From Milk’s Oscar campaign to homegrown hit I Killed My Mother, queer cinema has most certainly registered on the pop culture radar this past year.

And 2009 doesn’t seem to be an anomaly, as the recent commercial success of C.R.A.Z.Y., Capote, Transamerica and Brokeback Mountain has confirmed that queer films do indeed boast broad appeal. Hence the motive behind the upcoming Queer Film Classics, a seven-year book series published through Arsenal Pulp Press that will cover 21 influential films about and by queer people.

With Concordia University profs Thomas Waugh and (Xtra.ca contributor) Matthew Hays sharing editing duties, Queer Film Classics was inspired by and modelled after two parallel British Film Institute series: Film Classics and Modern Classics. Since the 1990s, the BFI has served up in-depth readings of close to 120 canonical titles in film history, delivering scholarly savvy in an accessible style. QFC aims to give the same treatment to 21 of queer cinema’s most vital works and will release these small monographs at the rate of three per year until 2015.

Waugh, who has been teaching queer cinema at Concordia for 21 years, has seen firsthand students’ growing appetite for the genre. “For a while it was in all modesty a one-person show,” Waugh tells Xtra.ca. “If I didn’t do it, no one was going to do it. But now, there’s a real momentum going and we fill up the course very quickly. It’s quite exciting.”

But a question still begs to be answered: why hadn’t such a project already seen the light of day?

“It’s a combination of the marketplace and, even though I don’t think there’s any overt homophobia in the film publishing industry, I think by default it sort of is off the radar,” says Waugh. “It’s hard to explain. For a while, I think there was a strong queer market in academic trade publishing, but I think it has quieted down a bit.”

Indeed, a few queer films had in the past been given the BFI book treatment, so those titles were excluded from consideration. The same applied to a certain Oscar-winning Ang Lee flick about closeted cowboys. “We did get a proposal for Brokeback Mountain,” says Matthew Hays. “Although we love Brokeback, there have already been several books about it, so we felt like we could urge that author to come back to us with a different film title.”

The resulting crop of QFC titles, made in eight different countries between 1950 and 2005, is diverse in more ways than one — think thematically, stylistically, geographically, as well as in sex and gender. “We wanted to make sure that it wouldn’t all be white gay men, that we had films with trans themes, lesbians, people of colour,” says Hays. “I think diversity really has to be paramount in thinking about this series.”

The lineup of titles to unspool between now and 2015 feature works by Chinese filmmaker Chen Kaige (Farewell my Concubine), Italian masters Visconti (Death in Venice) and Pasolini (Arabian Nights), Filipino helmer Ishmael Bernal (Manila by Night) and Belgian auteur Alain Berliner (Ma vie en rose), among others. That’s on top of the many Canadian titles included in the selection, with entries by Deepa Mehta (Fire), John Greyson (Zero Patience), Jean-Marc Vallée (C.R.A.Z.Y.), Patricia Rozema (I’ve Heard the Mermaids Singing), Frank Vitale (Montreal Main) and Lynn Fernie and Aerlyn Weissman (Forbidden Love: The Unashamed Stories of Lesbian Lives).

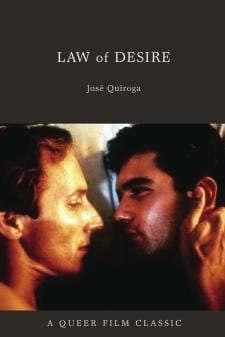

Over the next month, Arsenal Pulp will release the first three flagship volumes in the series, which delve into the Paul Morrissey and Andy Warhol collaboration Trash (1970), as well as Bill Condon’s Gods and Monsters (1998) and Pedro Almodóvar’s first overtly queer film Law of Desire (1987).

José Quiroga, the author of the musings on Law of Desire, remarks in the opening pages of his book that upon first viewing Almodóvar’s feature back in the 1980s, he was “most impressed by the fact that the characters in the film treat homosexuality as just one more element within a complex affective universe.”

What to make of queer cinema’s future now that such onscreen portrayals of queer people are increasingly common? Lately, that has been the million-dollar question for mainstream critics and pop culture writers who question the pertinence of queer film festivals and queer art more broadly speaking.

“The idea that we’ve become more accepted by the mainstream doesn’t deny that we have a very distinctive perspective on the world,” says Hays, “and I don’t think that gets lost, I think it’s enhanced through growing bodies of study and analysis around the queer gaze and what makes a film queer.” Hays also points to the recent collapse of the market for independent cinema as a sign that we’re headed into a queer renaissance, with a new output of fascinating work being done in the margins.

For more info on the Queer Film Classics, visit Arsenalpulp.com.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra