Despite being a country where the vast majority of sexual minorities remain closeted in their day-to-day lives and frank public discussions of gender issues are often discouraged, the Japanese LGBTQ+ scene has somehow thrived in a nebulous middle ground, and with ever-increasing visibility and diversity to boot. Queer entertainment has spread from Tokyo’s gay mecca of Ni-chome in downtown Shinjuku to many other parts of town, as well as cities all over Japan. Now on the rebound after the restrictions of the past few years limiting live event attendance, operating hours and the sale of alcohol have thankfully come to an end, both Japanese and foreign-born drag performers, DJs and event organizers are welcoming packed houses once more.

Xtra talked with Tokyo-based performers to get a window on this unique scene, from award-winning makeup artist and performer Pepe Paladini to legendary house mother Koppi Mizrahi.

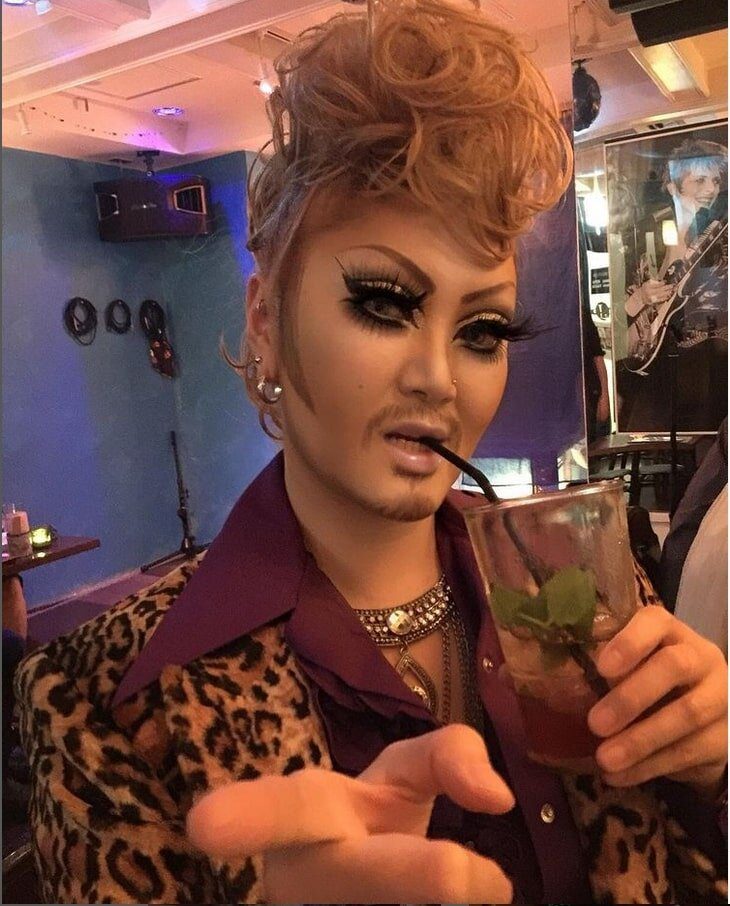

Sisen Murasaki, goth terror doll

At night, amidst the endlessly sprawling alleys full of bars and love hotels in the Kabukicho area of Shinjuku, you will find gothic DJ and drag queen Sisen Murasaki. Sisen is far from home, originally hailing from the mountainous Nagano region, famous for Olympic skiing and beautiful natural scenery. “Of course, a big part of our appeal is a city like Tokyo, but there is also another side of Japan,” says Sisen, who, despite being closeted growing up, still has love for their rural hometown. “When I’m there, I like to get lost in nature … I would go searching for the biggest tree I could find. You get the sense that there’s some kind of spirit, or God inside it. Even now, I like to keep plants around the house.”

In rural Japan, it often seems like time has stopped, and the same applies to people’s values and beliefs. “Japanese are used to seeing gay men on TV,” says Sisen, citing actor and cabaret singer Akihiro Miwa, who worked on such films as Black Lizard and Black Rose Mansion with acclaimed director Kinji Fukasaku, as well as Peter, the mononymous star of the cult queer film Funeral Parade of Roses. “The average person has a sense that queer people like us exist, but we are sometimes looked down upon.” Sisen, who from a young age enjoyed dressing up like a princess and playing with dolls, had to bear their share of childhood bullying. “My friends, they didn’t know any better, you know? Kids these days might have more of a sense that some people are born differently.”

