Norma Tanega bounced through life to the beat of her own drum. In 1966, she scored an international hit with the offbeat folk-pop single, “Walkin’ My Cat Named Dog.” That same year, Tanega moved to England and began a relationship with Dusty Springfield, writing songs for her and other artists, including Blossom Dearie. After these early successes, Tanega settled into a quiet life outside of the music industry, while continuing to work as an artist and educator. Decades later, her song “You’re Dead” was given new life as the theme of the comedic vampire film and TV series, What We Do In The Shadows. Sadly, just as Tanega’s music was receiving renewed interest, she passed away at age 80 in December 2019.

That could have been the end of Tanega’s story, but as a new series of retrospective projects proves, there’s a lot more to her radically inclusive politics and improvisatory spirit of creation. Tanega is best known for her 1966 debut album (also titled Walkin’ My Cat Named Dog), yet she recorded two others before the end of that era: the dazzling I Don’t Think it Will Hurt if You Smile, and the quiet acoustic collection, Snow Cycles (which remains unreleased). Songs from both rarely heard albums are included on the new Tanega compilation, I’m the Sky: Studio and Demo Recordings, 1964–1971. For longtime fans or curious newcomers, it’s a treasure trove.

“I always played for personal joy, and that could make things difficult. Music is for pleasure. I was never good at business,” Tanega is quoted in the liner notes from a series of contemporary interviews, one of which was conducted just 16 days before she passed away from colon cancer. “I never wanted to be a serious artist because I like to laugh too much.”

That laugh is present throughout Tanega’s life: curling up the corners of her mouth in early television appearances, as she counts out the 5/4 time signature in her instrumental “Clapham Junction,” or in scenes telling stories at the kitchen table—hair then turned white—in a 2011 short film. This spirit of freewheeling imagination dates all the way back to the lyrics of Tanega’s signature song: “Happy, sad, and crazy wonder/ Chokin’ up my mind with perpetual dreamin’.”

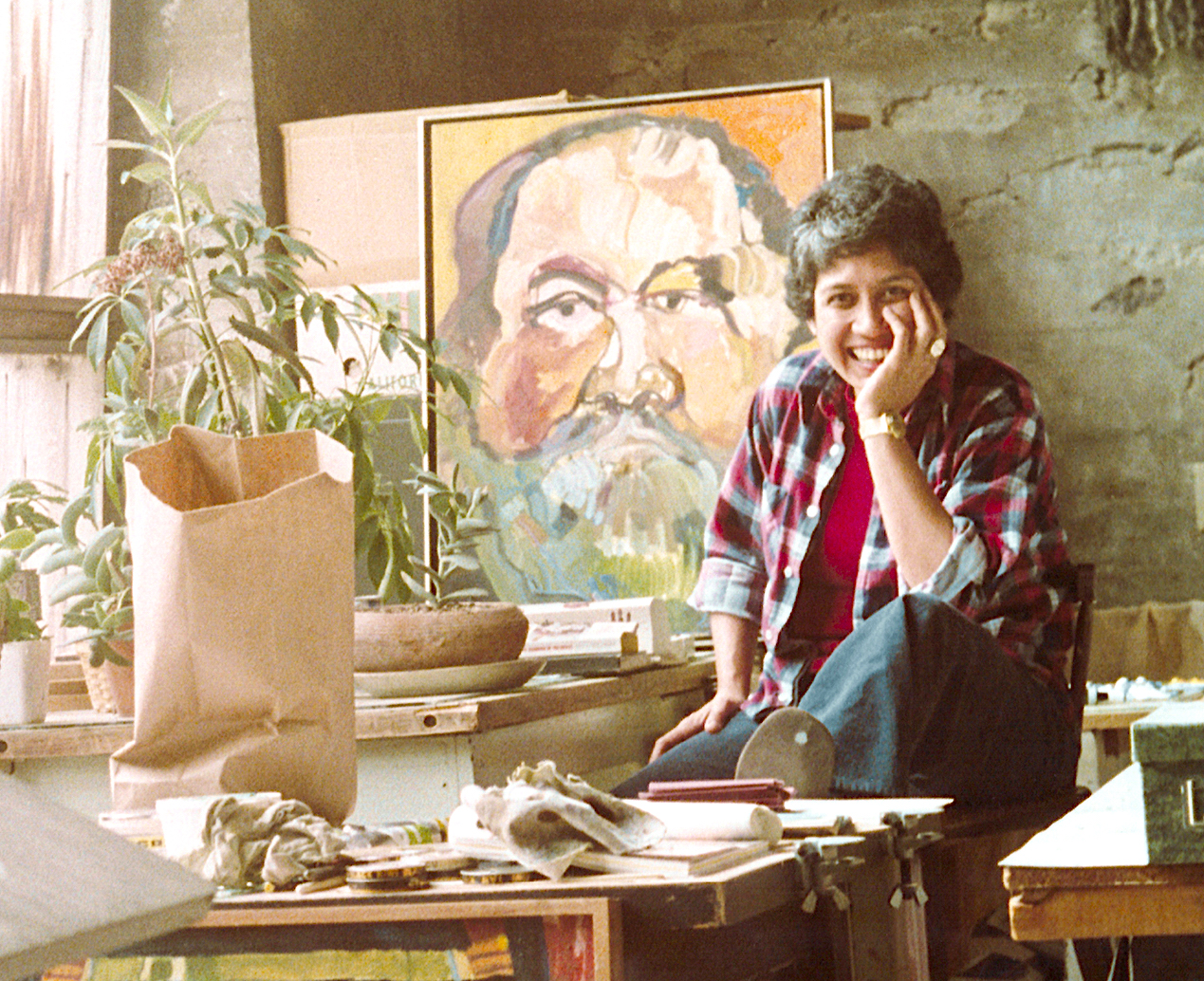

Born in 1939 to a Panamanian mother and a Filipino father, Tanega stood out as a queer woman of colour in the New York folk music scene, which was largely populated by straight, white faces. She was raised on the west coast, studying at Long Beach Polytechnic High School, and Scripps, the women’s liberal arts college in Claremont, California, a small city on the edge of Los Angeles, before boldly venturing to the Big Apple to become a musician. Visual artist Diane Divelbess—Tanega’s future romantic partner—first met her when they were both college students, and recalls her astonishment at this cross-country relocation.

“We all wished Norma well, even though we thought she was crazy,” Divelbess says in an interview with Xtra. “We admired her for taking off because it scared us to death. It’s the kind of thing that you do when you’re young and stupid. You think, ‘Oh, I’ll just go play my guitar and sing at some of the little places in Greenwich Village.’ It’s like the flower children from the Midwest who ended up in Haight-Ashbury in San Francisco. It was a wild time when people just moved.”

“I never wanted to be a serious artist because I like to laugh too much.”

Tanega arrived in New York in 1963, performing her songs in the Greenwich coffee-house scene and joining protests against the Vietnam War. It has frequently been written that she met producer Herb Bernstein, the man who kickstarted her music career, when Tanega worked as a camp counsellor in the Catskill Mountains. However, the 90-year-old industry veteran, who also scored hits for Lesley Gore, Laura Nyro and Dusty Springfield, is quick to correct this oft-reported mistake.

As Bernstein explains during a phone call with Xtra, he taught at Eastern District High School in Brooklyn while moonlighting as a producer and arranger. Bernstein’s recordings caught the ear of Bob Crewe, a fellow producer who earned a string of hits for Frankie Valli and the Four Seasons. These successes allowed Crewe to build his own studio, launching the labels Dynovoice and New Voice, and hiring Bernstein to work in-house. Crewe was portrayed as openly gay in the Four Seasons biopic Jersey Boys, though his brother told the New York Times in 2014 that Bob was discreet about his sexuality.

Credit: Courtesyof Corinna Müller

Two days after starting at the studio, Bernstein got a phone call from one of his students, persistently promoting her friend Norma. “She wouldn’t take no for an answer,” laughs Bernstein. He caved and invited Tanega to Crewe’s headquarters on 60th Street and Broadway. “The truth of the matter is that I really expected her to be there for 10 minutes, and that would be it. She started playing me these songs, and each one was weirder than the next. It was almost impossible to figure out her rhythms. I felt like I was going to school.”

Nonetheless, Bernstein heard potential in one of Tanega’s tunes, one based on her experience living in a New York apartment that did not allow dogs. To counter this, she adopted a cat named “Dog,” whom she proudly walked on a leash. Bernstein added a few Motown-inspired flourishes, and the song raced up the charts in the U.S. and U.K., hitting #3 in Canada.

“One day I was driving down the freeway,” Divelbess says. “I turned on the radio and heard her singing ‘Walkin’ My Cat Named Dog.’ I almost drove off the road.”

The lyrics of Tanega’s debut album emphasized her whimsical pursuit of personal freedoms. In the second verse of “A Street that Rhymes at Six A.M.,” she sings, “Syncopate your life and move against the grain/ Don’t you let them tell you that they’re all the same.” She uses sarcasm to powerful effect on “You’re Dead,” writing about her struggles in New York’s competitive music scene: “Don’t sing if you want to live long/ They have no use for your song.” Thankfully, the non-album single “Bread” found Tanega celebrating the spoils of early success: “It can take away the hungry look/ It can buy you anything in the book!”

The following decade was a whirlwind for Tanega. She performed on American Bandstand, and embarked on a North American tour as the only woman joining all-male folk acts such as Gene Pitney and Chad & Jeremy. In 1966, Tanega travelled to England and made several other TV appearances, meeting Dusty Springfield on the set of Thank Your Lucky Stars. “She was witty and flirty—how could you not love her?” Tanega told British journalist Penny Valentine at the time.

She returned to California in the early 1970s, followed by Springfield, who bought a house in West Hollywood. Divelbess (who got together with Tanega post-Springfield) recalls being dazzled by the stars who showed up at her parties. “One time Lily Tomlin was there, performing part of her one-woman show The Search for Signs of Intelligent Life in the Universe,” she says. “Another time at a costume party, Dusty dressed up as Marie Antoinette. Norma didn’t need a costume, because she was just Norma. She was comfortable everywhere.”

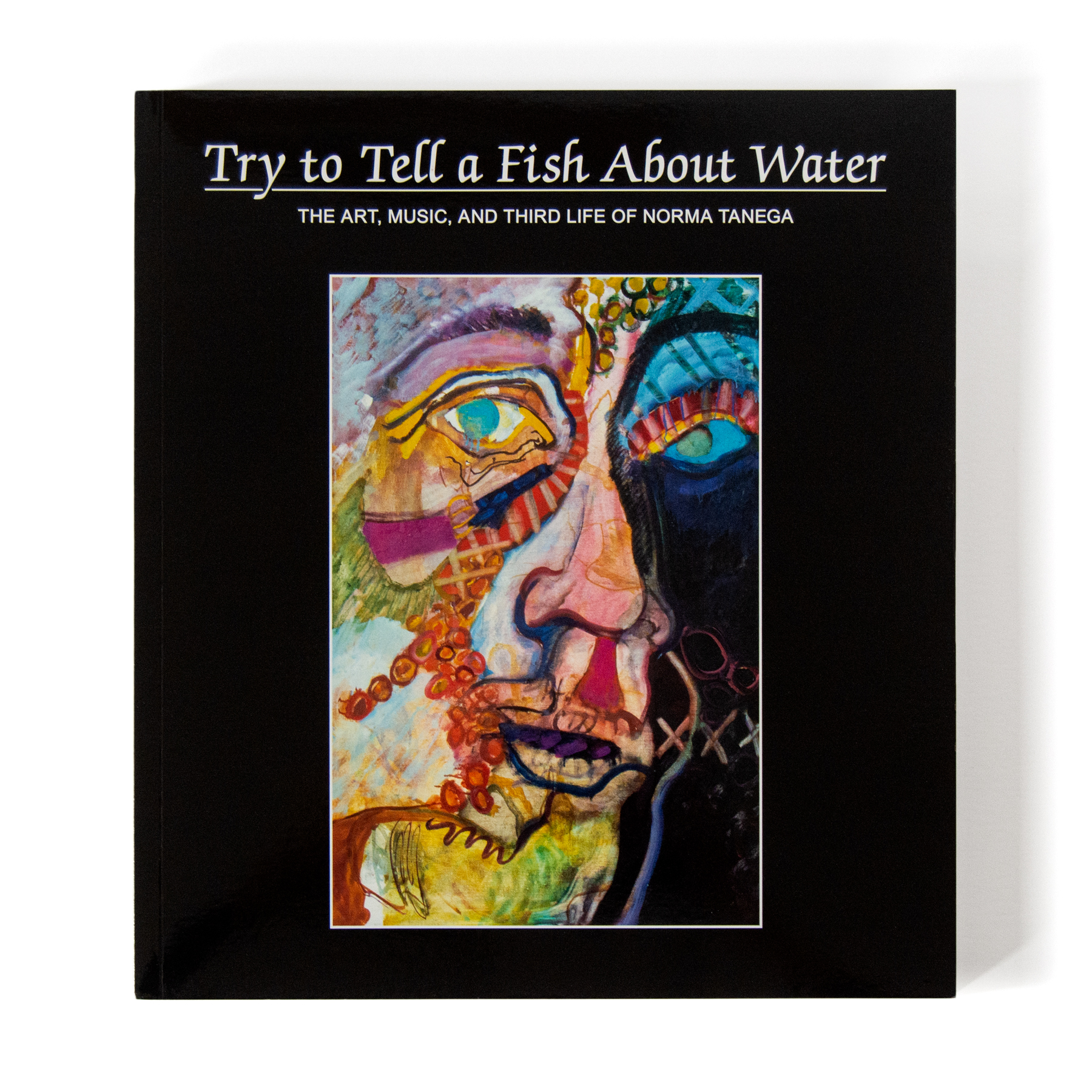

After her six-year relationship with Springfield ended, Tanega began working as a gallerist and emerged as a prolific painter. Her vibrantly colourful body of work—surrealist portraits, neon hockey masks and otherworldly landscapes—are showcased in the new biography, Try to Tell a Fish About Water. Tanega continued as a musician, yet switched her focus to percussion in a number of experimental groups such as HybridVigor and Brian Ransom’s Ceramic Ensemble. While an interest in unusual time signatures dates back to her 1960s folksinger era, these later projects freed her from traditional songwriting entirely.

Tanega found a familiar home in Claremont for the final four decades of her life, becoming a central figure in the city’s LGBTQ2S+ art community, recording music at the house where she lived with Divelbess, and teaching English as a second language. “She was excellent at that because she treated immigrants as who they were: doctors, lawyers, merchants, thieves, adults with interesting histories,” Divelbess says. “Norma taught them English from current events and topics of interest to adults, not something stupid like ‘Jack and Jill ran up the hill.’”

Credit: Courtesy of Anthology Editions

Reading through the pages of Try to Tell a Fish About Water, which is structured like an oral history with recollections from Tanega’s many friends and collaborators, it becomes clear that she touched countless lives. Her sense of humour is evident in cards sent to loved ones (“Have an urgent Christmas”), the business card for her “Tanega Toons” musical-instrument classes and other hand-drawn items from her personal archives.

“What still cracks me up is an invitation to a party the day before Father’s Day,” Divelbess says. “Out of nowhere it says, ‘And now for something completely different: a man with three buttocks!’ I have to read through that every time because it always makes me howl. That was just the way Norma did things.”

The 28 songs of I’m the Sky conclude with a collection of intimate, previously unreleased acoustic demos discovered in Tanega’s Claremont home. “Maggie My Dog” could be considered a sequel to her first hit, with equally self-aware lyrics: “She loves me when I’m sober/ And when I’m not.” On the hilarious standout “If I Only Had a Name Like Norma Tanega,” her rhyming punchlines are even more direct: “It can rise to the occasion/ Even though it’s not Caucasian.”

Bernstein tells me he’s overjoyed that these unheard songs are finally seeing the light of day, alongside the album that launched both his and Tanega’s musical careers.

“Making Norma’s first album was a labour of love,” Bernstein says. “I could see on her face that she didn’t like a few of my suggestions, but she tried them all anyway. Sometimes she was right. I remember recording the song ‘I’m the Sky’ with about 40 musicians, before we scrapped that. In the end, all you need is Norma and a guitar.”

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra