The first time I listened to Sufjan Stevens, I was fumbling around in a car with my first boyfriend. It was the winter of 2017 and we were 19, living with our respective parents in Ottawa and he wasn’t out to his family, so the only places we could hook up were in parking lots. We would sprawl and tangle across the back seat of his mom’s old station wagon. He was a sad, semi-closeted kid from the suburbs and so he’d loop downcast indie music while we made out and would get upset if I tried to change it to something upbeat. He had this pathetic playlist of six songs that he’d constantly play on repeat, and on that playlist resided two cuts from Stevens’s 2015 record, Carrie & Lowell: “Death With Dignity” and “Should Have Known Better,” the album’s first tracks. “Every road leads to an end,” Stevens would sing as we kissed. “Frightened by my feelings/ I only wanna be a relief,” he’d coo as we fought.

I began associating Stevens’s plucky guitars and hushed diction with the feelings I felt in the back of that station wagon: shame, discomfort and dissatisfaction chief among them. My boyfriend was cruel and controlling, desperate to rid himself of his sadness by forcing me to listen to depressing music while we had lousy sex. Looking back, I pity him. He was ashamed of himself, trapped somewhere he didn’t belong. He didn’t know what to do with his self-loathing so he divided it between me and Stevens. I broke up with him after a year, but I was left reeling for months afterward, overwhelmed by the feelings of worthlessness and anxiety that commonly accompany emotional abuse.

At some point during that relationship, I developed a nasty panic disorder. Throughout each day, my joints would stiffen, my heartbeat would quicken, my veins would bulge and my brain would burn. The panic attacks would come swiftly, without warning, at work, in class and always before sleep. I’d wake after long, fitful, sleepless nights for 6 a.m. shifts at the café I worked at and 8 a.m. university journalism classes, relying heavily on caffeine to get me through, which, of course, only worsened my anxiety. Even after I’d ridded myself of that boyfriend, the panic persisted.

Though my memories of Stevens were tinted by those awkward romps in the back seat, I decided after a few months that I ought to give him another chance. I am a Scorpio with a flair for melodrama, so I drew a bath and lit a candle, sunk low into the water and, for the first time, played Carrie & Lowell from top to bottom. As I waded deeper into the bath, into the album, into my own mind, I began, for the first time in a long time, to feel a sense of calm.

The arpeggiated guitars of “Death with Dignity” that had once haunted me now took on another meaning. As my therapist likes to tell me, anxiety is a fear response; the brain falsely believes it is in danger and so it fires up the amygdala in a desperate and futile attempt to save the life of its host. Carrie & Lowell’s spare and delicate opener deals directly with the thing that motivates and pulverizes us all—death—by coolly embracing it. Stevens sings of the fleetingness and finality of life atop a melody that winds upward, rising like a heart rate, like a life, before resolving. “We all know how this will end,” he sighs.

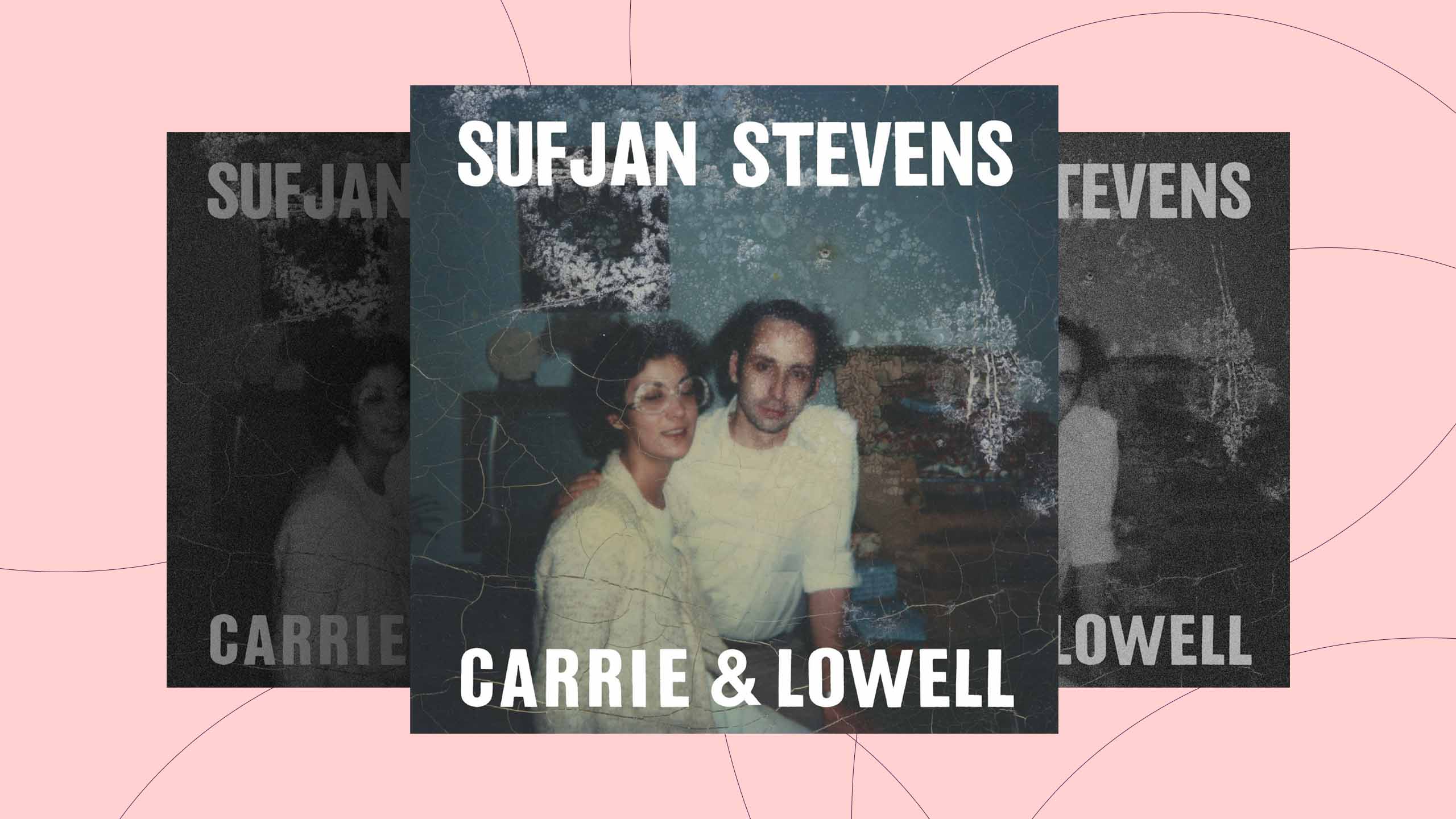

The titular Carrie is Stevens’s mother, who abandoned the singer as a child and died in 2012, a few years before the album’s release. “When I was three, three maybe four/ She left us at that video store,” he sings on “Should Have Known Better.” His album for her is ghostly and spare, the spectre of the mess she left behind permeating each pick of the guitar, each whispered poem. “I forgive you, Mother,” he confesses on “Death with Dignity,” signalling that even a ghost can be offered absolution; a sensible conclusion for a Christian like Stevens to draw.

Though he’s fixated on the sins of the past, Stevens posits that relief lies in what’s ahead. “Should Have Known Better” starts sad, but at its midpoint the sadness is suddenly punctured by a chipper synth that flips its lovelorn chords into something major and whole. “My brother had a daughter/ The beauty that she brings, illumination!” From death springs life; from pain comes ecstasy.

For a long time there was debate over Stevens’s sexuality, a decoding of his lyrics to determine whether or not he was gay. “All of Me Wants All of You” contains key evidence. He is both disappointed and obsessed with a lover. “In this light you look like Poseidon,” he exhales, invoking the massive and rippling god of the sea. His lover casts an enormous shadow; Stevens casts himself as invisible and meek and dead. “I’m just a ghost you walk right through.”

On “Drawn to the Blood,” he sings of being doubled over by love, of rising to his lover’s occasion only to be bowled over and bludgeoned by abandonment. “For my prayer has always been love/ What did I do to deserve this now?” He mourns his lost love, the weight of his grief is no less titanic than that induced by the loss of his mother. Hearing this for the first time moved something in me. I had never heard a man sing of devastating, obsessive love for another man before. I thought of my back-seat boyfriend, the first boy I thought I loved, and how I’d tortured myself for him. I thought of how I’d flattened myself in pursuit of love, of attention. I felt sad for what I’d done to myself. I felt understood.

Grief is the icy undercurrent of the album; it is most profoundly explored on its centrepiece track, “Fourth of July.” The song is an imagined dialogue between Sufjan and Carrie.

As himself: “What could I have said to raise you from the dead?/ Oh, could I be the sky on the Fourth of July?”

As Carrie: “Did you get enough love, my little dove?/ Why do you cry?/ And I’m sorry I left, but it was for the best.”

The song is both a supreme achievement and the most enduring song from the record. Stevens and Carrie’s interlocution is mesmerizing and gorgeous; Carrie’s regret and Stevens’s aimlessness are evident in each stunning stanza. The song ends with Carrie’s parting wisdom: “We’re all gonna die,” which Stevens repeats eight times, each utterance of that phrase taking on a new meaning. We’re all gonna die is terrifying, harrowing, painful, liberating, ecstatic. Above all, it is true. It is the only truth there is.

Stevens spends the back half of the record contemplating that truism. If death is inevitable, then why shouldn’t it be chosen, especially when life is so full of suffering and abandonment? In his most desperate hour, he cries out for his Lord. “Jesus I need you, be near me” he pleads on “John My Beloved.” But God did not commune with his son on the cross, and likewise, Stevens receives no divine relief from his agony. On “The Only Thing,” he contemplates self-harm and suicide; on the penultimate track, “No Shade In the Shadow of the Cross,” he sees “blood on that blade,” a sign he’s “falling apart.”

Back then, in my moments of abject panic, when my brain was aflame and I craved the bliss of sleep and it wouldn’t come, the pain and horror were so profound I sometimes entered that darkest of places, where slipping one’s skin seems the only solution. In these moments in the dead of night I would summon all my energy and place my phone beside my ear and play Carrie & Lowell all the way through. It was painful, so painful, and it split open my darkest thoughts like an oozing wound. But with the bleeding came catharsis, and with catharsis came clarity.

The final track on Carrie & Lowell is “Blue Bucket of Gold.” Atop plain piano chords, Sufjan begs for companionship, from God, from a friend, from a lover, from anyone. He pleads for someone to come and strip him of his misery. “Lord, touch me with lightning,” he prays, asking God to strike him with divinity as He did with St. Paul, who was converted instantaneously by a bolt from the sky.

God is silent at the album’s end. All of Stevens’s poetry and prayer have left him with nothing and nobody. For the album’s final two and a half minutes, a freezing synth billows out. It is a forlorn and funereal sound. After hours of sleeplessness, I would lie there alone and let that synth wash over me. I’d sink deep into the ether. I’d imagine what it would feel like to feel no panic, to suffer no pain, to exit my body and become one with that synth. My brain would darken. I’d slide into the void. And inevitably I’d find myself awake and rested, a new and brilliant day shining over me.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra