Born in Newcastle, Australia, McKenzie Wark built a highly successful career through the 1990s and 2000s as an academic in New York, where she still lives. She is known for her books A Hacker Manifesto (2004), Capital Is Dead: Is This Something Worse? (2019) and Molecular Red: A Theory of the Anthropocene (2015), that blend a Marxist analysis of capitalism and media theory to make sense of the modern world.

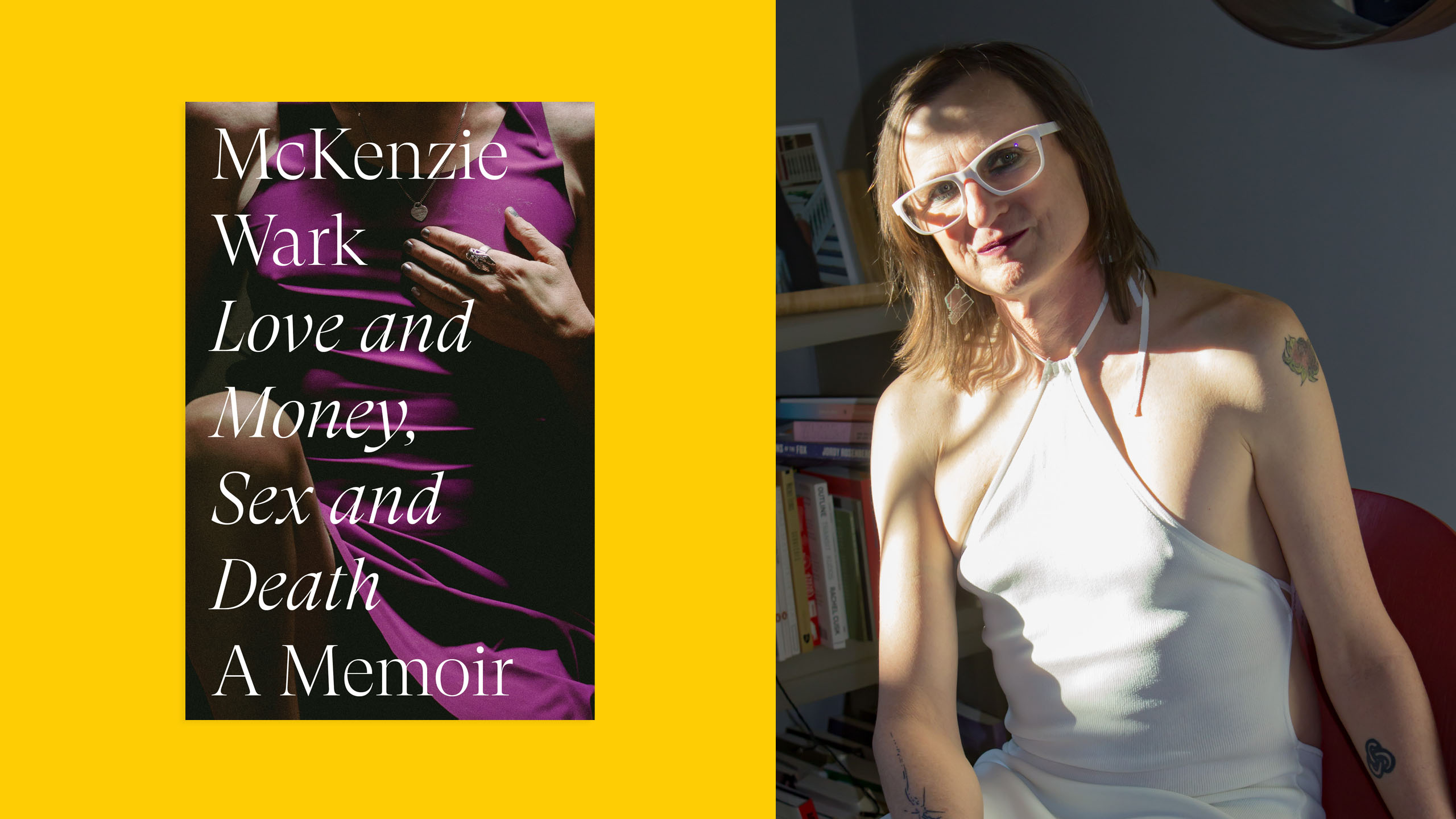

Wark, who is now 62, came out as a trans woman later in life. Her most recent book, Love and Money, Sex and Death (LMSD), is a memoir reflecting on her transition and her experience in trans communities as an older person. The book is written as a series of letters to significant people in her life divided into three sections: Mothers, Lovers and Others, and capped at the beginning and end with letters to her past self at ages 20 and 40.

This is Wark’s third book of autofiction in as many years, with Reverse Cowgirl, about Wark’s sexual history, out in 2020, and Raving, an autoethnography of her time in rave communities, out earlier in 2023. Of the three, LMSD is the most vulnerable. While many trans narratives centre around the process of coming out, or young adulthood, Wark spends little time on the details of her transition, instead emphasizing her relationships with others, her experience in trans communities and exploring how old memories take on new meaning over time.

I sat down with Wark over Zoom to discuss her new book.

Memoir can come with a lot of loaded expectations for trans people. What drew you to this genre?

There are a couple little hints in the text that I don’t quite think of it as that [genre]. It is structured as a series of letters to mothers, lovers and helpers. I’m interested in turning memoir inside out. So there’s McKenzie at three ages and each has an autonomous life in itself. The rest of the book is about the people who made me, the real people in my life who’ve shaped me. So it’s a memoir inside out, it’s the making of a life.

You have two other recent books of life-writing. Were you trying to capture something with LMSD that wasn’t in those books?

They are all books about certain practices or experiences: fucking, dancing and crying.

LMSD is the book about crying. I cried a lot when I wrote LMSD. The emotional range is a lot wider than Reverse Cowgirl. I wrote this one before I went on hormones because I felt like that would probably fuck up the writing process, and it really did—there were three years where I couldn’t do anything. So, I’m coming back to writing a little differently. I feel like the book produces the author rather than the other way around. Writing made me different, as did modifying the body that was involved in the process, because you write with the whole body. And it’s a different one, so the books are different.

The section “Others” is entirely written to other trans people, real, fictional and even mythological, as with the section written as a prayer to the goddess Cybele. What were you exploring about how you’ve been shaped by trans communities?

The three letters in that section are interested in a political language, an aesthetic language and a religious language. The political one was about Black Trans Lives Matter. It’s an ongoing thing, but there was a real moment in New York City where this movement really galvanized why we have to centre Black trans experience. So as a white trans woman, how do I position myself on the periphery of something like Black Lives Matter? How do you write from the periphery of something where you’re like, “I’m not important to it, but I can write about it.”

That chapter is written to a fictional version of a couple of younger trans people I knew who are no longer with us. I fictionalized that because those are not my stories to tell, but the structural phenomenon of anti-trans and racialized violence is a central story in trans lives. The burden ought not to fall only on Black writers to write Black life, even though acknowledging that has to be the centre of it. I think we all have a responsibility for addressing questions of race.

With the aesthetic one, I wanted to also capture a bit of the bitchy quality of intra transfemme conversation. That one is an argument about aesthetics that has this little subtext of “you fucked my ex, you bitch.” It’s got this other little thing going on underneath it to keep it real. That one is about middle-class trans women “ladies who lunch” trying to think through what the trans aesthetic is—aesthetics are gender to begin with, and then we add a little twist to it.

The one that was really a challenge to write as a third-generation atheist was the prayer to Cybele. For some trans people, a sort of spiritual dimension is very important. It wasn’t for me, but I am interested in that.

Cybele is the mother of all gods to the Romans in the Hellenistic world, but was treated as a foreign god in this complicated way. Her celebrants [the Galli], to use a completely anachronistic word for them, were trans women. And their religious practice, to use another anachronistic word, was basically rave: music, dance and the ecstatic.

A lot of trans people get kind of spiritual, but [there’s sometimes a question of] are you appropriating something that’s not really yours to have? The Galli and the cult of Cybele, which ran for over 600 years and was a significant rival to Christianity for a moment, feels like fair game to tease out and use as material for a language for dealing with what’s unknowable about life.

I was curious about the concept of Femmunism that you developed throughout the book.

I got the word Femmunism from a meme of someone holding up a sickle and a Hitachi Magic Wand. I was raised in a Marxist tradition, but always wanted a playful relation to that.

[The sickle] is the sickle of necessity—that everyone’s basic needs should be met—the basic proposition of communism. And then the [Hitachi] is for pleasure. What is pleasure in life? What are forms of social organization that would meet basic needs, and encourage the exploration of pleasures in life?

I think Femmunism is as good a word for that as any. It’s a sort of lean-in to revalue stereotypically feminine things. Can we think of the femme outside of its misogynistic casting? That interest in the interpersonal, and in presentation, and delight in surfaces, delight in indirect conversation—maybe those aren’t bad things!

There’s a whole history of women’s writing in French that this work is an almost parodic version of. A bit of Irigaray, and a bit of Cixous going on. So Femmunism is my word for that.

I was thinking about the two pairings of concepts that you have in the title; there’s love and money, which function as a pair, then sex and death. Each of them reveals something unexpected about each other.

In one section, you talk about an ex who would demand that people give her all their money, which you interpreted as a demand for love and revolution. What is the connection you are making here between money, love and revolution?

That’s a letter to Helen, who was someone I was in love with in my 20s. It was a relationship that ended badly, and that was my fault, and I was trying to come to terms with that.

Helen died young, too. She was a Chinese-Australian woman who would just say to people, “Give me your money!” And sometimes people did! But I think she was really saying, “Love me.” She was someone who was hard to love, but who really needed it.

Helen got me thinking about the relationship between those two things, and how one ends up displacing the other. I’ve had the title for this book for 25 years, I’ve tried to write it for a very, very long time.

The title consolidated very early: love and money are two ideas about relationships and the tension between those [relationships]. Then sex and death are events, like interruptions, one being permanent and the other one not.

Both are generative in different ways. The four terms of the title are paired in a very particular way and I’m trying to sort of tease out how those things thread together.

Chris Kraus once said that people write very frankly about sex these days, but not about money, so I wanted to explore that. As a sort of provincial, but middle-class petit bourgeois person—my father was an architect, he did fine—a small inheritance was to be expected. I didn’t want to pretend that it wasn’t there.

Death and family are also big themes in the section on mothers. Can you speak to that?

It sort of came to me out of this incident of finding a postcard that I’d forgotten I had that my mother wrote to me from the hospital when I was about six years old, shortly before she died of cancer.

It finally made sense why I write all the time: I’m answering my mother.

That unlocked the whole book, writing directly to my mother’s ghost, essentially. She didn’t live past her 40s. I’m 62, so she never even experienced this part of life, you know.

The first section is two letters to my mother, because it didn’t all fit in one. Then it’s rounded out with a letter to my sister, who had a very big hand in raising me. I have an older brother and sister, so I was raised by teenagers, which is very obvious to most people who know me.

I wanted to centre my sister as the person who had to take the place of my mother, whether she wanted to or not. She was 16, 17 years old, dragging this little kid around town. I even went on her dates.

That was my view of the grown-up world: my eldest sister. I owe so much to her, I’m getting teary thinking about it.

The first part also separates out mother from mothering. And the whole book is really about how we think about mothering as something that can be a distributed kind of care.

I’m skeptical that this whole nuclear family thing was ever a good idea, even as somebody who has kids in Queens [New York] with a co-parent. But mothering itself is this hugely important thing, and not least for trans women, because we mother each other as well—although I like to think of myself as a great aunt, rather than a mother, to other trans people. It’s a different relationship.

The idea of mothers versus mothering made me think of something you say in the first section of the book about finding mentorship difficult. Mentorship and mothering show up together throughout the book and in how you talk about having been made by other people in your life. What is difficult about mentoring for you?

Losing a parent young will really interrupt your sense of the reliability of care. A lot of people who lose parents—or who had parents who couldn’t parent—will report having to learn to self-manage, to become more autonomous before you’re supposed to.

That made it hard for me to accept mentors, and probably hurt me in academia because it’s all about patrons. In every sense of the word, I will not be patronized.

I went it alone a lot. To be very clear, people helped me, without me asking them to. I’m only here because other people were making things possible for me in ways that I found hard to accept. The book has got a lot of being shaped and also limited by others in different ways.

You write about looking to trans friends who are in a younger generation than you as inspiration. What do you hope that a younger generation of trans people will get out of reading your book?

A lot of visible older trans women didn’t make it into their 60s. There were so many obstacles to life, particularly the HIV/AIDS epidemic on top of everything else. I know other trans women who are around my age and we have connections, but we often have quite different tastes.

In terms of who raised me into trans womanhood, it was millennials, so I’ve absorbed a relation to the issues of a sort of millennial generation of people, who improved on a few things compared to the language and style of previous eras. Things started to get a little better. I feel like my readership is people who are 40 down to 20 because I teach people in their 20s. How you take certain habits from one time and translate them into the habits and thoughts of another time is often through teaching, you know?

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why you can trust Xtra

Why you can trust Xtra