Sisen eventually left rural locales for the bright lights of Tokyo, and in the early 2000s started performing in drag with a few friends. “I wanted to be a spooky, gothic-inspired drag queen, maybe like something you’d see in Dragula today.” Sisen was most heavily influenced by the stoic, doll-faced Mana, guitarist of glam rock band Malice Mizer and the founder of the gothic Lolita subculture. But Sisen also looked up to Japanese drag contemporaries of the ’90s and 2000s—famous campy queens like Onan Spelmermaid and Nadja Grandiva, the latter appearing in numerous pop music videos and panel shows, as well as arty queen and social critic/philosopher Vivienne Sato, who has helped create greater awareness of gender-bending art and drag in Japan by holding drag workshops in small towns and cities all over the country. “In the ’90s, many other queens were still inspired by Divine or Priscilla, and by 2000 it was Hedwig; we would go to see them every month at places like Department H.”

When it comes to famous gay spaces, none is more infamous than Department H, Japan’s oldest fetish party featuring rubber, tentacles, aliens, contortionists, BDSM, strip shows, suspension, wrestling, burlesque and, of course, drag. For 30 years it has been an institution along with its host, drag queen Margarette. This has led to even further mixing between gay, goth and fetish crowds as of late.

Most recently, Sisen has found their home behind the bar and in the DJ booth at DecabarS, a notable goth and fetish club that was recently featured on Netflix’s Midnight Asia series. Sisen first began to work as a DJ in the early years of social media, and as DJ gigs grew, drag tapered off. Sisen’s eye-catching androgynous looks and a sizable presence among the who’s who of the Japanese goth scene gained them a huge following on Myspace, which led to gigs all over the world during the 2000s, including a seven-year stint in Berlin. They are also a mainstay at events such as Casket of Horrors, a horror drag show consisting of both foreign and Japanese performers.

Angelix, musical king of disruption

While it is mostly drag queens who have dominated the Ni-chome nightlife and have fashioned their own place in the Japanese public imagination at large, there is also a small but significant community of kings here. Many drag kings in Japan, however, are in something of a bind: lesbians, by and large, are invisible in the Japanese public consciousness, and aren’t looked upon especially fondly. For a drag king who isn’t strictly lesbian, they might encounter problems of their own for not meeting even these expectations. Japanese gender-fluid king Angelix, meanwhile, simply does not give a fuck about any of this.

“I don’t really care about the ‘gay scene,’” she says. “I have both gay and straight friends; I’m not particular about labels or who I associate with. I think people should just do what they want.” Japanese queer culture has a dizzying number of categories and subcategories; Angelix resents this labyrinthine way of categorizing people. For as big a success as Rainbow Pride has been in Tokyo, for example, some queer folk have become rather irritated by it, or have become completely numb to it. “In Japan, we already had this sort of freedom before … I don’t really think [Pride] is important. People who like drag, for example, can get together and meet up anywhere. I sometimes question what it is [Pride organizers] are trying to accomplish nowadays,” says Angelix.

In Japan, there are specific boxes for not only who you identify and associate with, but if you are a performer, and the sort of work you do. In the past, a comedy queen would stick with being a comedy queen; they would be booked for a comedy event with an audience that was there specifically for them. But Angelix is a jack of all trades: a trained tenor who originally performed as a masked bioqueen, her repertoire encompasses everything from goth to jazz to traditional Japanese enka, sometimes with a bit of comedy thrown in, both as a solo act as well as with her band Death Trance Delilah.

In the past she’s worked in Ni-chome, her native stomping grounds of Yokohama’s Sakuragi-cho district, as well as shows for primarily straight audiences, even corporate gigs. “At first, I didn’t really have self-confidence. So I put on makeup and a dress; without being masked in some sort of way, I wouldn’t be able to do it.” Her original act was inspired by Dr. Frank-N-Furter from Rocky Horror, and many of her early gigs were at Sisen’s parties—the two remain friends to this day. Eventually, Angelix found that being a drag king was more her speed. However, this was a rarity in Japan where the king scene is quite small.

In many ways, the impetus for Angelix’s king persona began in her childhood. Though now identifying as non-binary, Angelix felt at odds with her assigned sex since childhood. “More than a woman, I used to feel like I should’ve been born a man. My parents wanted a boy, so they sorta raised me like one. I didn’t mind it … being tall and boyish. Of course I cared what my parents thought of me, but it didn’t bug me being treated this way.” Once her career got off the ground, Angelix broke the news of her identity in her typical direct fashion. “I really never came out to my parents, per se; instead, I just invited them to my show,” Angelix says. “I think they got the idea after that.”

Mx Terious, genderbending king of kings

Angelix has in the past performed with other Ni-chome kings, such as Mx Terious, the current organizer of the Kings of Tokyo drag show. They first began their drag career in 2013 while helping backstage at drag show Tokyo Closet Ball, and became a performer the next year. There is a common story of expats finding their true identity here, but Mx Terious was out from the time they were a high school student in Kentucky. “Japan is not so different from where I grew up,” they said. “There wasn’t even a vocabulary to talk about this; I didn’t learn about my sexuality until I read about it in a pamphlet in a therapist’s office.” In the time since, they founded their university’s gay-straight alliance, and travelled around the country attending queer rights protests. “I was out, but still I was careful; I wasn’t telling everybody under the sun I was bisexual.”

In Japan, Mx Terious began drag life as a bioqueen before embracing both androgynous and masc aesthetics. Their queen shows tend to be more dance-focused, while their king performances go back and forth from horror to comedy. The Kings of Tokyo show itself is a gathering of mostly expat drag kings spanning everything from choreographed group shows and lip-syncing, to puppetry and dating games. This is a stark difference from many king shows, or even more mainstream theatre acts like Takarazuka, where a “king” sort of role is expected to have a strong image as opposed to a parodic one. Foreign kings like Mx Terious hope to challenge this convention. “You can embody a masc presence on stage or … you can tear it down,” they say. “People always talk about hypermasculinity and how funny it is, but when it comes to the actual stage production (in Japan), it tends not to be.”

Unfortunately, a constant issue with king shows in Japan is the difficulty of holding on to performers. “In general people seem to try it, and then go on and do something else,” says Mx Terious. Specifically, for kings in Japan, embracing the masc side of themselves often means transitioning. “Dating here is really cisgendered,” Mx Terious says. “There’s always expected to be a man and woman in a relationship.” Trans men are expected to be super masc, trans women super femme and bisexuals are pressured to fall on one side or the other. There is seemingly no other way to date here. This is often formalized in the Ni-chome dating scene, where some bars will give you a drink coaster according to the specific type of partner you are looking for. “My trans friends feel pressured to be super masc, when that’s not really fair to them. In my experience too, I’m always asked ‘Which “one” are you attracted to?’ But that’s not how I categorize things; that’s not how my brain works. What about personality?”

Pepe Paladini, beautiful horror for hire

Whether you’re hoping to look your most glamorous or your most disgusting on stage, the person you ought to see is Pepe Paladini. Originally from Brazil, this award-winning artist’s work can be seen with increasing regularity on the stages and screens of Japan, both big and small. Their oeuvre includes painting the ghoulish visages of Sadako, Kayako and Toshio (the world-famous ghosts from horror classics The Ring and The Grudge) for the remake-cum-crossover Sadako vs. Kayako, as well as doing makeup and prosthetic work for anything from lingerie shoots and samurai movies to lots and lots of their drag siblings.

Sometimes, it is Pepe who becomes the canvas. Under the moniker Penelope Moon, they showcase their mastery of special effects makeup and prosthetics, perhaps donning a fabulous new beak, or sporting some extra ears, a pair of horns and plenty of blood and guts, walking the line between beautiful human and monstrous creature, inspired by their love of the works of Guillermo del Toro, among others. On other occasions their gender-bending performances feature Penelope as a curious amalgamation of male and female—more of a god or monster than human. It was in drag that Pepe saw Ni-chome for the first time. “I was just happy to be around people I recognized as a community … I liked myself more and more as a woman.”

In fact, Pepe started their drag career and their life in Tokyo performing at a show bar whose Japanese performers were predominantly trans women. “It began as work, then I saw the girls and thought, ‘Maybe I’m like them, too.’” However, they also noticed the difference between their own performances and the sensibilities of their co-workers. “For me, drag was more about art, and for them it was more about being beautiful.”

While Pepe’s drag would sometimes feature a playful mix of male and female, for their contemporaries, womanhood was no laughing matter. They had clear notions of what was and wasn’t acceptable, including interest in anyone but cis men. “Their thinking was, ‘Why would someone become a woman if they wanted to date a woman?’” Pepe, who is now undergoing their own transition, has also experienced discrimination within the community. “Even the gays don’t know the difference,” says Pepe. “At some places I get charged as a guy; it bothers me a lot because they seem to think I’m just coming here for a discount.”

Credit: Alejandro Sierra

Pepe first came to Japan at only 17 years of age, and struggled to find their identity while working in a rural factory town and teaching themselves Japanese. They have had a long love of makeup, stemming from attending theatre camps and acting classes in their childhood. When finally given the chance, they chose to move to Tokyo to try to make it in the film industry. However, they also maintain a strong connection to their home country, and in 2020 were given the Focus Brasil Award in visual arts, an award for Brazilian expats who have made positive contributions to their community abroad. There are now over a quarter million Brazilians in Japan, and many, like Pepe, have Japanese ancestry. Pepe’s relationship with their home country is somewhat strained by the current social and political climate. “In Brazil, we are the country that kills the most trans people, but we also have a lot of awareness (in Brazil), and are fighting back and protesting against this.” By contrast, though Japan is not a religious country, trans people have achieved comparatively little recognition or visibility. “Here in Japan it’s safe … I can go out without fear of being beaten, but you still see a lot of prejudice.” However there have been some strides: women’s universities accepting trans women, and a landmark same-sex partnership law in Tokyo passing last fall, offer a degree of hope.

Koppi Mizrahi, Asia’s ballroom mother

Credit: Courtesy of Koppi Mizrahi

There is another side of Japanese drag that in the past had only a tenuous connection to its LGBTQ+ roots, though a reunion looks to be on the horizon. Madonna’s hit single “Vogue” first brought mainstream attention to ballroom culture, and Japan was no exception to this. Here, it was thought of more in terms of a dance craze, so the impact was short-lived. However, the past few years have seen a change due to the rise of Japanese ballroom queens and their houses, including the now-legendary house mother Koppi Mizrahi.

Koppi first found voguing as a college student in Tokyo in 2006 when her university’s dance team took part in a voguing event. Intrigued, she learned about vogue history and culture on YouTube, and later went abroad to experience it herself. After learning the ropes, she contacted the legendary Haus of Mizrahi in the U.S. and was accepted as a member in 2009. In the time since, Koppi became a legendary house mother in her own right, held the first vogue ball in Asia and did her Japanese contemporaries proud along the way, including winning Grand Prizes for her performance at Vogue Nights, Candy World Rumble, and Latex Ball, among others. Koppi competes in multiple categories: Oldway, which harkens back to the beginnings of vogue in 1970s and emphasizes dip and spin techniques; and Vogue Femme, which has a notably different speed and flow, and utilizes techniques that have since been popularized on Drag Race, such as duckwalking, and what is commonly known these days as the death drop.

For would-be voguers in Tokyo, there are now numerous drag and ballroom houses to choose from, including legendary houses of Ninja, Xtravaganza and, of course, Mizrahi. Despite being nominally Japanese, some like Mizrahi, include non-Japanese among their ranks. Even among those not affiliated with a house—so-called 007s—there is a refreshing mix of experience, nationalities and sexualities.

One aspect of vogue culture that has changed in both the West and Japan is its embrace of inclusivity: competition categories based on self-identification. There are also categories such OTA (Open to All) where different groups can compete together. “When I started voguing, most performers were straight. At that time, the voguing community had little to do with anything LGBT; it was just thought of as a dance, like imitating Madonna. It was more like dance teams than drag houses,” Koppi says. “These days, we have more to do with the ballroom culture, such as having events in Ni-chome. There are more young would-be drag queens who are specifically interested in ballroom.”

In the future, Koppi, despite being a sought-after vogue teacher, wants the emphasis to be less on moves and technique, and more on bridging the culture gap, and bringing vogue together with the rest of the Japanese drag scene. “We appreciate that everyone loves and is interested in Drag Race-style drag, but it’s much different from ballroom. There should be more of a mutual knowledge and respect for each other.”

Though they may have carried on as best they could with less work and virtual shows, Japan’s queer performers are, for the first time in years, able to look toward the future. Despite Pepe’s professional success here, they are thinking of moving on from the familiar lights of Ni-chome and instead living and working in the film industry abroad while continuing their transition and personal journey. As for Mx Terious, while endeavouring to restart the king scene post-COVID, they also hope to finish their lesbian fantasy novel. Angelix had taken a hiatus from drag to continue voice-training and learning Latin dance, in order to refine her Latin lover king persona. She hopes that with the increasing popularity of drag, more people will choose to participate, not just as spectators, but as performers as well. “I think there is some discrimination with regards to that,” Angelix says. “Drag is something straight people, or anyone, can do.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra