bodies of work are embedded in an important era of art production and gay identity, they opposes each other in style and content. Flack explored the body as a spiritualized vehicle where colour and form create soothing images that glitter with kitschy delight, while Buchan’s work relied heavily on art history, visual culture and commodity. Flack is light to Buchan’s dark.

Flack’s aesthetic is reminiscent of Jack Smith, where pastel colours and pretty objects such as flowers and chakra symbols were used unabashedly. Flack used multiple layers of acetate similar to animation cell painting. He would paint the reverse side of a transparency, layer them, then place the short stack onto a brightly painted background. In the Love Mind series Flack uses his signature layering technique with patterned images that are projected directly onto a body, then photographed.

Love Mind shows lush colours and form to explore male desire and sexuality. In one image from the series an ass is splayed – exposing a rectum and testicles, the light brown fuzz on the butt and thighs – giving additional texture to the red, orange and yellow cobweb shaped projection, imparting a mystical quality to the male body.

Where Flack embraced a kind of divinity, Buchan worked within a more academic framework that critiqued culture and the idea of the product. His large-scale photo-graphs employ a language similar to Cindy Sherman’s Untitled images from the mid-1990s where Sherman donned elaborate costumes of the 18th century that parodied an idiom between past and present. The work of Buchan successfully appropriates classic paintings with meticulous lighting and magnetic imagery. Where Sherman’s Untitled self-portraits play with sexualizing baroque imagery, Buchan’s pieces takes classical imagery a step further.

Mimicking After The Bath by London, Ontario painter Paul Peel, in Twinatron, Buchan photographs Art Metropole director Ann Dean’s twins. The children, as in the Peel piece, are naked and gazing into a warm glow. Where the Peel piece has the children warming to a hardy fire, Buchan situates the young subjects in front of a Sony television as the TV screen reflects their blank stares. This piece admits to the reality of the modern baby-sitter and explores our persistently passive gaze that forms TV’s inherent narcissism.

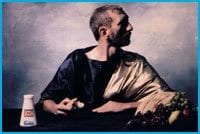

We have become so accustomed to advertisement that often it feels as though critical attention has become moot. Where shopping is a hobby, wearing labels increases social status and intelligent critique is considered unpopular, Buchan’s pieces profoundly resonate. In his largest piece, Eno, Buchan sits front and centre exposing a Romanesque profile while a sword floats with tip hovering above the crown of his head. Awaiting its swift descent, Buchan is pensive without projecting anxiety or panic. Flanking Buchan are clusters of grapes, apples, crusty Mediterranean bread and a large bottle of Eno. Anticipating its medicinal intervention, the white Eno bottle is in stark contrast to the chilly hues of grey and cobalt blue that dominate much of the photograph. What are we waiting for in this piece? Why does Buchan make us wait? The relationship between “making us wait” and Buchan’s own anticipation with his health is a juggling act that he manipulates flawlessly in this image.

The pieces that give this show its title, Halos, dangle the idea of mortality in front of us as both artists explore beauty, metaphor and death. Buchan’s Halo (sadly, it remains in its home at the National Gallery but there is a small reproduction on view) is an adaptation of Jacques-Louis David’s famous painting The Death Of Marat. Buchan lays slumped and inert in the tub. Death has entered the room, a spot of blood marks his pristine white turban, which emits light like a halo, yet the real halo reference is a bottle of Halo shampoo on the right of the picture. In David’s painting, Marat’s dead hand holds documents pertaining to the French Revolution but Buchan’s flaccid hand holds his Visa bill. Again, Buchan unrelentingly exposes the commonness of high art and the pervasive commodification of our everyday lives.

Flack’s Halo piece is a clean- edged composite of multiple layers depicting a clear blue sky, wide open and lacking any threat of storm or tumult. Floating on the top of the page is a circle of interwoven roses in shades of pink, ruby reds, yellow and mauve. The image suggests bliss or an ethereal quality, yet a darker idea bubbles to the surface – roses have thorns, their beauty is protected and they are capable of harm.

Flack’s Halo doesn’t have anything overtly brutish or dark in it, yet, because of how he died, I cannot stop asking how this image mirrors an understanding of his own death. Accompanying the exhibit is a soundscape created by Zealley entitled Empathetic Ear that combines Flack’s record collection and a psychic reading. Words and songs weave into each other, ominously, playfully. Listening to it, my stomach ached a little. I felt as if waiting for someone who would never show up.

Buchan and Flack explore mortality as something profound but, ultimately, both viewed death’s presence very differently. This show is a valuable memorial to two fine artists who were in the throws of international attention just before their deaths. Halos has the potential to remind us of both the strength and tenuousness of our lives and communities.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra