Hobin's Rest Your Heart.

Lullabies, fairy tales and nursery rhymes. That’s the usual fodder for the work of Ottawa-based photographer Jonathan Hobin, whose previous collections have explored the darker aspects of childhood and humanity, in part by depicting the lyrics of children’s lullabies in picture form.

The roots of his new project, Little Lady/Little Man, are no different. But the look of the collection and some of the themes are departures from his previous work. In this show, which features life-sized and larger-than-life portraits of his grandparents throughout their lives and up until their final days, gender and mortality are the focus.

“This is a bit of a divergence from what people are used to seeing from me,” Hobin says. “It’s more personal; it’s more photo-documentary, which is not something I personally gravitate toward. I would say it was a last-ditch attempt to hold on to a piece of [my grandparents].”

The new collection was inspired by two lullabies, “Little Lady Make Believe” and “Little Man, You’ve Had a Busy Day,” which Hobin’s grandfather used to sing to his children and grandchildren when they were little.

In 2002, when Hobin’s grandfather believed he was about to die, he secretly recorded the lullabies for posterity so his family would remember the songs that were central to their growing-up years and perhaps pass them on to their children.

When Hobin discovered the recordings, he was struck by the lyrics — and the notion that we never really grow out of the highly gendered roles of our youth.

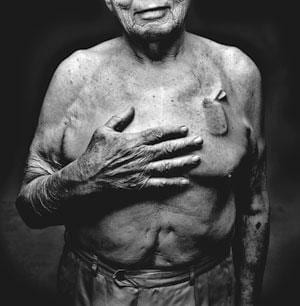

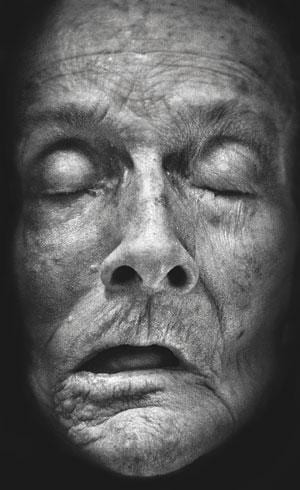

“The songs themselves became a metaphor for the path that we’ll all inevitably take as archetypes of male and female,” Hobin says. “This idea of aging and coming to terms with your own mortality, of our society putting emphasis on a woman’s physical beauty and a man’s physical strength. [The images show] a man, who comes from a very athletic family, dealing with loss of physical strength, and my grandmother, who was a real beauty, becoming virtually unrecognizable.”

Hobin embeds these idealized masculine and feminine qualities in his choices of media and scale. Some of the portraits of his grandfather are seven feet tall and printed on brushed metal. One of the portraits of his grandmother is mounted on a table, under glass. In the image, his grandmother is in her hospital bed, vulnerable and near death. The viewer can peer down at her, immortalized in those last few moments of her life. These images from her hospital room are sharply contrasted by carefree portraits that were taken by Yousuf Karsh at three different points in her life.

To make the exhibit all the more haunting, the recording of Hobin’s grandfather singing the lullabies plays on a loop from speakers in the exhibit space.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra